‘Western DC’: a New U.S. Capital on the Ohio River

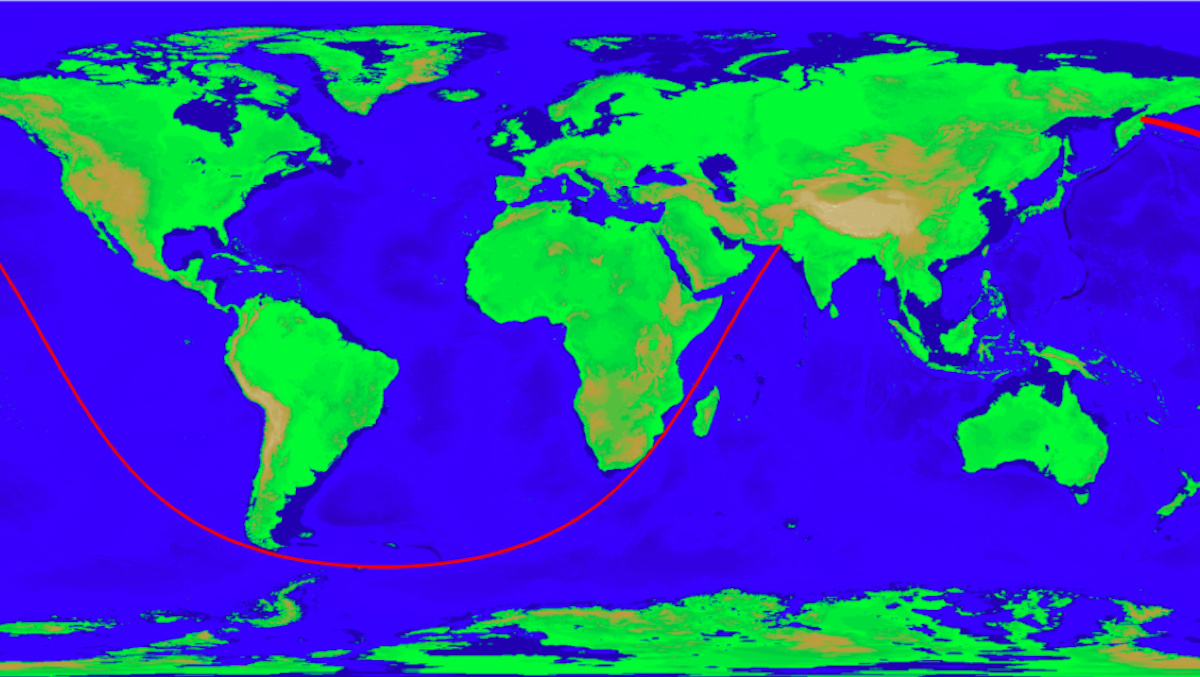

Does a central government need to be literally, geographically central? Of course not. In fact, when considered against the territory they govern, the location of many (if not most) national capitals is remarkably eccentric. One of the clearest examples is Moscow, 7 time zones and close to 4,000 miles (almost 6,500 km) west of Russia’s Far Eastern hub of Vladivostok, but less than 260 miles (about 420 km) east of the border with Belarus. Or take the UK: London is closer to Paris than to Newcastle, and Shetland, the UK’s northernmost archipelago, is closer to Norway’s capital than to its own (1).

But on the other hand, some capitals are remarkably central. Take Rome, almost exactly halfway down the boot of Italy. Or Mexico City, not that far from the country’s actual geographical centre (2). Why are so many capitals so noticeably non-central, while others so obviously are? Historically, geographically (and very generally) speaking, two opposing forces are at work in determining whether capitals are central.

The most basic principle is that of radiance. Imagine a powerful city gradually and radially extending its power over the surrounding area. The borders of the resulting nation would be fairly equidistant from the governing centre.

But that principle ignores a basic aspect of physical and human geography – its irregularity. Navigable rivers and inhospitable deserts, impassable mountain ranges and fertile plains all influence the expandability of any empire. The fundamental influence of this irregularity constitutes the second principle, which to a large extent can be reduced to what might be called portuarity (3).

Access to the sea is conducive to commerce and communication, giving port cities a head start in empire-building. Hence the seaside location of many capital cities – a location which obviously also limits their territorial expansion to the non-watery half of their surroundings.

But there may be another factor at work. The powers that be may choose to move the seat of government from one place to another, usually to a more central location. The practical and/or symbolic reasons cited for the move actually serve the same purpose: to strengthen the unity of the country. Planned capitals include:

Probably the most famous – and certainly the most successful – example of a planned capital is Washington DC, a federal district built on the left bank of the Potomac to house the capital of the United States of America. That privilege had passed between New York City, Philadelphia and even Trenton before the District of Columbia was agreed upon as a compromise between south and north.

