Artistic License: Do We Know It When We See It?

Dani Shapiro’s recent New York Times editorial was not the first shot fired in the never-ending debate about the limits of artistic license, but it is one of the most powerful. As the Larry Rivers Daughters Videos story develops, and as Roman Polanski exits house arrest and thanks the Swiss government for his freedom, Shapiro’s reflections remind us that in the case of artists who celebrate or manipulate (depending on your point of view) their subjects, history does not “repeat” itself “first as tragedy and then as farce,” but rather simply repeats itself, full-stop. There is shock and pain and art; there is shock and pain and art. Enforceable change in these cases seems slightly out of society’s reach.

“Artistic license” is most often associated with subtle, if controversial, changes artists make from what others consider fact, or traditional. Yet the transgressions Polanski and Rivers are accused of also fall, for some observers (and almost all parents), into this category, too. It is artistic illicense. Polanski was taking pictures of the young girl he was accused of abusing. She was thirteen. Rivers made videos of his naked daughters. They were also teenagers. These are only two examples but they seem familiar, reliable clichés of what we expect—not only from artists—from people. There is no line in the sand for artists, is there?

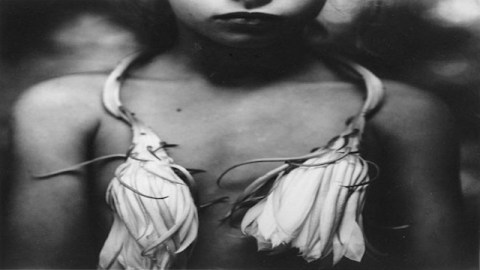

Here is another case. The photographer Sally Mann, referenced by Shapiro in her piece (and also the inspiration for a character in one of Shapiro’s novels) is an extraordinary artist. Yet Mann’s work was criticized; her photographs of her exceptionally beautiful children were considered exploitative. There was no challenge of sexual misconduct in her case; still, people felt an artist’s child should be protected from her—in her case, literally speaking—lens. We know the price of accepting this line: we would lose the art. And in Mann’s case, this would have been a hard loss to bear.

So perhaps “artistic license” is not the best phrase. Because we can say there is artistic responsibility, and parental responsibility, and common decency. These are things that cannot be narrowly defined, nor policed. They must, as Justice Potter Stewart said of pornography, be known when we see them, which is to say, when we feel them—in ourselves and in others. Shapiro implies that returning Rivers work to his daughter is right, and redemptive. In that case, this seems inarguably true; Rivers’ videos are held by NYU, and they can be returned to the subject, and they are notThe Mona Lisa. But the Mann images pose a more complex question: would collectors who own them elect to release them? They are sublime; they are universal; they remind us of the wondrous, risk-littered nature of being a child. In the end, does it come down to, if the art is worth it, further license is granted?