Chinese Mothers, American Anxieties and the Nature of Parenting

Over the weekend I read Amy Chua’s paean to “Chinese parents” in The Wall Street Journal with morbid fascination. What felt morbid was Chua’s “Mommie Dearest” anecdote about battling with her 7-year-old because the little girl couldn’t master a difficult piano piece (which involved threatening to toss the child’s toys, working through dinner with no bathroom breaks, calling her daughter lazy and pathetic etc.) The fascination stemmed from the undeniable truth of Chua’s justification: “Nothing is fun until you’re good at it.”

That’s the heart of the “Chinese parent” philosophy that Chua describes in her new book, which the Journal excerpted. (I put “Chinese parent” in quotes because, as Chua writes, she’s describing an attitude toward child-rearing, not an approach unique to China.) “To get good at anything,” she writes, “you have to work, and children on their own never want to work, which is why it is crucial to override their preferences.” Hence her “war zone” approach to piano practice, and her rules for her two daughters, which included no sleepovers, no playdates, no television, no school plays and no grades less than an A. The way to deal with “substandard performance”? “Excoriate, punish and shame the child.”

There’s no news in Chua’s description of the “Chinese parent” model and its many differences from middle-class American conventions. That American parents praise where East Asian parents would use shame has been well documented (the anthropologist Naomi Quinn discusses many such studies here), as has the Asian parents’ stress on achievement over fun (pdf). It’s not exactly a secret out on the street, either.

There are things that all parents do in raising children (these are the subject of Quinn’s very interesting paper). But those universals aren’t to be found in particular practices about rules, self-expression, playtime or the like. There, what you find is cultural variety. There, as Quinn writes, anthropologists have documented that the Dutch make their babies sleep hours more than do Americans, that Gusii mothers in western Kenya strongly discourage babies’ eye contact, that residents of Ifaluk in the Pacific Ocean are appalled by a happy kid (glee is supposed to lead children to fall off cliffs or drown in lagoons). But anthropologists speak with studious, isn’t-that-interesting, it-takes-all-kinds neutrality. Chua wants none of that; she declares that the Chinese way is best (at least, if you want successful and accomplished children), hence the Journal’s headline: “Why Chinese Mothers Are Superior.” That’s novel.

