The Persistence of Memory: Christian Boltanski and Memory

In an exhibition currently at the Park Avenue Armory in New York City, a crane reaches into a mountain of clothes and pulls out at random a selection of shirts, pants, etc., only to release them to flutter back to their brethren. “No Man’s Land,” Christian Boltanski’s latest art installation, moves to the soundtrack of a thousand human heartbeats. The uninhabited clothing recalls the Holocaust, and Boltanski’s invites that connection. Memory, both personal and cultural, pervades all his work. A new monograph on the artist examines Boltanski’s career and the persistence of memory in both playful and humorous as well as dark and disturbing ways.

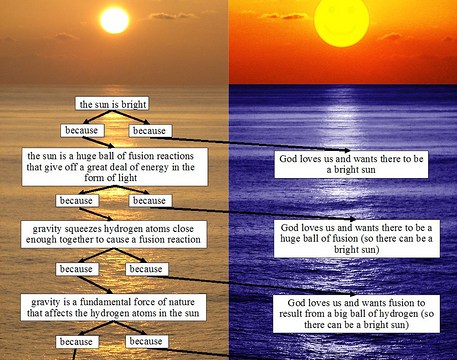

“There’s a story,” Catherine Grenier, director of contemporary collections at the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris, titles her essay on Boltanski. Whenever called upon for an explanation of his art, Boltanski famously replies with a favorite story. Grenier sees this narrative impulse as one of Boltanski’s “profound beliefs”: “the sole condition for the existence of reality is fable (i.e. storytelling), since narrative is its only means of transmission.” In other words, we can never touch some pure form of the elusive concept of “reality”; instead, we are left only with the stories we tell to transmit that concept of reality.

Many early works of Boltanski’s construct a personal fable of autobiography through minutiae. These “inventories” of personal objects project the illusion of obsessive individual detail, but the items themselves are bogus, clearly unlikely to belong to Boltanski the artist’s past. “In subjecting such contemporary and nondescript material to a treatment usually reserved for the ancient or exotic,” Grenier argues, “the artist reaffirms the ridiculous and pointless nature of the biographical project.” But, if biography is always absurd, and therefore pointless, what is the point of self-examination and self-commemoration, either of the individual or the masses?

Boltanski often recreates fables of childhood in his work. Childhood, in his hands is “the bedrock of humanity” that “defuse[s] all nihilism,” Grenier believes. “For Boltanski,” she continues, “the crucial importance of childhood and a belief in the redeeming power of memory constitute an antidote to despair.” In the end, memory persists because we know that the opposite of memory is not forgetting but, rather, despair over the void of storylessness. Boltanski asks the big questions that the art of Duchamp often asked, while also asking the small questions set in miniature that the art of Cornell often asked. Duchamp played like a child with reality, while Cornell preserved the childlike in his precious boxes, but Boltanski both plays and preserves childhood to make use of it as a panacea for the modern condition. Boltanski becomes the last romantic holding onto the idea of childhood “trailing clouds of glory,” and hopes that those fleeting glimpses are enough to keep us sane into old age.

“The artist is somebody who has a mirror in the place of a face,” Boltanski once said, “and each time somebody sees it, he says ‘that’s me.’” When you read this monograph and ponder the generous offering of images from every stage of Boltanski’s career, you can’t help but see these false autobiographies and think, “That’s me.” Boltanski’s story compels to tell our stories, if only to ourselves. The persistence of memory allows us to persist despite the long odds against the erasure of the self in the vast, empty void of modern life post-Holocaust. A glimpse into this monograph and the work of Boltanski is a glipse into a mirror upon which we should long reflect.

[Many thanks to Rizzoli USA for providing me with a review copy of Christian Boltanski.]