Wild Animal Performances: Unsafe For Us, Unhappy For Them

The circus seems like a fading relic from a simpler time, but if you’re like me, and grew up in a rural area, you understand why it’s still around. Traveling circuses are willing to go places that typically don’t end up with much in the way of live entertainment, performing shows at country fairgrounds and small high-school gymnasiums. I first went to the circus when I was six years old, and the headliner (who knew circuses could have a headliner?) was some BMX rider. There were also trapeze artists, clowns, and probably some dogs. I don’t really remember, because it was a long time ago, and I was probably more interested in my box of popcorn than anything else.

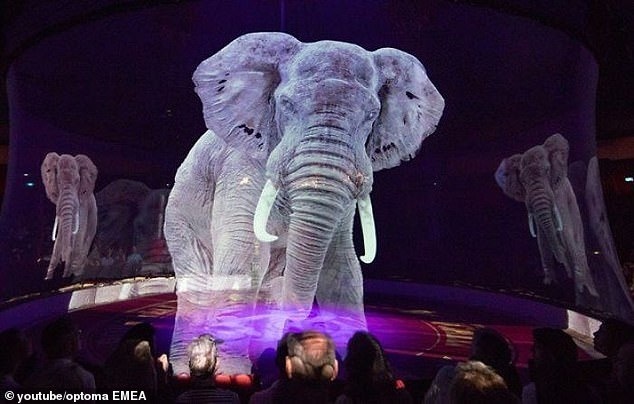

The circus that came to my town was too small to have elephants, the animal that is associated with circus performances more than any other. I don’t remember being particularly disappointed by this, nor did I expect that a circus must have elephants. Knowing what I know now, it’s a good thing that there weren’t any. Just a few years before, there was a fatal incident with an escaped circus elephant that should’ve raised a huge red flag, and is just now starting to draw attention, thanks to the documentary Tyke Elephant Outlaw.

On August 20, 1994, Tyke, a 21-year-old female elephant that performed with Circus International, became out of control during a performance in Honolulu. Tyke trampled her handler, killed her trainer, and then got loose in the streets of Hawaii. Remarkably, no one else was killed, but nine bystanders were injured as a result of the incident. Tyke’s rampage ended after she was shot 86 times by police and civilians.

For those who have seen the film Blackfish, many plot details will sound familiar. Just like the killer whale at the center of that film, Tyke the elephant had previously been aggressive and defiant. At a show in Altoona, Pennsylvania, in April of 1993, she broke loose from her handler and escaped to a balcony, causing $14,000 of damage in the process. Three months later, at a fair in North Dakota, she once again ran unrestrained amongst fairgoers for over 20 minutes. Numerous elephant trainers advised their colleagues not to bring Tyke on the road to Honolulu, but the elephants’ handlers and owners did not want to alter their show.

The directors of Tyke Elephant Outlaw, Susan Lambert and Stefan Moore, have said that they did not intend to make an animal-rights film. And while I’m somewhere between apathetic and dismissive when it comes to animal-rights issues, the film, like Blackfish before it, methodically lays out compelling reasons why society should move on from performances by wild animals. Threats to spectator safety are rare but real, because animals trained in cruel conditions are prone to acting out. Not much of cultural or artistic value is lost by scrapping wild-animal performances; animals’ “show behaviors” bear little resemblance to how they act in the wild. And circuses could still continue, utilizing domesticated animals and human acts.

Since Tyke’s fatal escape, 20 countries have passed laws banning wild animals from performing. Even without passing any laws, Honolulu has not hosted a similar performance since Tyke left her mark on the city. Ringling Brothers announced its plans to phase out elephants and other wild animals by the year 2020. Whether or not animal-rights activists succeed in their legislative efforts, cultural forces like Tyke Elephant Outlaw are paving the way for safer, more humane circuses.

For more, visit the film’s website, and check out this video from artist Fritz Haeg on the Animal Estate project: