How Botticelli shaped the modern notion of beauty

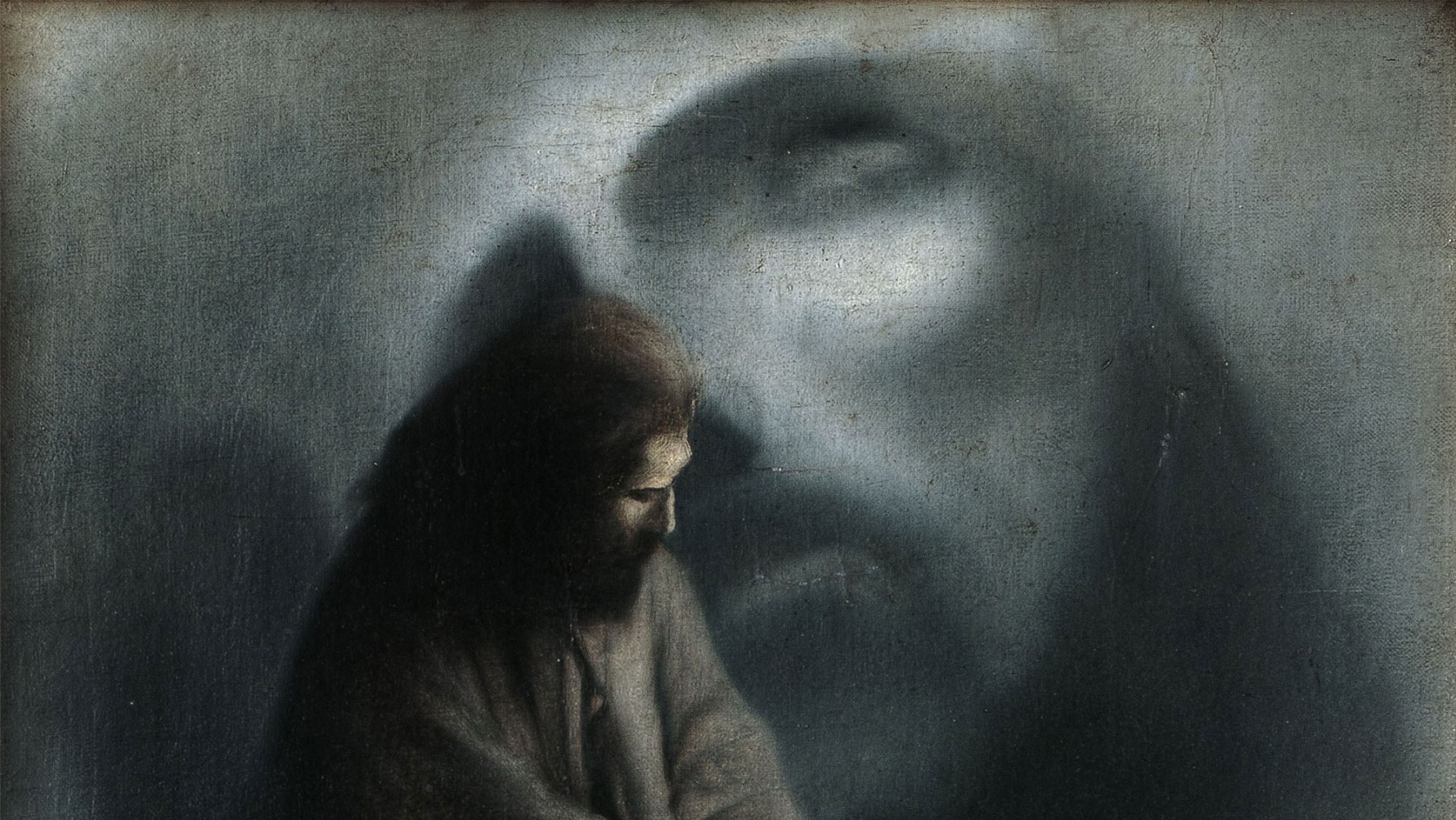

Image source: Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987): Details of Renaissance Paintings (Sandro Botticelli, Birth of Venus, 1482), 1984

“Has anyone ever told you that you have the face of a Botticelli and the body of a Degas?” Robert Downey, Jr.’s Jack Jericho character says to countless women in the 1987 film The Pick-Up Artist. This borrowing art history for the art of seduction picks up on an essential truth: Renaissance painter Sandro Botticelli set the modern idea of a pretty face over 500 years ago.

But it wasn’t always so, with Botticelli’s beauties falling into obscurity until his personal renaissance in the 19th century, when a new generation of artists and tastemakers took a fresh look at his art. From modern fashion to modern art (such as Andy Warhol‘s take on Botticelli’s Birth of Venus shown above), we’ve all been “feeling” Botticelli’s faces without realizing it.

