Better leadership in 3 “Sketchplanations”

- Sketchplanations creator Jono Hey offers three perspectives on the age-old question: What makes a great leader?

- In practical terms, what can we learn from others to improve our leadership skills and those of our teams and colleagues?

- Hey puts his unique spin on the ideas of David Marquet, Dan Pink, and Benjamin Zander.

What makes a great leader? And what can we learn from others to improve our leadership skills and those of our teams and colleagues?

Over the past two decades, I’ve explored these questions from two distinct perspectives.

The first is practical: At 22, I found myself leading a Bangalore-based team of 40 software developers from an office in Belgium. Later, at the University of California at Berkeley and Stanford, I studied what made product design teams tick, which teams gelled and thrived, and which slumped. And I saw what kept students awake and focused rather than sleepy and checking their devices.

I also worked with high-performing teams at Jump Associates, a growth strategy firm, and held leadership roles at Nutmeg and Zen Educate, two successful UK tech startups. These experiences shaped my understanding of effective leadership by learning directly from leaders — what worked and what didn’t.

These experiences allowed me to learn from the leaders around me and see what works and, especially, what doesn’t.

The second perspective is through Sketchplanations, where I’ve spent years explaining complex ideas through simple sketches. What began as a personal challenge to develop clear explanations has become a widely shared project.

Leadership is a topic I’ve returned to again and again with the frameworks that work for me and that others can benefit from. Sketches help distill these ideas into memorable and actionable insights, reaching a wider audience than if they were confined to books and articles.

Here, I share three leadership lessons that have profoundly shaped my approach and provide both principles to reflect on and practical tools.

Let’s dive in.

