Why Aren’t More Women Openly Skeptical of Faith?

In 2006 Wired contributing editor Gary Wolf wrote a story on emerging trends in atheism. In his skeptical piece Wolf coined “new atheism,” a term later applied to the “four horsemen”: Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, Daniel Dennett, and the late Christopher Hitchens.

These men had varying responses to the term. Harris, for one, pointed out that “atheist” never appears in the book that kicked off this movement, The End of Faith. Alas, the four horsemen are the usual go-to thinkers when considering atheism in the 21st century, which begs one important question: What about women?

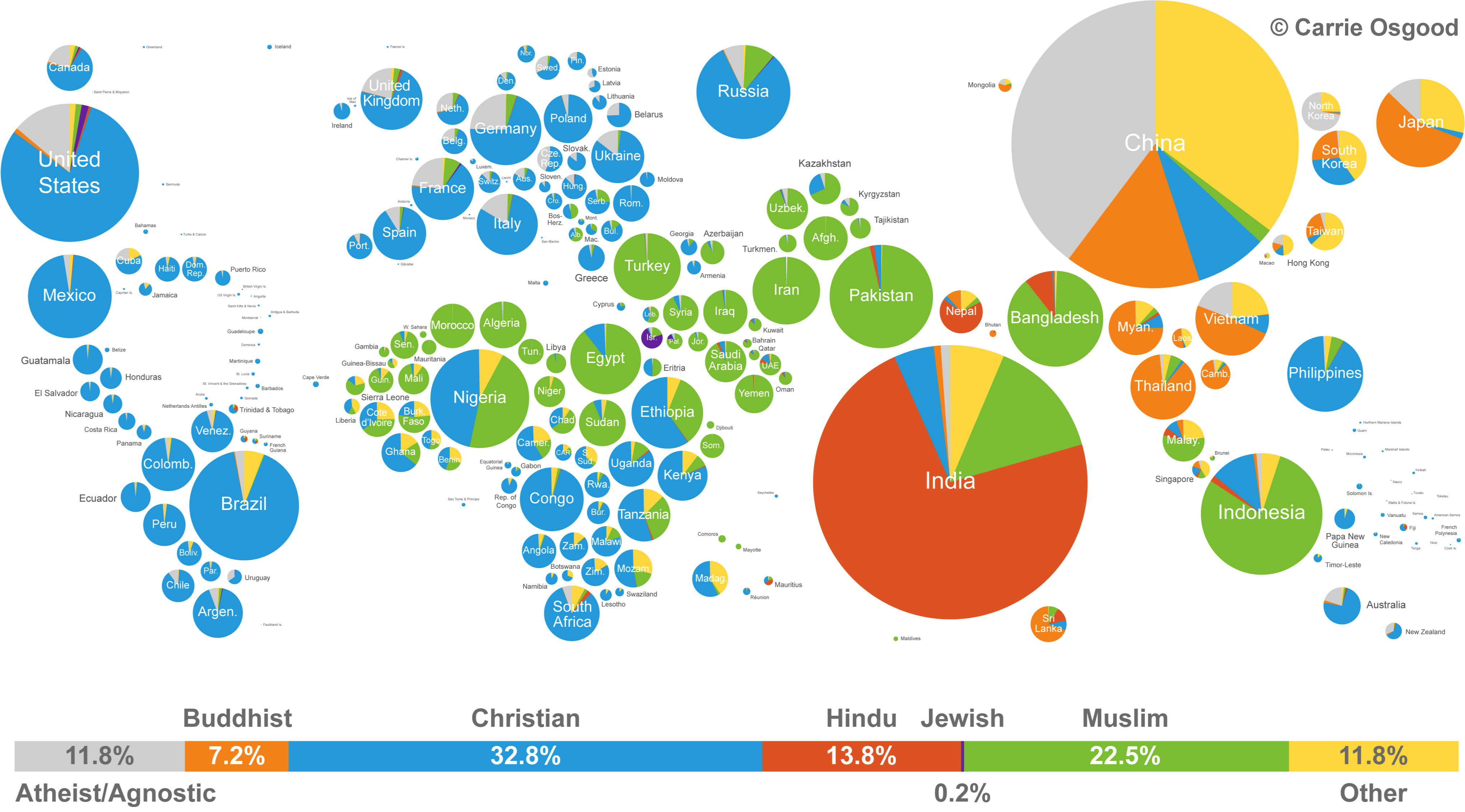

In general there are more male than female atheists. One 2010 survey found that males outnumber females in confessed atheism. In the United States that equates to 6 percent of men compared to 1.2 percent of women. (The “not religious” category is closer, as it is in most nations.) In Russia the number was 6.1 to 3 percent, whereas Switzerland it was 9 to 7 percent.

