Why “action bias” proves the smart move can be no move at all

- “Action bias” is the mistaken impulse to value effort and movement over the best odds of success.

- In many instances, we often assume that taking action and being busy is effective. However, action bias can lead to more harm than good.

- There are practical ways to avoid action bias and make better decisions in business.

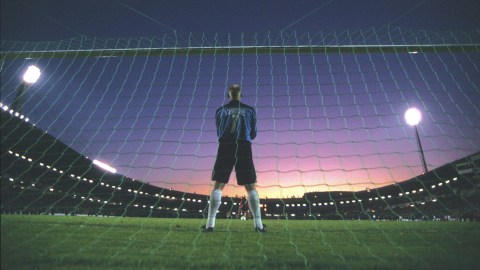

Three people sit in a room and watch hours and hours of old soccer footage. They’re looking at penalty kicks. These three judges have been asked to look at 311 penalty kicks and to note down where the kicked ball goes, where the goalkeeper jumps, and whether it was successful or not. And they found out something bizarre. The optimum strategy if you are a goalkeeper is not to dive to one side or another but to stay put in the middle. On average, 20% of goals will be saved. If you stay in the middle and don’t move at all, you have a 33% chance of saving the goal. That’s a huge increase in likelihood in a hugely important area of the game.

There is a lot of money in soccer, and there are a great many statisticians researching these kinds of things. It wouldn’t be hard for coaches, players, and goalkeepers to find this out. So, you’d expect goalkeepers to employ an optimum strategy and stay put. In fact, only 6% of goalies will do so. In the overwhelming majority of cases, they will dive to either the left or the right. But why?

It is due to something called “action bias,” where we will value something more — or excuse a failure more readily — if it comes after some active effort. In other words, we tend to think that doing something is better than doing nothing, even if the action is not the most effective or logical choice. If your team lost the FIFA World Cup final to a penalty and the goalkeeper didn’t move, they would be lampooned as a feckless potato. If, though, they had dived, stretched, and landed in a painful ball, supporters would say, “Ah, well, he tried his best.” The fact is, he may have demonstrated great acrobatic effort, but he didn’t play the best game. He didn’t play the odds.

The broad reach of action bias

Action bias extends far beyond the soccer field. It is in almost every walk of life. We often assume that movement means progress and that if we do something, we can control things. If you pay someone a lot of money, you might think that person needs to get busy. They need to do a frantic myriad of things to justify the price tag. Likewise, if you have been paid a lot of money, you want to prove to your clients that you are a go-getting, proactive sort. You fiddle, poke, twist, and pointlessly reposition things. Last week, I had a healthy laugh at a BBC presenter’s fake typing at the end of a news segment. We are primed to think that being busy is good and action is effective.

Often, though, this can lead to more harm than good. The ancient Greeks had a word for this when applied to medicine: iatrogenesis. Before the invention of antiseptics and modern germ theory, the vast majority of medical interventions likely would have worsened the condition. For invasive treatments like surgery or amputation, this was almost always the case. The best physicians in the ancient world were those who were hands-off and minimally invasive. Before modern times, as Voltaire put it, “The art of medicine consist[ed] in amusing the patient, while nature cure[d] the disease.”

Take action bias out of business

Knowing about action bias allows us to avoid it. A goalkeeper who disregards the booing and heckling of the statistically ignorant crowd will increase his save rate by 13 game-changing percentage points. So, here are three takeaways.

Hold your nerve when investing. If you have invested in something and your investment takes a downturn, the instinct is to step in. Action bias is whispering in your ear, and it’s saying, “If you don’t meddle now, things will get worse.” But a lot of times, this isn’t the case. Investments go up and down. There are good months and bad months. The important point is to see growth over time. As the economist Paul Samuelson put it, “Investing should be more like watching paint dry or watching grass grow. If you want excitement, take $800 and go to Las Vegas.”

Just observe. When Big Think+ sat down with the author and strategist, Ryan Holiday, he offered some great advice: “To be successful… talk to everyone involved first. Take some time just to simply observe and understand the terrain of the position [you’re] going to be in.” When you arrive at a new job or in a new role, don’t assume you need to change everything and leave a mark. Jumping from one thing to another is not an efficient or successful strategy. Holiday gives the example of John DeLorean, an executive at General Motors, who “was chasing colored balloons. He was just sort of running from project to project.” The problem, Holiday concludes, is that “[when] we just wing it, it doesn’t work.”

Sleep on it. We all make impulse decisions from time to time. Sometimes, as in avoiding a car collision, for instance, they can be life-saving and essential. At other times, though, they can be damaging. Impulse decisions are those that seek quick, short-term benefits while ignoring or being ignorant of the potential long-term negative consequences. Sound advice for any major decision — in business or real life — is to sleep on it. If we receive an angry email from a grumpy client, it can be tempting to reply instantly. But this often risks overpromising, overcompensating, or misjudging the response. Action bias inclines us to reply straight away, but wisdom lies in taking your time.