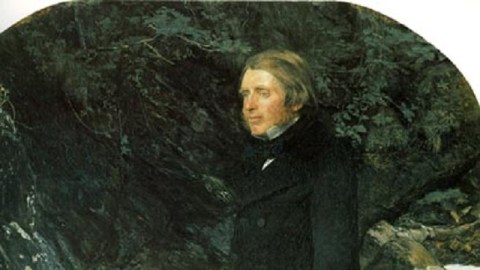

Can We Still See Nature Through John Ruskin’s Eyes?

“If you’ve just had a bad week at the office,” suggests Keith Broomfield in a recent article in The Scotsman, “then spare a thought for 19th-century artist John Everett Millais whose famous painting of the art critic and social commentator John Ruskin is now being celebrated by a new trail in the Trossachs.” For 140 years, the exact spot where Millais and Ruskin stood to make the painting was lost, but now anyone can find inspiration at that intersection of trail and waterfall. However, can simply standing where Ruskin stood and looking upon nature cure “a bad week at the office”? From the perspective of 2011, can we still see nature through John Ruskin’s Victorian, “Last Romantic” eyes?

As Broomfield explains, Alastair Grieve rediscovered the painting’s scene in 1993. Woodland Trust Scotland, the organization that owns and manages Glen Finglas, the area of Scotland Ruskin and Millais traveled to in 1853, finally shaped a trail to that remote location so that fans of the painting (and nature in general) could have the “Ruskin experience.” One can only hope that visitors don’t have the full Ruskin experience, since the critic lost his wife to the man who painted him beginning with that time in the Trossachs. Millais actually finished the painting in his studio a year later, after Ruskin’s marriage to Effie ended and Millais’ life with her was set to begin. The chill in the studio between painter and model must have been greater than even a night in the Scottish Highlands.

But what is this restorative “Ruskin experience” really? “Nature never did betray/ The heart that loved her,” William Wordsworth wrote in “Tintern Abbey.” Ruskin took those words to heart, believing that nature would save the world, specifically in arts that mimicked and celebrated nature through close observation. My first “Ruskin experience” came when I read the critic’s 1843 book Modern Painters, Ruskin’s defense of the groundbreaking painting of J. M. W. Turner and the work that put Ruskin on the cultural map. I found myself unable to look at rocks or clouds or moving water in the same way after reading Ruskin. Millais’ portrait captures this aspect of Ruskin’s approach beautifully by placing him (rather awkwardly, in formal dress) on his beloved rocks with green foliage and a roaring waterfall behind him.

But can we ever recover the Wordsworthian/Ruskian vision? Post-Romanticism now verges on anti-Romanticism in this “Age of Terror.” It’s hard to look at even a pure blue sky and feel a connection to unadulterated goodness, at least without some kind of religious affiliation. My favorite anti-Romantic sound bite comes in Werner Herzog’s 2005 documentary Grizzly Man, which used the documentary footage of Timothy Treadwell, who lived in the wild with grizzly bears until they brutally killed him. “And what haunts me,” Herzog says in the narration to Treadwell’s own film footage, “is that in all the faces of all the bears that Treadwell ever filmed, I discover no kinship, no understanding, no mercy. I see only the overwhelming indifference of nature. To me, there is no such thing as a secret world of the bears. And this blank stare speaks only of a half-bored interest in food. But for Timothy Treadwell, this bear was a friend, a savior.” Ruskin, like Treadwell and like those who may search for the painting’s origin, saw a savior in nature. Ruskin’s greatest physical danger may have been slippery rocks instead of grizzlies, but the real danger may have been a misplaced faith in a nature-based salvation. As much as Ruskin understood nature, nature would never “understand” him back.

A Pre-Raphaelite theme park of sorts in remote Scotland with connections to the Ruskin-Millais-Gray love triangle sounds like a great place for art fans and hikers to go. For those looking for a restorative experience in nature, they may want to look elsewhere. If Ruskin himself were alive, I doubt he would go back.

[Image: John Everett Millais. John Ruskin (detail), 1853-1854.]