White Noise: Pousette-Dart and Ryman at The Phillips Collection

This summer at The Phillips Collection there’s a different kind of colorblindness going on. White is the “new black,” or at least the color telling the most interesting stories in Pousette-Dart: Predominantly White Paintings and Robert Ryman: Variations and Improvisations, both of which run through September 12, 2010. Richard Pousette-Dart and Robert Ryman share not only an affinity for using white to express larger ideas, but also a love of music—Pousette-Dart being the son of a musician and father of musicians, which Ryman himself played jazz before turning to painting. Their white works represent a different kind of “white noise,” namely that of minimalist, abstract, nonnarrative, nonillustionist art that clears away all peripheral cacophony and allows us to hear ourselves think about painting and about the world.

The classic origin myth of Ryman’s career is that he came to New York City in 1952 as a jazz saxophonist, got a job as a guard at the Museum of Modern Art, and became a painter after prolonged exposure to Cezanne, Matisse, Picasso, Rothko, and others. “The first time I saw Rothko,” Ryman explained in an interview earlier this year, “I didn’t know what to make of it because I had been looking at Matisse. Rothko’s paintings were not pictures of things, or images of something, and that was the most interesting thing about them. I was not taken by the color so much, but by the way they worked on the wall and how they came out into the space; how they had presence, independently of what they represented.” Ryman doesn’t consider himself an abstract artist, but as a realist who works within abstraction to get at the reality of how a painting works, much as Rothko used abstraction to speak about emotional reality in a way that pure rational representation couldn’t. The paintings in this exhibition range from the late 1950s to today. Rather than a survey or retrospective, however, Variations and Improvisations aspires to the quality of jazz music, specifically variations centering on a central theme, in this case the use of white. “Painting is about the visual,” Ryman once said, “the meaning of painting is painting.” Ryman’s paintings may seem to be visual syllogisms—paintings that mean only painting itself—but how they circle around that idea continues to fascinate like a well-worn music album.

