Exploring the Most Enigmatic Line in American Literature

Melville is so profound. That’s not to say that he offers easy solutions. In fact, the more profound Melville gets, the more elusive the solutions he arrives at. In a story called Bartleby, the Scrivener, A Story of Wall Street, Melville gives us a portrait of a copyist – a thin, efficient, anonymous figure named Bartleby, who is in a sense a human photocopy machine. And in this story, Melville follows the benign, kindly reflections of an employer. An employer of a man who at a certain point decides he just doesn’t want to be a copy machine any more. But he can’t protest because he’s actually become too traumatized and frozen by what life has brought him so far.

And so he becomes instead a fixture in the office, a burden, a constant moral reminder of all that’s wrong in the world, a symbol of a world turning people into human copy machines. The narrator of this story does everything any of us would do, and more, to try to solve the problem of this man he has employed who will no longer work. He’s just a burden on the payroll. What would you do if someone you fired wouldn’t leave?

Melville tells the horrible, horrible story of a guy who’s laid off and is told to collect his belongings and leave. And he won’t leave. He’s there the next morning. In fact, he not only won’t leave his job; he won’t leave the office, and he begins to live there.

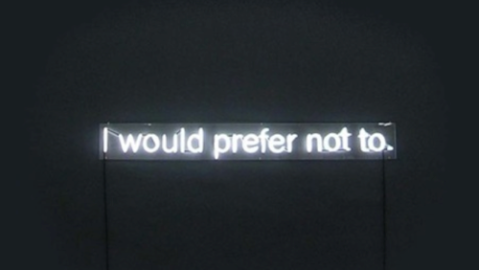

And Bartleby doesn’t say, “I will not leave,” he says, “I prefer not to.”

Now that “I prefer not to” is one of the most mysterious and enigmatic sentences in American literature because just what it means to say, is not “I won’t do it, try to make me do it,” but I “prefer not to.” Really, that’s a sentence that really does ask questions about coercion in the work environment and how important it is, how much we cherish that code of manners and courtesies that create a pretense between employers and their employees, create the fiction between employers and employees that the employees have any choice in the matter.

Can you imagine if your boss said “Would you mind getting me coffee?” The discourse of our work world has evolved in such a way that it’s impossible anymore to say, “I’d prefer not to.”

Well, Bartleby, the Scrivener presents the sort of nightmare scenario of your employee not getting it or deciding no longer to get it and no longer to say either, “Yes, of course, I’ll do your copying for you” or “Hell no, I won’t do your copying,” but instead appealing to you in a more human way.

The story of Bartleby is of course a terrible one. Our narrator not only offers Bartleby the option of coming home to his own home. Because he cannot get rid of Bartleby he moves out of his own office. But Bartleby won’t leave then either and the next people who rent the office have Bartleby hanging around on the stairs. Bartleby is eventually sent to the tombs in New York, where imprisoned, he dies.

Melville’s not kind to his readers. He doesn’t feel the obligation to pamper us, in fact, probably because by the time Melville wrote Bartleby, the Scrivener, he was almost as poor as Bartleby. And he wasn’t sure he had any readers anymore anyway, and so he just spoke the truth.

What Melville says to us, reminds us of, is that our systems produce persons so damaged that although we may put them out of our minds, evict them from our offices, they are still there. And in some way we are accountable to them. And the sign that Melville has no terrific solution is that he ends the story, “Ah, Bartleby; ah, humanity.” Right?

He directs our attention to a kind of cruelty that is the human condition. I’m looking for some cheer to offer in that story. I think what Melville does though, is he takes us further and further into the dark heart of modernity, where a growing complexity of the world produces more and more dysfunction and victimization.

Melville also admires the complexity. How amazing is it that we can light all of our lamps and we can all be reading all night because one thing you can’t do if you don’t have any light at night, is you can’t read. It was for readers that the oil industry was so important.

How amazing that we can – that we can illuminate whole cities out of out of these complex systems and at the same time – how amazing that we can create paper that gets shipped all over the world and at the same time what – what human cost this productivity leads to.

In Their Own Words is recorded in Big Think’s studio.

Image courtesy of Shutterstock