That choice was not just politically expedient, it was also demographically fortuitous. As shown by a map of the mean centre of America’s population (discussed in #389), DC was built quite close to the US’s demographic centre of gravity as it was then.

But already in 1800, that centre had started its long, westward drift. If the location of America’s capital was a compromise, in between the North and the South of the Original Thirteen States, wouldn’t it make sense to move it west when the country expanded in that direction?

Exactly that was proposed in 1850 – a mere half century after the inauguration of DC as the nation’s capital. By that time, America’s centre of demographic gravity had moved to the western reaches of present-day West Virginia.

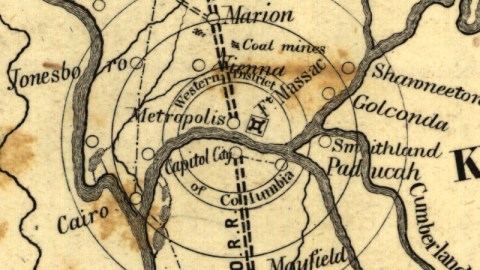

This map, drawn up by a William McBean, projector, identifies a circular area on both the Kentucky and Illinois banks of the Ohio river, not far from its confluence with the Mississippi at Cairo, as a so-called Western District of Columbia. The legend of the map “of a part of the SOUTHERN & WESTERN STATES” (4) mentions historic Fort Massac, which would probably have been the centre of the mentioned “WESTERN ARMORY” and places it next to the city of Metropolis, across the river from Capitol City. Those names sounded sufficiently grand for what was judged (or gambled) to be “the probable future site for the seat of Government of the UNITED STATES or Western District of Columbia etc.”

Excerpt of the aforementioned map; for entire map, see here at the Library of Congress.

Very little information is available on the nature of the aforementioned Western Armory, its relation to the Western District of Columbia , or for that matter the Eastern one. Does the existence of two DCs imply dual capitals, and would these have been alternating or would they each have co-managed a part of the vast territory?

It’s difficult to determine how serious this area’s bid for the location of a Western DC was. Present-day local maps show no settlement where Capitol City is located on this map, on the Kentucky bank of the Ohio river. Today, there are only two Capitol Cities in the US: as generic definition of the actual capital, Washington DC, or of the generic capital city of the unnamed state that’s home to Homer and the other Simpsons from the eponymous tv series (5).

Was this Capitol City an ephemera, a city the existence of which was postulated on paper, thus to will it into being? If the same thing was attempted with Metropolis, on the Illinois side of the river, at least it worked in that latter case. Metropolis, Greek for the Mother City, is a sleepy little All-American town that in no way resembles a busy metropolis. No US Congress has ever convened here. And no US president was ever resident here.

However, the town’s name links it to another strand of American history – comic book history. Metropolis is the name of the fictional city where Clark Kent/Superman forges a career as both a journalist and a superhero. Ironically, Metropolis, Illinois more resembles the Smallville where Clark Kent grew up.

This has not prevented the town to capitalise on its connection to the caped superhero. Metropolis has been declared “Hometown of Superman” by both DC Comics and by the Illinois State Legislature. It houses a Superman Museum, hosts an annual Superman Celebration, and its town centre is the location of a huge Superman statue.

In early January 2009, president-elect Barack Obama visited Metropolis and had his picture taken with Superman.

Many thanks to Arthur Howe for sending in this map.

Strange Maps #492

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

(1) We could go on with examples aplenty, but the question of precision arises: which is the world’s most eccentric capital (geographically speaking, of course)? Does anyone have a list? I’m guessing such a list would involve calculations taking in the size of each country, and the distance from their geographical centres to their capital cities. Complex stuff. If I’d have to put my money on any capital, it’d be Kinshasa

(2) Whichever centre of Mexico you pick. Methods of measurement vary, as do definitions as to what to include, leading to various claims from a handful of localities, none of them very far from Mexico City though: the city of Tequisquiapan in the state of Querétaro; the Cerro del Cubilete, a mountain in Guanajuato state; two points in Zacatecas state, one of which is the village of Cañitas de Felipe Pescador; and the town of Aguascalientes in the eponymous state.

(3) Or the predominance of the maritime capital, if you’re not into the whole brevity thing.

(4) At the time of publication, only Iowa, Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas and, most recently, California had achieved statehood west of the Mississippi. Hence the designation of the area described as ‘western’ instead of ‘midwestern’.

(5) The Simpsons are keen fans of curious cartography, and maybe even of Strange Maps. Map #459, of Marge Simpson’s European Adventure, shows the diva of Springfield filling out a map of Europe with her remarkable profile. That map was sent in by Micky Hulse (original context here), and the Simpsons reference seems to have come full circle. Many thanks to commenter Jack Hinks for sending in a screengrab from a recent Simpsons episode (cf. inf.)