Wheels Down on Mars. Now It’s Time to Reinvent America, Says Neil deGrasse Tyson

It has been a milestone week for NASA, thanks to the successful landing of the Mars Curiosity Rover using a novel system. All the good publicity has helped feed the sentiment that NASA needs more money to do things like this more often. In fact, a campaign to fund NASA through Kickstarter has gone viral (#fundNASA).

That effort is commendable, but as Adam Lee and others have recently pointed out, a discussion still needs to happen about our public spending priorities, and that conversation needs to start with a hard look at ROI, or return on investment.

ROI is an area where NASA stands out from most federal agencies, as the money spent “up there” really does have a big payoff “down here” in the form of inventions that have become profitable products. There are, of course, entire fields that owe their existence to NASA (to paraphrase Barack Obama: you didn’t build that, NASA did).

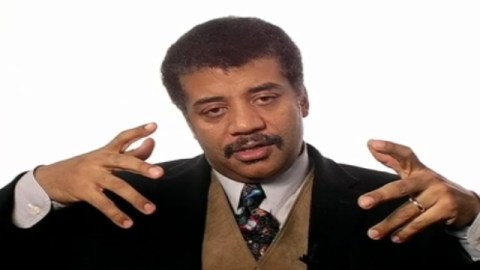

Then there are those intangible benefits of the space program that Neil deGrasse Tyson calls “the NASA Effect” (see him explain in the video below). According to Tyson, fully funding NASA “will stoke a pipeline of scientists and engineers as never before, and stimulate an entire nation to dream about tomorrow.”

So can the successful landing of Curiosity help galvanize support for a manned mission to Mars? If not, what motivation will the public need to support such a mission? We asked Tyson this in a recent interview, and here is his eloquent response, in full:

Neil deGrasse Tyson: So about a decade ago I realized that if we were going to go to Mars with people it would be really expensive and so I thought to myself what activities have human cultures engaged in in the past that were as expensive as what it might be to go to Mars and what motivated them to spend that money.

I was going to fill a whole book, “Motivations to do Great Things, Great Expensive Things,” and then I’d find the task. I’d find the activity that most closely resembled what it would be to go to Mars in the 21st century and I’d say “Oh, is that what that culture did with their population? Is that how they raised the money? Is that how they convinced the people?” I was going to fill a whole book of this. It would be a nice little reference catalog about how to get something done in modern times.

In conducting that exercise what I found is that there are only three drivers — not more, not less — three drivers that account for the most expensive, ambitious projects humans have ever undertaken. One of them is the praise of deity or royalty. That’s what got you the pyramids. They’re basically expensive tombstones. That’s what got the cathedral and church-building of Europe. That was a period where huge fractions of societal investment went into those activities. There is less of that today, so that’s not really a useful driver to think about how we might transform the 21st century.

Another driver is war. Nobody wants to die. That gets you the Great Wall of China. That gets you the Manhattan Project where we built the bomb. That gets you the Apollo Project.

Why did we land on the moon? We landed on the moon because we were at war with the Soviet Union and when we found out they were not going to the moon and they didn’t have the technology to go to the moon we stopped going to the moon. That should tell you that we did not go to the moon because we’re explorers and we’re discovers or we’re ambitious.

We went for military reasons and when the military reasons evaporate so too does your vision statement.

Another driver, the search for economic return, nobody wants to die—nobody wants to die poor–that’s what is responsible for the Columbus voyages, the Magellan voyages, Lewis and Clark. So if we’re going to go to Mars and if war is not the driver–because it could easily become the driver if you get another space race with someone we view as a military adversary. I wonder who that might be. But if peaceful heads prevail then war is not the driver available to you. Let’s check our list. Well kings and gods are not sufficient in modern times to undergo heavy projects such as that. What’s left? The promise of economic return.

You can go into space, transform society, change the zeitgeist of your culture, turn everyone into people who embrace and value science, technology, engineering and math, the stem field. Whether or not people go into space or serve the space industry they will have the sensitivity to those fields necessary to stimulate unending innovation in the technological fields and it’s that innovation in the 21st century that will drive tomorrow’s economies.

Any frontier in space now involves biologists. We’re looking for life. Chemists, geologists, physicists, mechanical engineering, electrical engineers, aerospace engineers, astrophysicists, all the traditional sciences and engineering frontiers are captured in any ambitious goal to explore space. We can recapture those times and reinvent America. We’ve already invented America once before. It’s ripe. It’s ready and it’s willing I think, to be invented again.

Neil deGrasse Tyson on “the NASA Effect”

Watch the video here:

Image courtesy of Shutterstock

Follow Daniel Honan on Twitter @Daniel Honan