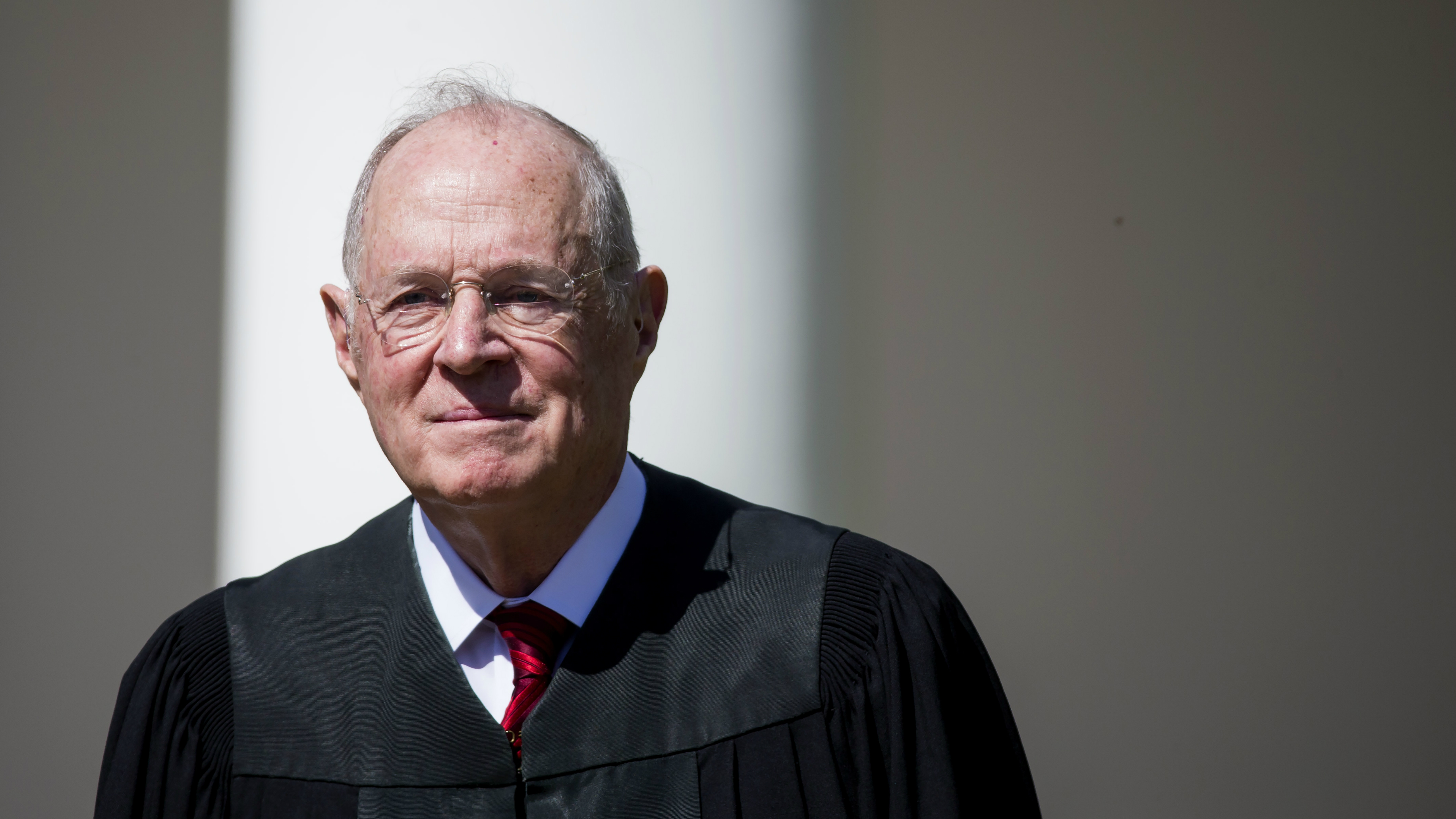

The Liberal Face of Justice Scalia

Antonin Scalia, a justice nicknamed “Nino”, is being portrayed as one of the Supreme Court’s staunchest conservative voices. Indeed he was: Justice Scalia authored a 5-4 opinion in 2008 declaring that the Second Amendment guarantees an individual’s right to bear arms. He was a dependably acerbic voice against gay rights, warning presciently in cases from 2003 and 2013 that the court was headed inexorably toward a ruling that would make same-sex marriage a constitutional right. He believed that Roe v. Wade, the 1973 ruling that established a right to abortion, was wrongly decided. He embraced capital punishment and took a skeptical view of the “separation of church and state,” regarding the division as phony and ungrounded in the constitutional text. And most notoriously, he supplied one of the five votes that made George W. Bush the nation’s 43rd president in the explosive caseBush v. Gore. (When people would complain about this in later years, he famously told them to “get over it.”)

But a more nuanced picture of Justice Scalia’s 30-year stint on the nation’s highest court tells a tale that complicates the conservative-mouthpiece narrative that has led to some very unsavory cheering of his demise on Twitter. For all of his apparent advocacy of far-right positions, Justice Scalia has written opinions that liberals have reason to cheer. And more importantly, his intellectual temperament reflects an openness to ideas that few ideological liberals seem to have these days.

Nino’s liberal jurisprudence

Perhaps the most notable case in which Justice Scalia voted contrary to his personal ideology was Texas v. Johnson, a 1989 ruling that struck down a law banning the burning of the American flag. Scalia was no flag-burner himself, of course, and he admitted to reviling people who desecrated this symbol of the American republic. But he refused to join either of the two dissents and voted with the Court’s liberal justices to hold that the First Amendment protects critics of the government who choose to express their disdain for the country by setting its flag aflame.

While Justice Scalia’s originalism made him an unswerving vote to uphold death-penalty laws (he liked to point out that the Constitution itself refers to capital punishment, so the Eighth Amendment cannot be understood to ban it), he voted time and time again on the side of criminal defendants. His vehicle for coming to their rescue was the Sixth Amendment, one of the more obscure harbors in the Bill of Rights that became more robust as a result of Justice Scalia’s advocacy. He pushed his fellow justices to take more seriously the guarantee of a jury trial and especially the so-called “Confrontation Clause,” a provision that requires criminal defendants to be faced (in person) by their accusers. A year ago, Justice Scalia took his frequent ally Justice Samuel Alito to task for “shoveling … fresh dirt upon the Sixth Amendment right of confrontation so recently rescued from the grave” in a decision Scalia had written in 2004.

One of the questions that will remain a mystery is how Justice Scalia would have voted in one of this term’s biggest cases: a challenge to the power of public-sector unions to charge non-members “agency fees” to facilitate collective bargaining. Justice Alito has been itching for years to abandon a 1970s-era Supreme Court precedent that permitted unions to charge non-members these fees for bargaining for their wages and benefits (but not for political advocacy). In the oral argument in Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association last month, Justice Scalia seemed to be edging toward Alito’s position that non-members have a right not to subsidize union speech. But in a previous ruling from 1991, he wrote that “where the state imposes upon the union a duty to deliver services it may permit the union to demand reimbursement from … nonunion members of the union’s own bargaining unit.” Justice Scalia was no ideological friend of organized labor, but the logic of his past rulings could conceivably have led him to be the unions’ savior this spring.

Nino’s penchant for engaging with rival views

The stereotypical conservative, in the eyes of liberals, is stuffy and closed-minded, set in his ways and allergic to ideas that differ from his. This caricature cannot be ascribed to Justice Scalia. In contrast to most of his brethren, who surround themselves with law clerks with roughly similar views about the law and politics, Justice Scalia went out of his way most years to hire one clerk who thought quite differently from him. The liberal clerk would help him wrestle with the opposing side of a case to enable him to fashion more deeply reasoned, more persuasive opinions.

David Axelrod, a former advisor to President Barack Obama, tells a remarkable story about how willing Justice Scalia was to entertain opposing viewpoints. When Obama was mulling over a successor for David Souter, who retired in 2009, Scalia offered some surprising advice: “’Let me put a finer point on it,’ the justice said, in a lower, purposeful tone of voice, his eyes fixed on mine. ‘I hope he sends us Elena Kagan.’” Sonia Sotomayor got the nod from Obama that year, but when another seat opened up, he did indeed choose Elena Kagan, an Obama solicitor general and strong liberal voice. Axelrod writes, “I was surprised that a member of the court would so bluntly propose a nominee, and intrigued that it was Kagan, the former Harvard Law School dean who was appointed solicitor general by Obama to represent the government before the Supreme Court. Though she had worked on policy in the Clinton administration and had a reputation for pragmatism, Kagan plainly would be a liberal in the context of the court. … Each was a graduate of Harvard Law School and had taught at the University of Chicago Law School, though in different eras. They were of different generations, he the son of an Italian immigrant, she a Jew from New York City’s left-leaning West Side. But they shared an intellectual rigor and a robust sense of humor. And if Scalia could not have a philosophical ally in the next court appointee, he had hoped, at least, for one with the heft to give him a good, honest fight.”

This integrity and pugnacious spirit is captured poignantly by another liberal justice, the redoubtable Ruth Bader Ginsburg, his ideological opponent and “best buddy”:

“Toward the end of the opera Scalia/Ginsburg, tenor Scalia and soprano Ginsburg sing a duet: ‘We are different; we are one,’ different in our interpretation of written texts, one in our reverence for the Constitution and the institution we serve.

From our years together at the D.C. Circuit, we were best buddies. We disagreed now and then, but when I wrote for the Court and received a Scalia dissent, the opinion ultimately released was notably better than my initial circulation.

Justice Scalia nailed all the weak spots — the ‘applesauce’ and ‘argle bargle’—and gave me just what I needed to strengthen the majority opinion. He was a jurist of captivating brilliance and wit, with a rare talent to make even the most sober judge laugh.”

The bottom line

Just as Justice Scalia sought out great legal minds to argue with him and sharpen his arguments, it behooves Americans who disagreed with him vehemently on any number of issues to learn from his example. Democracy is not well conducted by citizens who demonize their political opponents and feed their minds exclusively with ideas they already have by consulting news sources, blogs, and talk shows that massage preconceived views. Much better, the example of Justice Scalia shows, to listen, argue, and engage while respecting your interlocutor.

—

Steven V. Mazie is Professor of Political Studies at Bard High School Early College-Manhattan and Supreme Court correspondent for The Economist. He holds an A.B. in Government from Harvard College and a Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of Michigan. He is author, most recently, of American Justice 2015: The Dramatic Tenth Term of the Roberts Court.

Image credit: shutterstock.com

Follow Steven Mazie on Twitter: @stevenmazie