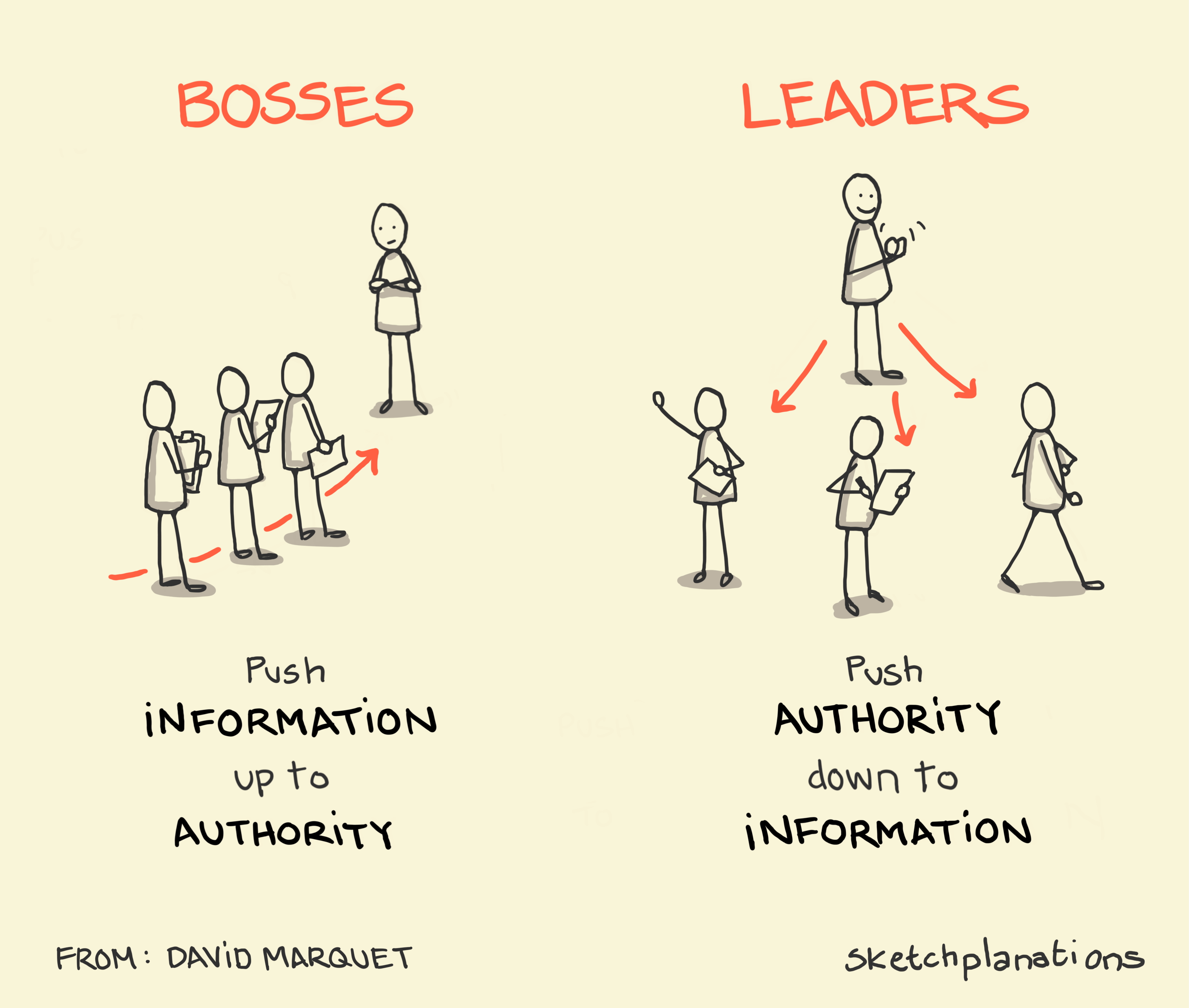

The difference between a manager and a leader

A leader’s time is limited. With such a high-leverage role, it’s key that leaders spend time on the organization’s most important decisions. But with so many things going on, it’s easy for a leader to get sucked into less significant activities, be that whether someone can take a vacation in three weeks or far-removed incidents.

A leader’s decision-making speed determines how fast the organization moves. If the leader can’t make decisions in time, progress bottlenecks — everyone waiting for critical time with the boss before moving forward.

Many decisions require detailed information that a leader first has to understand before they can make a decision. And who usually has that information? The employees bringing the situation to the leader.

Experiencing this first-hand, ex-nuclear submarine captain David Marquet — who knows a thing or two about leadership — adopted a different approach. Rather than pushing information to authority to assess and decide on, he pushed authority to those with the information.

When I adopted this approach, I immediately freed my time for the more strategic and high-value work my organization needed from me. My team no longer waited for my input on routine matters, and I could focus on where I added the most value.

Delegating decisions also boosted my team’s autonomy and motivation. While freeing my time for maximum value, my team also developed leadership skills by making decisions and owning outcomes. Some steering is necessary as leaders discover where they are most needed and as the team practices their authority. But every time something is complete by the time I hear of it, it feels like a blessing.

Leaders thrive when they focus on high-impact work. Delegating authority where the information already resides ensures this and develops new leaders across the organization.

