Study compares school shootings in the 21st century to the last: What’s changed?

As the reverberations of the Parkland school shooting continue, many are wondering if any advances in gun legislation will be made. As debates are waged over the significance of gun sales and mental illness, a new study, published in Journal of Child and Family Studies, examines the differences between school shootings in the previous century and the current one.

Lead author Antonis Katsiyannis, a distinguished professor at Clemson University, believes that school violence is an epidemic that must be addressed. While some believe the Parkland incident, the deadliest school shooting in American history, is an isolated occurrence, Katsiyannis and team show otherwise.

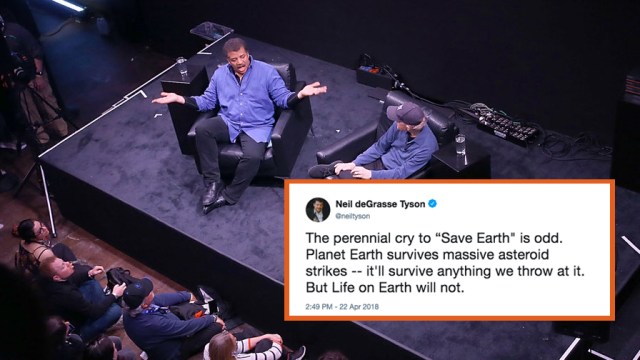

On the anniversary of the Columbine shooting, thousands of New York teenagers walk out of school to attend a gun control rally and call for sweeping reforms in national gun laws, on April 20, 2018 in Washington Square Park in New York City. (Photo by Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis via Getty Images)

Beyond the emotional headlines, gun-related violence in the United States has become a serious financial burden, with a $174 billion price tag. Although only deadly incidents like Parkland generally make national headlines, in 2014, students age 12-18 experienced over 841,000 nonfatal school victimizations, with another 545,000 incidents occurring outside of school. During 2013-14, 65 percent of public schools documented at least one victimization incident, totaling 757,000 crimes. The following year, six percent of students reported being threatened with a weapon. The study reports:

In addition, 5.6% of students reported missing school one or more days because they felt unsafe and 4.1% reported carrying a weapon during the previous 30 days. Though violent deaths at school are rare, 53 school-associated violent deaths occurred from July 1, 2012 to June 30, 2013.

Though the dominant number of incidences of bullying, violence, and threats occurred without a weapon, the paper notes that gun access is the “best predictor of gun deaths.” And despite recent calls to arm teachers following the Parkland shooting, the paper makes it clear there is no indication that armed guards or citizens reduce the number of deaths or injuries.

Not that all is lost. As the team writes, the federal ban on assault weapons and large capacity ammunition magazines, which expired in 2004, resulted in a decline in gun violence. After the ban expired, sales of arms with large capacity magazines surged from 10 percent to 34 percent of total weapons. Likewise, the Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1990, which imposed criminal penalties for possession or discharge of firearms, curbed gun violence in schools.

Given the high number of school shootings, a post-Columbine study by the U.S. Department of Education identified key factors in school gun violence, concluding that such incidents are not “sudden or impulsive”; others knew an attack was imminent; most attackers do not threaten ahead of the incident, though they do exhibit troubling patterns of behavior; most attackers felt bullied and were coping with personal losses or failures; and the attackers have access to guns. Despite a hope on the reliance of profiling, the study found that there is “no accurate or useful profile of the attackers.”

For purposes of this paper, the authors set their own standards for mass school shootings, as the FBI currently has no definition. (A mass murder means four or more people were killed during one incident.) Focusing on grades K-12, and excluding gang violence and university incidents, they write:

We define mass school shooting as a situation in which one or more people intentionally plan and execute the killing or injury of four or more people, not including themselves, using one or more guns, with the killings or injuries taking place on school grounds during the school day or during a school-sponsored event on school grounds.

The first documented shooting fitting these criteria occurred in 1940; the data run until Parkland in 2018. There were no such shootings throughout the fifties and sixties, until the second shooting in 1979. The nineties represented the peak, though our current era, the 2010s, represents the highest number of deaths due to such shootings.

This led the authors to conclude that “mass school shootings present an epidemic that must be addressed.” In 2016, the CDC declared firearm violence a public health crisis. The data confirm this on school grounds: in the 18 years of this century, we’ve already experienced more gun deaths from mass school shootings than during the entirety of the last century (going by the criteria set above).

Katsiyannis calls for a change in public policy and the law. This includes a removal of the current restrictions on firearms violence research, more funding to better understand the impact of school shootings, supporting organizations that conduct such research, and strengthening President Obama’s executive orders addressing school safety after Newtown. The authors conclude by writing:

Deliberate and sensible policy and legislative actions, such as expanded background checks and a ban on assault weapons, along with expanded support to address mental health issues among adolescent students and adults and other related preventative measures will likely reduce the occurrence of such events in the future.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Facebook and Twitter.