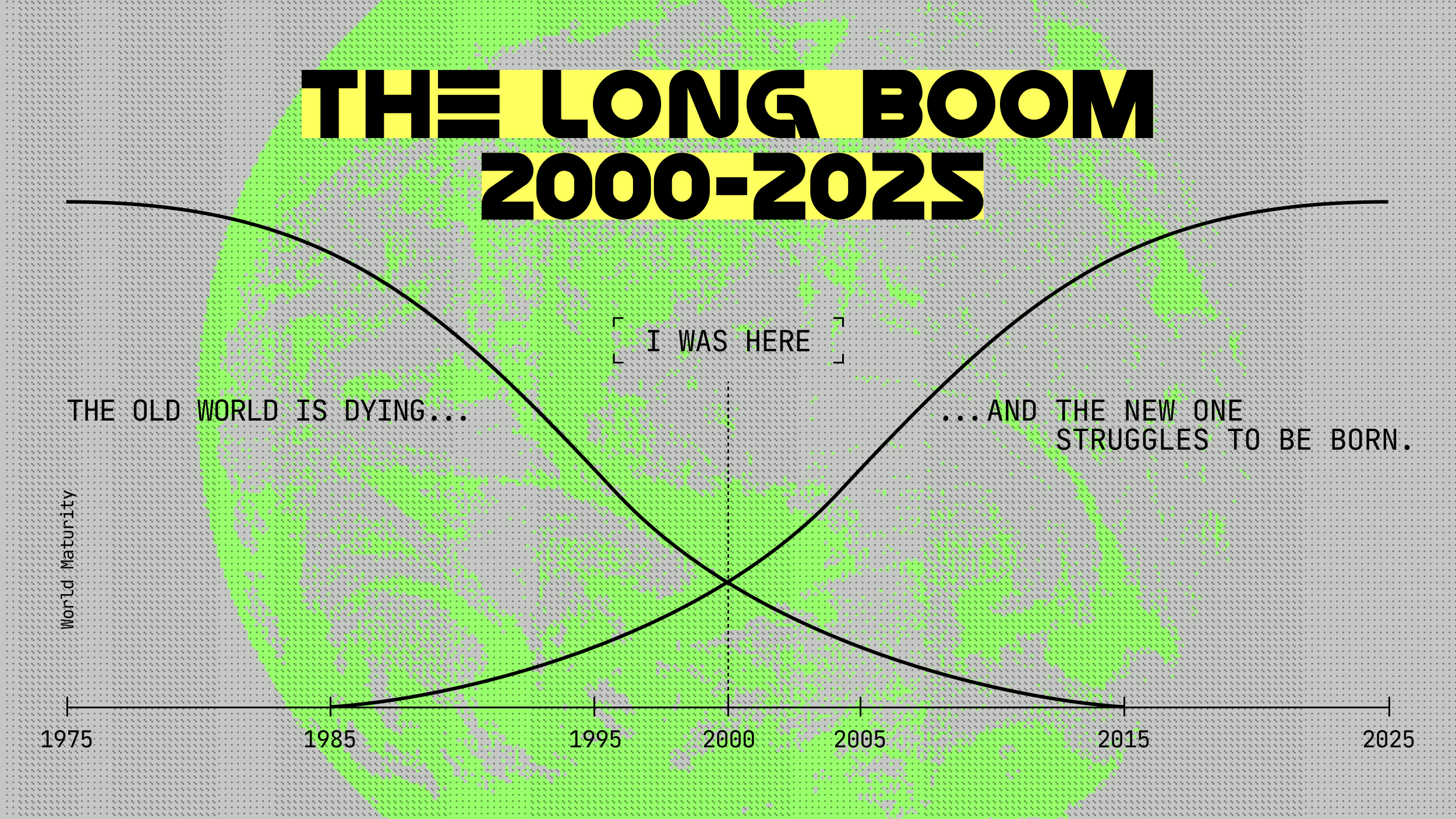

So too is American receptiveness, in 2011, to being told how other people are better at life than we are. This is an imperial mood-swing that has happened before, to the United States and to other global powers. Empires tend to look over their shoulders, wondering who is going to overtake them. In the 1980s, it was a pop-culture commonplace that the world would soon be run by Japan (so in Back to the Future 2, Marty McFly’s boss in 2015 is a Mr. Fujitsu). Today the Chinese have replaced their neighbors in Americans’ nightmares of decline. But the anxious rhetoric is the same: We’ve gone soft, while over there they’re working harder, smarter and better.