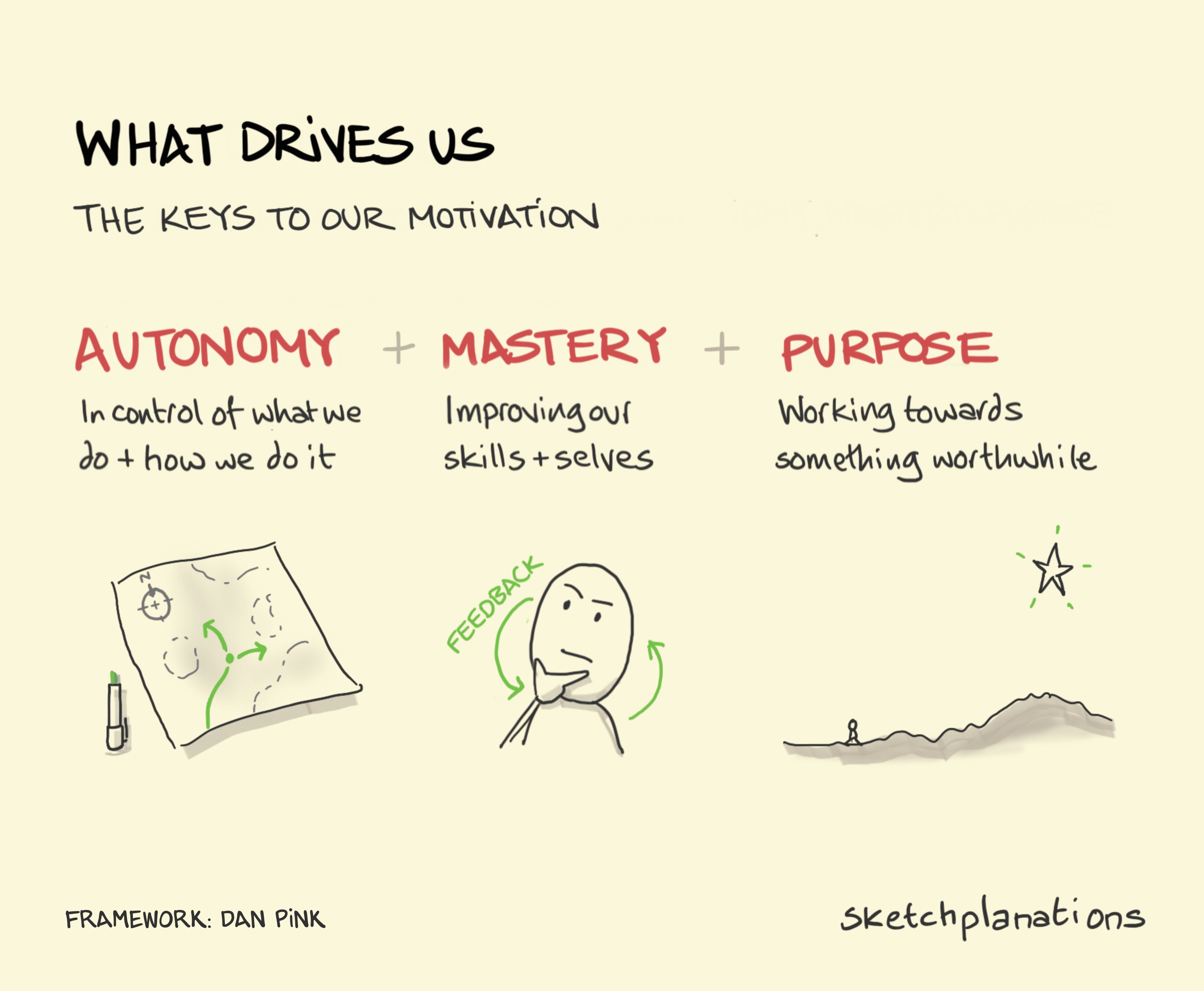

Tap into “autonomy, mastery, and purpose”

Leading requires that we get the best out of those following us. A powerful way to achieve this is through “autonomy, mastery, and purpose” — a framework from Dan Pink’s book Drive.

He describes an evolution of motivation. At first, survival was our motivation — we looked to meet our basic needs. Later, leaders considered extrinsic motivations: rewards for good behavior and punishments for bad. But the most compelling is tapping into intrinsic motivation — motivation from within ourselves — driven by desires for autonomy, mastery, and purpose.

Autonomy is the antithesis of micro-management. A boss hovering over your shoulder, directing your every action, robs you of agency and satisfaction in your work. Dan Pink suggests conducting an autonomy audit for your team. It’s easy for a leader to think they are providing more autonomy than they are.

Mastery is intrinsically satisfying. Whether whittling a stick while camping or folding the perfect paper airplane, we’ve all felt joy in improving our skills, no matter how significant the outcome. When I stop learning in a role, it signals to me that it’s time to change. I try to ensure that my team always develop skills they value and have the opportunity to become masters in their craft.

Purpose and vision-setting are requirements for inspiring leaders. Everyone needs to understand the why behind their actions. If you believe your work is for nothing, or worse, may harm, how much effort will you put in? The purpose is likely clear to you if you’re in a leadership position. You must make it clear to everyone in your teams, too.

If you have a demotivated team or a 1:1, run through a mental checklist asking:

- Do they have sufficient autonomy in their work?

- Are they developing skills toward mastery in their field?

- And do they have a clear purpose to work towards?

One or more of these are lacking in almost every case of a demotivated individual I have encountered.

