Unregulated Use of Facial Recognition Software Could Curb 1st Amendment Rights

117 million Americans have had their faces scanned by facial recognition software, and put into databases searchable by local, state, and federal authorities, a Georgetown University report finds. This accounts for about half of all US adults. Researchers at the Center on Privacy and Technology penned this worrisome report entitled, “The Perpetual Lineup.” Any person it seems can be accessed or followed at any time and for any reason, calling into question just how important citizen’s privacy actually is. If you have a driver’s license photo, chances are you are in this everlasting lineup.

Another revelation, such software carries a racial bias. African Americans and other minorities were far more likely to have been entered into a database. 50 civil liberties groups, including the ACLU, petitioned the Justice Department to investigate this software’s use, as regulation of any kind was absent in almost all cases.

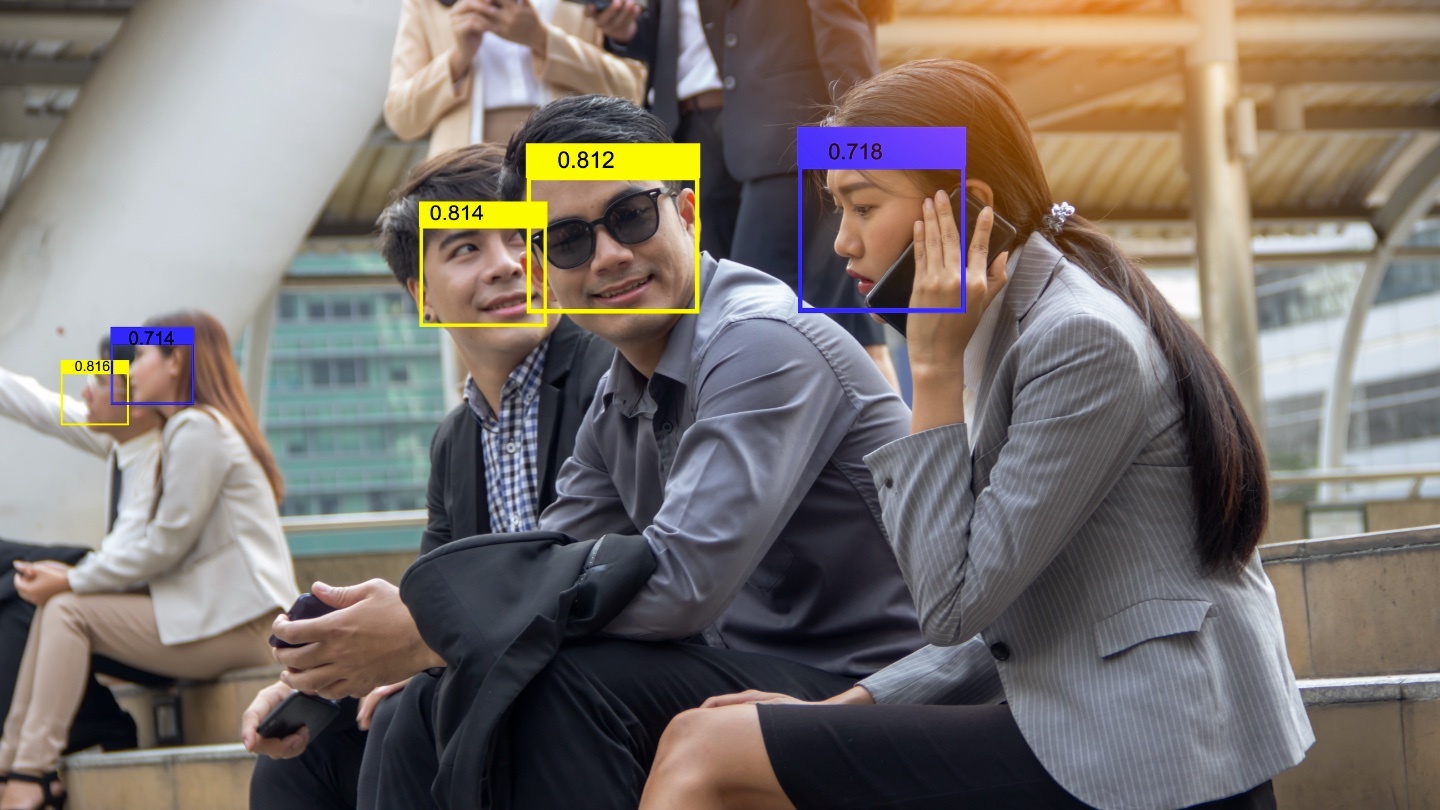

106 police departments were included in this report. Today, local police rely on real-time facial recognition programs more and more. Go for a stroll in one of several major American cities, and the police could be monitoring you without your knowledge. Some department’s even used driver’s license databases to catalog citizens.

New report shows that local police and the FBI use facial recognition software with little oversight.

The ACLU cited the software’s use in Baltimore as an example, a predominantly black city. Tens of thousands of arrests took place for minor offenses there over the last few years. Often, prosecutors drop the charges in such cases. Yet, those same people, innocent in the eyes of the law, had their faces logged into a database, and could easily be monitored by law enforcement on any level.

Stephen Moyer is the secretary of the Maryland department of public safety and correctional services. This is the agency responsible for the employment of facial recognition software in Baltimore and elsewhere in the state. Moyer defended the program in a statement, saying, “Maryland law enforcement agencies make use of all legally available technology to aggressively pursue all criminals.” Georgetown’s report does not blame any particular police agency, but the lack of oversight and regulation itself. Yet, out of 52 local police departments evaluated, only one had provisions to protect citizen’s first amendment rights.

In Baltimore, the ACLU uncovered that police used facial recognition software to target demonstrators at the Freddie Gray protest last year. The software scanned social media activity, so police could identify and arrest those protesters with outstanding warrants. A company called Geofeedia monitors social media on behalf of law enforcement. It was revealed that Twitter and Facebook provided Geofeedia with users’ data, helping police recognize those with outstanding warrants. Geofeedia is no longer receiving such data, we are told.