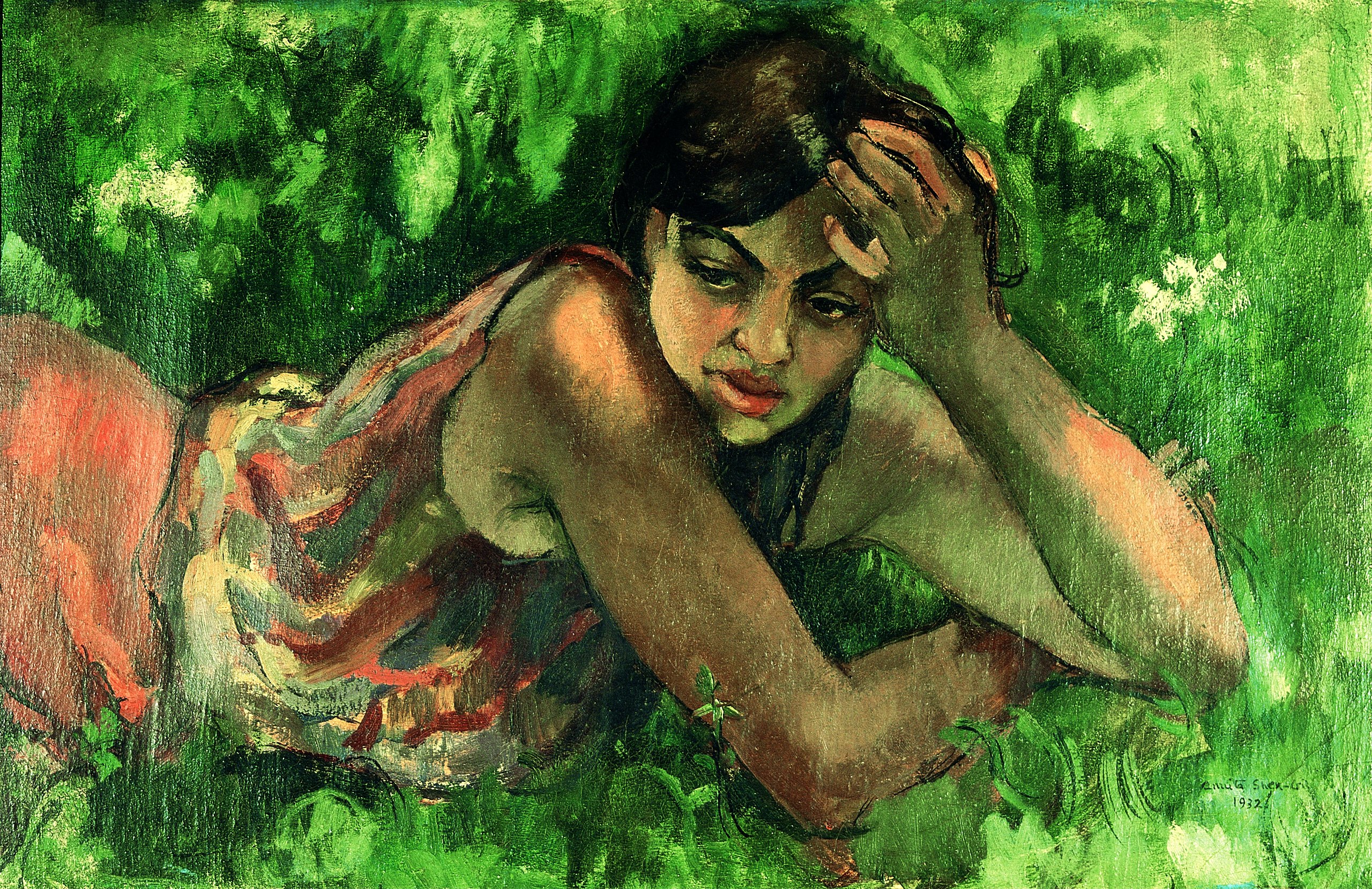

Whereas Ryman made and continues to make his name in white, Pousette-Dart worked in color for much of his career. Predominantly White Paintings focuses on paintings Pousette-Dart painted during the early 1950s in what might be called his “white period.” In 1955, Betty Parsons Gallery in New York City exhibited these white works, mostly drawn on canvas with graphite and colored with white oil paint and sparse splashes of other colors, together in a show titled Predominantly White: Richard Pousette-Dart Paintings. This exhibition recreates (and reiterates the title of) the 1955 show by reuniting some of those white paintings for the first time in more than 50 years. Like Ryman, Pousette-Dart ruminates on the use of white, but he expands beyond just a pure visual interest—of the paintings as paintings. Pousette-Dart mulls the symbolism of whiteness like Melville in Moby-Dick. In that sense, he touches on the cosmic nature of Rothko’s best work. Pousette-Dart’s 1950-1951 White Cosmos (shown) also aspires to music, but not that of improvisational jazz, but rather that of the most ambitious classical work. The notes to the show mention Pousette-Dart’s love of the music of Olivier Messiaen. White Cosmos and other works seem like the perfect backdrop for Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time. These white works seem like visions of the end of time, a roadmap to final destinations. “I strive to express the spiritual nature of the universe,” Pousette-Dart explained before his death in 1992. “Painting, for me, is a dynamic balance and wholeness of life; it is mysterious and transcending, yet solid and real.”

If Ryman’s art circles around the idea in endless variations, Pousette-Dart’s art aims at getting beyond the surface of the idea to transcend the limitations of our understanding. The Phillips Collection combines these two contrasting artists beautifully, bringing out the strengths of each all within the world of a single, colorless color. The volume behind this duo’s “white noise” deafens with the depth of its power and the breadth of its approach to a single theme. Working with little, they do much. You’ll never think of white as “just” white again.

[Image: Richard Pousette-Dart .White Cosmos, 1950-51. Oil and graphite on board, 36 x 48 in. Courtesy of Knoedler Gallery. © 2010 Estate of Richard Pousette-Dart / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.]

[Many thanks to The Phillips Collection for providing me with press materials for and the image above from Pousette-Dart: Predominantly White Paintings and Robert Ryman: Variations and Improvisations, both of which run through September 12, 2010.]