Yet, if Botticelli knew his artistic afterlife, he would despair over how the public “Can’t feel my face.” While fellow Renaissance artists Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo reached mythic status, Botticelli failed to reach any audience at all, popular or critical, until the late 19thcentury. It’s amazing that the first critical monograph of Botticelli didn’t appear until 1893, especially considering his popularity during the Renaissance. Botticelli’s 1486 Birth of Venus brought the classical concept of sexy back to the Renaissance generation that not only found a peaceful coexistence with the heavily religious art of the time, but also achieved cult status with rich patrons.

The Gemäldegalerie–Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany, hosts The Botticelli Renaissance, the new exhibition focused on Botticelli’s modern connections, in no small part because of their collection of Botticellis, the largest outside of Botticelli’s native Florence, including Venus (shown above), a 1490 outtake of his leading lady from his signature work. Ripped from her mythological context, Venus shows off all her curves and openly simple, yet unforgettable face. But why did the cult of Botticelli’s Venus disappear?

Image:Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The Daydream, 1880. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Quite simply, times and tastes changed. The classical ideal reborn in Botticelli’s paintings fell victim to new ideals of beauty that matched the changing social mores. Other depictions of female beauty, such as the fleshier, heftier Rubenesque, crushed Botticelli’s willowy Venus in the popular imagination. Not until the mid-1800s, when the British Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), founded by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, and John Everett Millais, did Botticelli’s Venus rise again.

The PRB believed that Botticelli’s fellow Renaissance painter Raphael had corrupted painting and led to the Mannerism of succeeding generations that turned art into a mechanical process ever since.

Reaching back into art history before Raphael, the PRB plucked out Botticelli, whose Venus was reincarnated as a succession of femme fatales such as the subject of Rossetti’s The Daydream (shown above, from 1880). Rossetti even owned a portrait by Botticelli to better study the master firsthand. Similarly, although Walter Pater‘s remembered most today for his prose poems dedicated to Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa as the “Lady of the Rocks,” he also sang the praises of Botticelli’s ideal beauties. By the end of the 19th century, right at the dawn of modern art in the 20th century, Botticelli and his Venus were hot again.

Image:Edgar Degas. Venus (after Botticelli), 1859. Peter Schälchli, Zürich.

Even artists who took paths to beauty felt they had to go through Botticelli first. Shades of Jack Jericho, even Edgar Degas sketched Venus (after Botticelli) (shown above) during visits to the Uffizi Gallery in 1858 and 1859. The body Degas eventually became famous for took a different shape, but here we can see how he was fascinated by Botticelli before moving on to more Impressionist depictions, which, in turn, set the stage for every modern art movement that followed — either in following or turning away from that ideal.

The 20th century ideal of female beauty — face and body — thus had 16th century origins. But how to clothe that body? French designer Elsa Schiaparelli tapped into her inner Botticelli in designing a woman’s evening dress (shown above) for the fall 1938 season. As all of Europe descended into the Second World War, Schiaparelli matched that dark mood with a black crêpe silhouette no Rubensque beauty could squeeze into. Couture embroiderer François Lesage made the Botticelli connection clearer by adding semi-detached leaves and pink flowers — the motif of Botticelli’s famous Primavera and other springtime portraits — to suggest the gowns worn by his Earth-bound goddesses.

From Schiaparelli’s throwback fashion sense it’s a small step to the present-day commodification of Botticelli’s idea of beauty. Warhol‘s Details of Renaissance Paintings (Sandro Botticelli, Birth of Venus, 1482) (top of post, from 1984) illustrates how the classically timeless ideal of beauty Botticelli revived now finds itself cropped and digested for mass marketing, an eternal grace edited down to 15 minutes of fleeting, disposable fame.

Following in Warhol’s wake, Japanese artist Tomoko Nagao‘s digital print Botticelli — The Birth of Venus with Baci, Esselunga, Barilla, PSP and EasyJet (shown above, from 2012) makes the commodification comically explicit while simultaneously displaying the distance between Botticelli’s painterly craft and the pernicious digital ease of modern advertising. Nagao juxtaposes her digital Venus — female beauty chopped down to the simplest of lines — with a sky full of EasyJet advertisements above, a sea full of Barilla pasta ads below, and a video game controller replacing the classic seashell.

The Botticelli Renaissance almost effortlessly spans a half millennium like Venus herself riding the surf to show how our concept of beauty owes much to Botticelli, but loses much in time’s translation. If we can’t “feel” Botticelli’s ideal face (and body) anymore, we only have ourselves to blame.

—

[Many thanks to the Gemäldegalerie–Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany, for providing me with the images above and other press materials related to the exhibition The Botticelli Renaissance, which runs through January 24, 2016.]

[Please follow me on Twitter (@BobDPictureThis) and Facebook (Art Blog By Bob) for more art news and views.]