The ACLU found that facial recognition software helped Baltimore police target Freddy Gray protesters last year.

If you find these actions surprising, consider that Facebook and Google are currently embroiled in a class action lawsuit in Illinois, where each company allegedly added users’ facial images to a database without their permission. Legislators have also been approached by representatives of both companies about removing laws pertaining to user consent.

The unearthing of the FBI’s “face recognition unit” was particularly chilling, as it was made up mostly of “non-criminal entries,” or normal, everyday citizens. Here, facial images were obtained via passport photos, visa applications, and driver’s license photos. 16 states have reported allowed the FBI access to their driver’s license database.

Georgetown researchers spent a year and issued 100 police document requests, in order to complete this study. It is the most comprehensive report on facial recognition software use by law enforcement to date. Investigators suggest a legislative approach to prevent police departments from using driver’s license photos and relying on mugshots, instead. Another thorny issue is inaccuracy. Only one out of every seven matches is correct, according to the FBI’s own figures. That means a lot of erroneous matches, and the possibility of innocent people being monitored, or worse.

According to a 2012 study, which this report corroborates, the algorithms used in such software is 10% less accurate when it comes to people of color, young people, and women. It has a particularly hard time identifying those with dark skin. Since a lot security cameras are perched up high, many of the shots are of the top of someone’s head, which makes positive identification even harder.

Facial recognition software is often wrong, especially when it comes to people of color, which may mean a lot of false arrests and more tensions between minority communities and police.

The Georgetown report calls for more accurate technology be used. Meanwhile, the coalition of civil rights organizations asked the DOJ to focus its investigation on those departments using such software who are already under investigation for racial bias in policing. They also asked for assurances that these systems won’t purposely target minorities.

The ACLU’s legislative counselor Neema Singh Guliani said the results could stifle free speech, if no oversight is employed. This technology became pervasive before restrictions could be applied, she said. Now hopefully the problem will be rectified. “That’s really a backwards way to approach it,“ she said. “This is already being used against communities it’s designed to protect.”

To learn about the technology itself, click here: