The fifth leading cause of death in the U.S.? Your job.

We hear about killers all the time: cancer; opioids; heart attack; stroke; traffic accidents. Yet there’s another murderer that one Stanford professor claims to be the fifth-leading cause of death in America, claiming over 120,000 lives and between 5 and 8 percent of annual health care costs: your job.

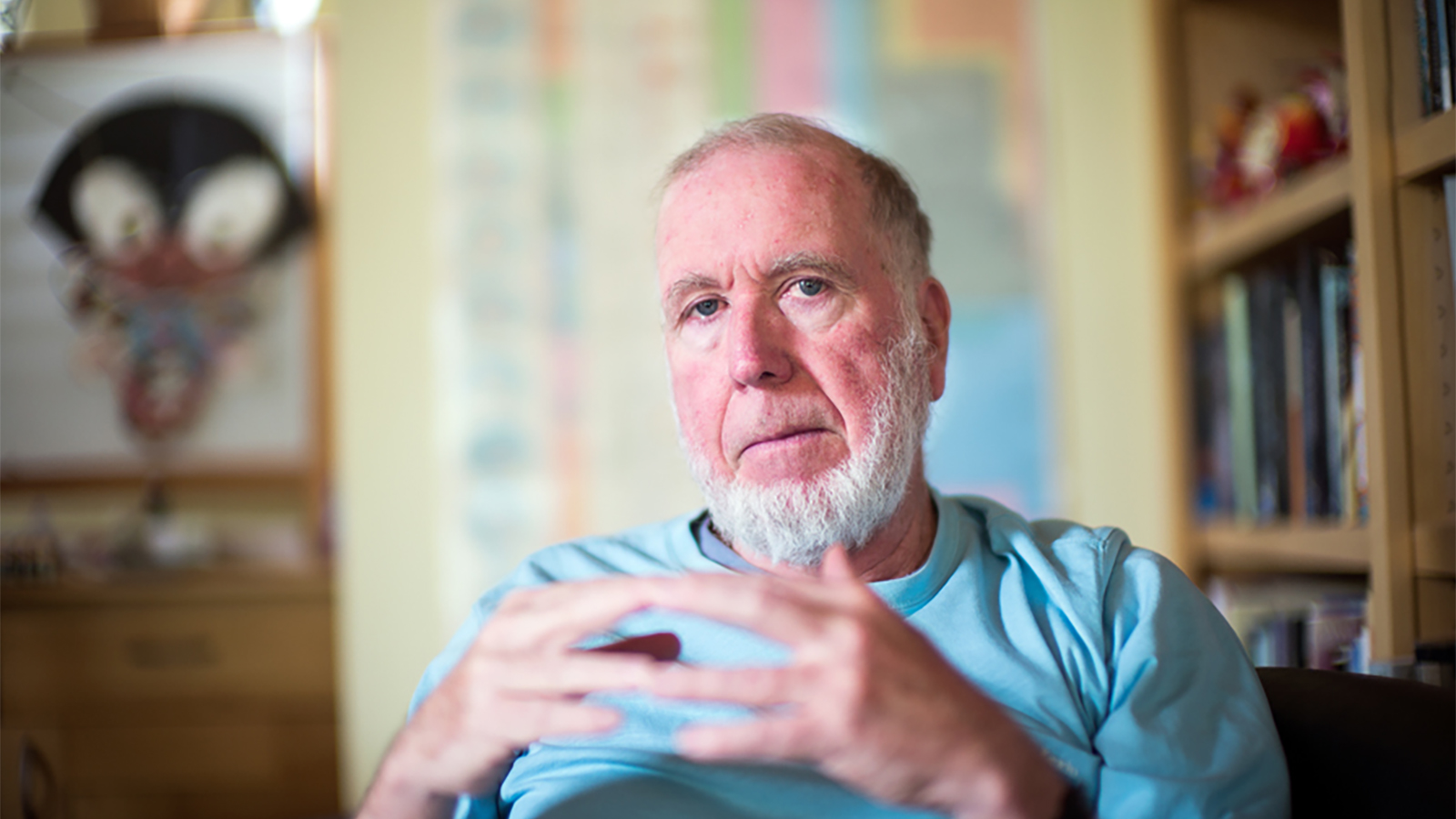

Jeffrey Pfeffer, a professor of organizational behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business, compares his new book, Dying For a Paycheck, to Rachel Carson’s 1962 classic, Silent Spring. Pfeffer aims to influence our understanding of the modern workplace in the same manner that Carson’s book rang the alarm on the imminent danger of chemical consequences.

Pfeffer estimates two million instances of workplace violence occur every year, with many cases going unreported. While the number of workplace murders is dropping slightly, he argues that a different type of violence is being conducted. A lot of emphases is placed on physical health and injury avoidance, yet little regard is paid to our mental and emotional health.

For the most part, the emphasis remains on preventing occupational injuries and exposure to hazardous physical conditions coupled with encouraging health promotion programs, with comparatively limited attention focused on changing the psychosocial dimensions of work that have profound effects on health.

Chronic diseases account for 75 percent of US health care costs. As stress is a driver, especially in regards to cardiovascular and metabolic disorders, we have to investigate what is driving its preponderance. Factor in drug and alcohol abuse, which is often associated with dealing with stressful environments, and the toxic relationship between livelihood and mental and physical health becomes clear.

In his book, Pfeffer cites a number of studies linking happiness and health. Happiness is challenging while in ill health. Unfortunately, chronic diseases, as their very name implies, take years and even decades to manifest into full-blown disorders. They come on like tinnitus: an occasional, then constant, ringing in the background of every waking moment. You soon adjust to its annoyance until, one day, hearing loss ensues—or, in cases cited above, death.

There is no singular reason why this has happened, though the growing income divide is an obvious catalyst. Fewer people are doing more work for less pay as an elite few take more and more of the earnings. Many modern jobs provide no sense of meaning; if you feel easily replaceable your appreciation of the work will be nonexistent. Factor in the struggles of our health care system and, well, as Pfeffer says,

Job engagement, according to Gallup, is low. Distrust in management, according to the Edelman trust index, is high. Job satisfaction, according to the Conference Board, is low and has been in continual decline. The gig economy is growing, economic insecurity is growing, and wage growth overall has stagnated. Fewer people are covered by employer-sponsored health insurance than in the past, according to Kaiser Foundation surveys. And a strikingly high percentage of people, even those covered by insurance, say they forgo treatment and medications because of cost issues.

What makes this all the more confusing, he continues, is that workers know they’re suffering. One Amazon employee Pfeffer interviews is cognizant of the “chaotic organizational structure, political infighting, and a difficult boss whom she could never satisfy,” which resulted in her stomach aches, headaches, and skin rashes. To cope she started binge eating and binge drinking.

Pfeffer cites economics as the first reason many people persist in the jobs that are killing them. Beyond that, company prestige, challenging work, inertia, and pride are all attributed to keeping workers put. Leaving a position is a blow to self-esteem; some would rather “tough it out” than admit failure, even if in the process their health is sacrificed. This confusing paradox is made all the worse by its persistence across occupations.

What’s worse, this toxicity has become normalized. The human ego is both resilient and fragile, always ready to be swayed by popular opinion—Pfeffer points out that “norm” and “normative” generally play out similarly. While three general reasons exist for people leaving a job—a final, precipitating event; supportive family and friends; becoming so psychologically and/or physically sick they cannot continue—it often takes too long to muster the courage.

Pfeffer points to companies whose bottom line includes employee health, such as Barry-Wehmiller, Patagonia, Zillow, Collective Health, Google, and DaVita. In the manic demand for maximal productivity, most businesses fail to realize that they’ll lose more money—estimates are at $300 billion— when their employees are suffering from chronic stress. Calling out these “social polluters” arms workers and the public with a powerful tool for shaming executives and boards into making better decisions, a trend Pfeffer hopes will grow.

Good health, he notes, goes beyond the advertising fluff known as wellness programs offered during lunchtime or after work. He is quite clear these do not work:

Wellness programs are an attempt to remediate the harmful effects of what’s going on in the workplace. Instead of remediation you need to prevent. Instead of causing you to over-smoke and over-drink and over-eat and under-exercise because of what goes on in the workplace, and then giving you a wellness program, they should change the underlying work conditions.

Pfeffer foresees a future in which workplace stress is measured in the same way as pollution and workers sue companies like the tobacco industry was for creating deadly products. Laudable goals, certainly, but in a nation fraught with political tension and a growing gig economy, staring at a future with more automation and less secure employment, we’d better start such initiatives now.

—

Derek Beres is the author of Whole Motion and creator of Clarity: Anxiety Reduction for Optimal Health. Based in Los Angeles, he is working on a new book about spiritual consumerism. Stay in touch on Facebook and Twitter.