Why the Mona Lisa Can’t (Won’t?) Go Home Again

People who can name only one painting in the world usually name the Mona Lisa. For better or worse, Leonardo da Vinci’s portrait of (probably) Lisa del Giocondo rises above all cultural barriers and transcends taste with a smile. As Donald Sassoon argued in his 2001 book Becoming Mona Lisa: The Making of a Global Icon, a large part of that fame came from the infamous theft of the painting in 1911, when Vincenzo Peruggia walked out of the Louvre with the work hidden under his coat and fled to his homeland of Italy, which Peruggia believed to be the painting’s homeland, too. After waiting two years, Peruggia tried to sell the painting to the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. After Peruggia’s arrest, the Mona Lisa toured her homeland one last time before heading back to the Louvre. With the 100th anniversary of that theft looming this August, the Uffizi and Italy want La Gioconda (the Italian nickname) back, at least for a while, but the Louvre and France say La Joconde (the French nickname) is going nowhere.

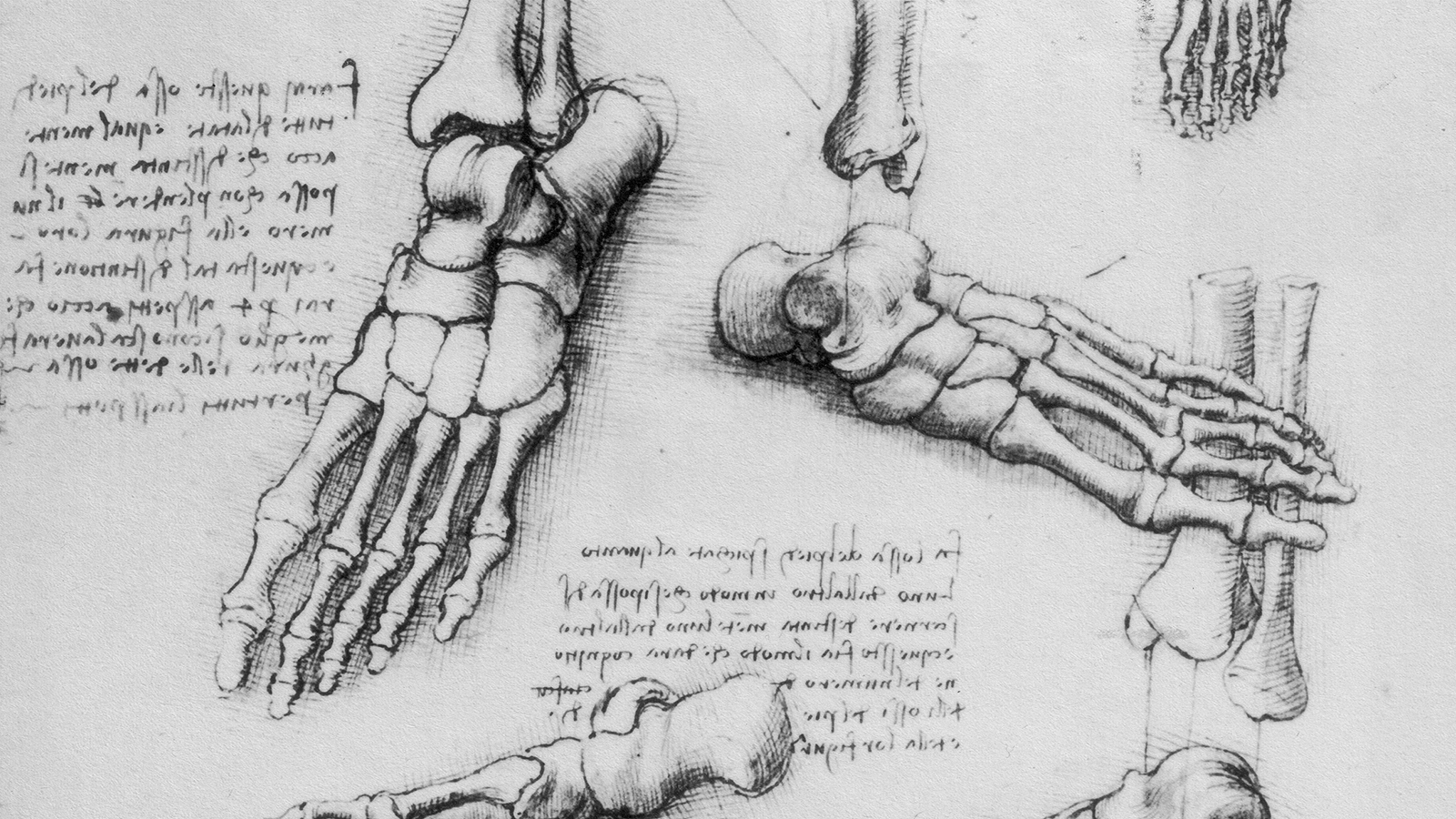

The national battle for Mona Lisa is a centuries’ long one. da Vinci began the painting in 1503 or 1504 in Florence, but only finished it on French soil after moving there in 1516 on the invitation of François I. After Leonardo’s death in 1519, the French king purchased the painting from the family of da Vinci’s assistant, who inherited what his master left behind. Mona Lisa thus entered the French royal collection, where it stayed until the French Revolution, among other things, transformed the royal collection in the Louvre palace into the national collection in the Louvre museum. Since that transformation, fragile little Lisa’s left home only three times—against her will in 1911 and through loans to America in 1963 and to Russia and Japan in 1974. Armed with 100,000 signatures from Italians, Italy’s cultural leaders hope to change that three to a four, but the Louvre says that the fragility of the nearly 500-year-old painting is too great to risk any travel.

Of course, the Louvre’s said that before. As Margaret Leslie Davis recounted in her mesmerizing Mona Lisa in Camelot: How Jacqueline Kennedy and Da Vinci’s Masterpiece Charmed and Captivated a Nation (which I reviewed here), then First Lady Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy worked her magic on then French Minister of Culture Andre Malraux to finagle a trip to Washington, D.C., and New York City in 1963. The American diplomat assigned to personally ensure the safety of the painting developed health problems from the stress of protecting the masterpiece from the slightest change in temperature or humidity, but the American tour—a Cold War cultural coup—otherwise was an unqualified success. A little over a decade later, France balanced out the Cold War loans by sending the painting to Russia, where it toured with no incidents, something which couldn’t be said of the final Tokyo leg of the trip. A handicapped woman angered by the Tokyo National Museum’s accessibility policies sprayed red paint at the painting. The Louvre’s faced vandals targeting the Mona Lisa many times over the years, but that overseas scare may have frightened them from loans, even nearly four decades later.

Italy also presents a problem in their pseudo-serious claims to own the painting, at least in terms of heritage. The thief Peruggia received a mere 6 months of jail time—almost a reward for bringing the painting back to Italy. “Plan B” if the scheme to get the painting back in Italy for the anniversary of the theft seems to be a different kind of theft—grave robbing. Italian cultural organizations now believe that they are close to finding the grave of the woman who sat for the Mona Lisa. If you can’t have the “real thing,” it seems, they’ll settle for the real woman, if you subscribe to the idea that Lisa del Giocondo’s the woman with the million(s)-dollar smile. I can’t help but think that the Louvre worries that there could be some kind of legal battle over the painting once it is out of the country, especially in the current climate of art repatriation where even “sure things” aren’t sure anymore. A legal battle for the Mona Lisa would be fascinating to watch, but it would also definitely discontinue the practice of international art loans for a long, long time.

Ownership and conservation are the twin towers of the Louvre and France’s denial of the request, but the real reason is money. The Louvre draws tourism by the ton, and most of those tourists want to see the Mona Lisa. Judging from the throngs racing past the time I visited, many go only to see that painting, even at the cost of racing past millennia of masterpieces to get a good place in line for that moment with Mona. The Louvre simply can’t afford to part with La Joconde.