Biology Over Art: What Modernism Misses

Sometime in 1952, the American experimental musician John Cage put the finishing touches on a composition that challenged the definition of music. It was a three-part movement written for any instrument or combination of instruments. He called it four minutes and thirty-three seconds (4:33) and debutedit at Maverick Concert Hall in Woodstock, New York. David Tudor, an experimental pianist, performed it on the piano.

When Tudor walked onto the stage at Maverick Concert Hall he sat down at the piano, opened the score and sat in total silence for four minutes and thirty-three seconds. When it was over, he left the stage. Tudor’s performance was flawless.

4:33 became one of the most studied and scrutinized pieces of music in the 20th century because Cage left the score blank; the job of the performer was to remain silent for four minutes and thirty-three seconds. I learned about Cage and his soundless composition from a music teacher in college. Cage initially struck me as one of those avant-garde types that only obscure art critics studied, but we performed 4:33 in a music theory class and I was immediately drawn in, seeing it as something more than nothing. Does silence count as music? What is music?

Cage was partially inspired by an American painter and graphic artist named Robert Rauschenberg who in 1951 created “White Paintings,” which were nothing more than a series of blank white canvas. For Rauschenberg, the paintings were the lighting and shadows of the room – the tiny atmospheric nuances that left the canvas not entirely white. For Cage, 4:33 was the murmuring of the audience or the natural ambience of Maverick Hall. It was a reminder that total silence is impossible.

By afflicting what is comfortable for the audience, Cage and Rauschenberg joined other modern artists who made careers by challenging our aesthetic preferences. For these so-called modernists, art was about rejecting traditions and pushing aesthetic boundaries to the limit. In The Blank Slate, Steven Pinker mentions the art critic Clive Bell, who went as far as to suggest that, “beauty had no place in good art because it was rooted in crass experiences” and abstract painter Barnett Newman, who declared that “the impulse of modern art was ‘the desire to destroy beauty.”

The philosopher Denis Dutton sums up the modernist doctrine in his book The Art Instinct:

Promoters of modernism cited Dadaist experiments to insist that beauty could reside in any perceptual object, that people could be “taught” to take aesthetic pleasure in any experience whatsoever. Once this fact was understood, so modernist hopes went, we would all become free to enjoy pure abstraction in painting, atonality in music, random word-order poetry, Finnegans Wake, and readymades, just as much as we enjoy Ingres, Mozart, or Jane Austen. “Difficult” modernist art, literature, and music could become popular – culturally dominant, in fact – given enough time and familiarity. As Anton Webern longingly imagined, the postman on his rounds might someday be overheard whistling an atonal tune.

For modernists, human nature is a blank slate. And with enough exposure we can enjoy anything – a silent piece of music or a blank canvas. Our ability to appreciate new kinds of art sees no limits.

The problem with this perspective is that it gets human nature wrong. We aren’t blank slates; our aesthetic preferences evolved just like our craving for salty foods and sex. As Dutton explains, “human nature… sets limits on what culture and the arts can accomplish with the human personality and its tastes. Contingent facts about human nature ensure not only that some things in arts will be difficult to appreciate but that appreciation of them may be impossible.” Take that, blank slaters!

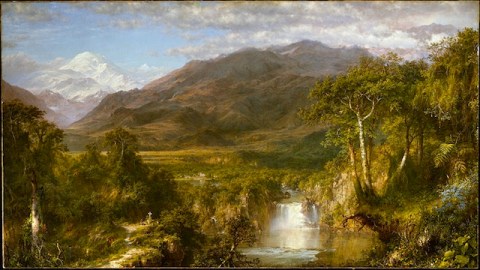

Consider visual art. People all around the world prefer paintings that depict wide-open landscapes including fertile land, diversity of greenery, evidence of animal and bird life and a body of water from a high vantage point. Does culture explain this uniformity? Or do our visual preferences relate to the African savannas our hunter-gatherer ancestors evolved in? Dutton goes with the later, stating that humans share an innate preference for African savanna-type landscapes in visual art because they are “not only the probable scene of a significant portion of human evolution, they are to an extent the habitat meat-eating hominids evolved for.”

If our appreciation of art has biological limits then why do modernists and the rest of those avant-garde types insist on transcending them instead of embracing them? A silent piece of music, a blank canvas… seriously?

A recent TED talk by experimental musician Mark Applebaum might explain why some gravitate towards the poles of our evolved aesthetic preferences. Applebaum’s Cage-esque projects include composing a score for three conductors to conduct but no musicians to preform, turning a wristwatch into a musical score and having an orchestra play gibberish while a florist garnishes a floral arrangement. Applebaum isn’t motivated to discover or reinvent music and he doesn’t come across as pretentious or critical of the mainstream. He’s inspired by whatever stimulates him. “Is it music? … This is not the important question,” he says. “The important question is: Is it interesting?”

Applebaum is driven by the same thing every other artist is driven by: novelty. We humans get used to songs, stories and paintings quickly. The Billboard top ten, New York Times bestseller lists, and MoMa galleries are in flux; mainstays are rare. The job of the artist is to introduce something new. But 4:33, “White Paintings” and wristwatches? The difference with Cage, Rauschenberg and Applebaum is they take it to an extreme.

Good art, then, finds a balance between these two perspectives. 4:33 and “White Paintings” are too novel and ignore innate preferences. On the other hand, artists like Bach or the Beatles embrace our evolutionary preferences – they introduced new and more complex sounds while maintaining some familiarity. With enough exposure, listeners adjusted and eventually appreciated the new sounds. We still return to them because there is something new with every listen; it takes many repeats for overabundance to downgrade its value.[1] The same is true of visual art – Mona Lisa – and literature – Hamlet.

Does this mean Cage is doomed for irrelevance? 22nd century art critics will probably still be riffing on 4:33. I’ll go back to my pre-college days and appreciate it for what it is: nothing.

[1] Bits of this paragraph is from a previous article I wrote.

Here’s an article by Adam Kirsch at TNR for further reading

Image via Wikipedia Commons