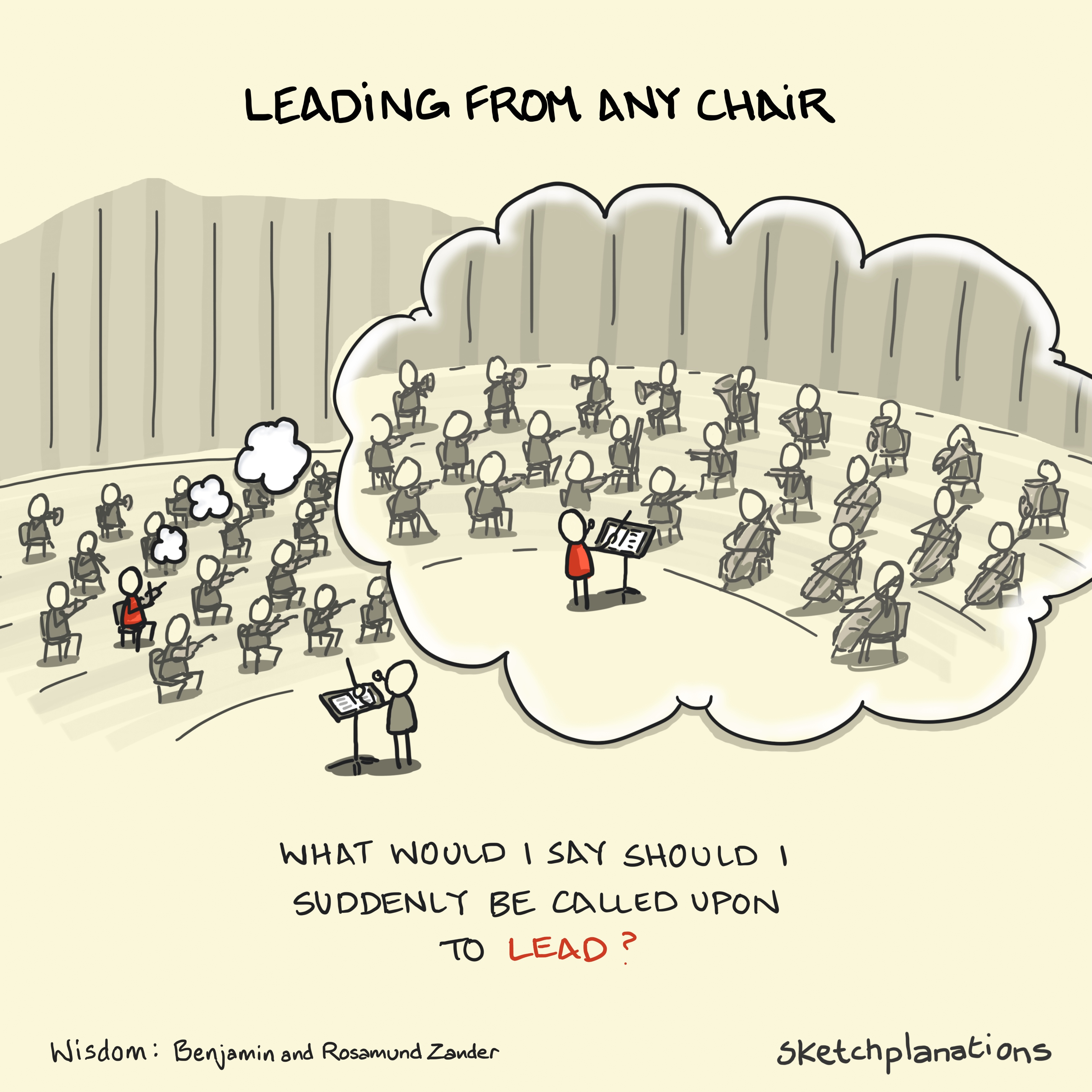

Leading from any chair

A symptom of our time, or our nature as human beings perhaps, is that we adopt the roles given to us. But leadership isn’t tied to a title. It can come from anyone, anywhere.

In The Art of Possibility, co-author Benjamin Zander shares a story from the celebrated violist Eugene Lehner. Zander posed a probing question to Lehner: “How can you bear to play day after day in an orchestra led by conductors, many of whom must know so much less than you?”

Lehner reflected on an experience from his first year with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. In a rehearsal led by conductor Serge Koussevitsky, the orchestra struggled through a challenging Bach passage. Nadia Boulanger, a conductor and friend of Koussevitsky, was observing the session. Koussevitsky paused and asked Boulanger to conduct so he could hear the music from the back of the hall. She stepped in seamlessly, guiding the orchestra through the passage before returning the baton to Koussevitsky.

The incident left a lasting impression on Lehner, planting a question in his mind: “What would I say to the orchestra, should I suddenly be called upon to lead?” Reflecting on this, Lehner explained, “It’s now 43 years since that happened, and it is less and less likely that I will be asked. However, in the meantime, I haven’t had a single dull moment in a rehearsal as I sit wondering, ‘What would I say to the orchestra, should I suddenly be called upon to lead?'”

As Lehner suggests, learning the skills and thinking of a leader is available to all of us, even if we’re not nominally in that position. There may come a time when we’re called upon to lead, or there may be a void that a grateful leader needs us to fill, or we may simply need to direct our actions and those of the people around us.

Considering what we would do if we were in a leadership position hones our instincts. Just as Lehner did in every rehearsal, it allows us to practice what Peter Drucker called “feedback analysis”: making our best prediction of what will happen and comparing it to what does happen. Comparing our choices with results is how we learn.

So, I encourage everyone to ask, “What would I say should I suddenly be called upon to lead?” It’s a question worth asking every day, in every role.

Practical tools and deep principles for leadership

These three ideas — pushing authority to information, tapping into our intrinsic motivation, and leading from any chair — have served me time and again as I navigated difficult situations at work. And I’ve seen them exemplified by exceptional leaders over and over.

The best ideas work as daily tools and principles for long-term reflection. I hope you can apply elements from each immediately and also reflect on them years later, as I do. And if you skipped straight to the end, perhaps the sketches themselves will do much of the work of reading this article exactly as they should.