Numbers become confusing with examples like this 2012 poll, which reports that while women make up 52 percent of the US population they count for only 36 percent of “atheists and agnostics.” The problem with this differentiation is that everyone is agnostic, in that no one “knows” whether a god exists. You’re either theistically or atheistically agnostic. Many choose to not think much about it. That’s qualitatively different than pronouncing your atheism.

On top of that these are self-reported polls, and there might be reasons women do not claim their atheism. In a 2015 discussion, secular scholars Susan Jacoby and Rebecca Goldstein explore the question of why more women don’t profess critical skepticism of faith. They point first to social reasons: children of women who admit their atheism are more likely to be bullied at school, for example.

Personal beliefs are one thing, but social circles tend to be tight-knit. If your circle is comprised of devout followers, expressing atheism might ostracize you from this network, which could lead to larger problems for the entire household. Jacoby believes this is a driving factor of why some women stay “in the closet” regarding atheism.

Jacoby also points to an education gap. She says there is an “enormous deficit in math and science education between women and men.” The more educated one is in the sciences, she says, the more likely you are to be skeptical regarding divinity. While medical schools are seeing roughly equivalent numbers in terms of men and women, Jacoby reminds listeners there are very few female surgeons. Her preference appears to be for the more rigorous degrees.

There are other reasons. Humans are generally more reactive than proactive, and stringent religious dictates—President Trump announcing transgender people will not be allowed to serve in the military appeals to specific Christian sensibilities, for example—turn people off of religion and its questionable metaphysics. Sociology professor Phil Zuckerman believes this is turning many young people, specifically women, away from religion, as Kyle Fitzpatrick reports:

Zuckerman believes this has to do with traditional organized religions’ male-centrism: teaching women that they’re second class, must remain virginal, and must stay out of leadership positions. Pair this with the amount of women in the workplace rivaling men, and the group doesn’t need to turn to a church for social or financial support that churches typically offer.

This is an important about-face for women willing to declare their unbelief. In the Los Angeles Review of Books Zuckerman writes about Elmina Drake Slenker, the mid-19th century ex-Quaker atheist who scandalized the nation when she publicly declared her atheism in 1856. She was prosecuted shortly thereafter. Zuckerman points out her actual “crime,” which led to months in prison because she refused to swear heavenly allegiance on a bible:

Writing leaflets and personal letters to various people about human sexuality, marital relations, birth control, and bestiality. She was put on trial, and it only took the jury 10 minutes to find her guilty.

How things have changed. Instead of submitting to public pressure and governmental interference women have, thankfully, fought back, especially when they’ve been personally affected by religious mandates. Ayaan Hirsi Ali still remains a contentious figure in Islam, where she’s constantly harassed by dogmatic followers, but her secular foundation, dedicated to combating the ravages of archaic religious displays of power, such as female genital mutilation and honor violence, is flourishing.

Technology has helped aid such movements. Jacoby believes many female freethinkers existed in the past, but their voices were never heard since publishing was a male game. Women who broke through often had to assume male monikers just to do so. With easy access to social media this has changed dramatically.

Jacoby believes the next step in inviting more women into the fold requires educating people that morals are not dependent on religion. She expresses disdain for those who feel that moral decisions depend on religion or what she finds to be an innocuous term, spirituality.

The statement “I’m spiritual but not religious” makes me want to throw up. What this sentence means is I’m not religious, I don’t go to church, but I am a good person. And this word spiritual comes to stand for being a good person, just as people were talking about religion as a transcendent experience, as if it’s different from what people experience when they listen to great music.

She admits women appear to be more religious than men thanks to biology and a penchant for spirituality. During their talk Goldstein points to social psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s work on purity as one possible motivation for religion: women tend to associate more with the concept of being “pure” in part due to its long history of patriarchic power structures. Both women agree that a link between spirituality and sexuality also align more women than men with religion.

And both women agree that intellectual equality and freedom will even the gender playing field regarding atheism. Jacoby states that comforting people in the face of tragedy—she cites Newtown as an example—is possible without an allegiance to a metaphysical figure or a prophet. Reason, she says, is more likely to foster relationships based on equality and sharing, as the pretensions of right and wrong promoted by religious ideology dissolve. What you are left with is our human nature, fallible and beautiful, imperfect though empathetic, no deity required.

—

Derek’s is the author of Whole Motion: Training Your Brain and Body For Optimal Health. Based in Los Angeles he is working on a new book about spiritual consumerism. Stay in touch on Facebook and Twitter.