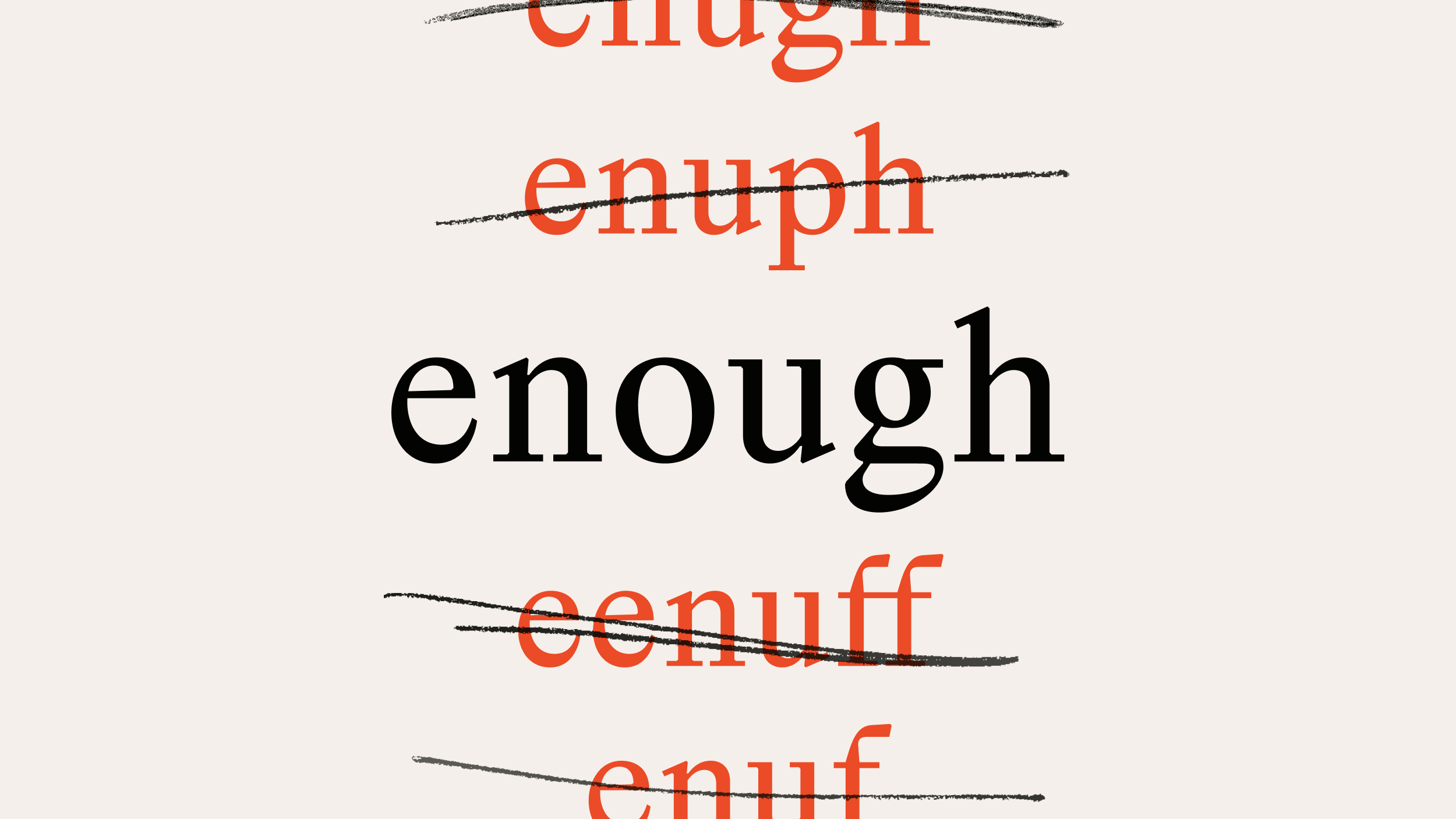

This mood doesn’t mean that the content of Chua’s criticisms is wrong. She hates the attitude she calls “everyone is special in their special own way,” or, “even losers are special in their own special way.” That praise and acceptance should be connected to actual achievements isn’t a new idea either (check out the top of this page for an example from 1984) but Chua is right to note that in America it struggles against a culture of bland reassurance. That culture pushes Americans to look at the surface meaning of what they say to kids, not the context: to ask “was the kid made to feel bad?” rather than “why was the kid made to feel bad?”

That’s a dead end. “Nothing is fun until you’re good at it,” after all. (Isn’t it strange, though, to read this message on the very conservative Wall Street Journal Op-Ed page? After all, what is American conservatism in 2011 but a toddlerish temper tantrum? “Don’t wanna pay more taxes! Don’t wanna do anything about global warming! Don’t wanna eat different than before! You can’t make me!” Sound health care and sustainable economics won’t be fun, either, until we are good at them.)

Point is, the path to feeling good, as a competent person, begins by feeling bad that you aren’t there yet. That is one of the universals that Quinn finds in her theory of parenting.

Be you a Chinese parent who makes their kids practice instruments 3 hours a day, or a German who has them wait for a “WALK” sign even when there are no cars coming, or a Gusii who makes sure they never converse eye-to-eye, you will, Quinn says, do three things. First, you’ll engineer their experiences so that the lessons are consistent (ie, not practicing the piano is never OK); second, you will accompany your teaching with strong emotion (not all of them pleasant). And third, you will make clear that getting it right is “good” while screwing up is “bad.”

Chua’s daughter shredded the score of her piano piece (Chua just taped it back together) and the house turned into a “war zone,” but, in the end, her mother writes, she learned the piece at last. And at least (big grain of salt here) according to her mother, was delighted by her achievement.

That suggests to me that the fundamentals of the relationship between mother and daughter have nothing to do with household rules, but rather with how those rules are enforced. I’m sure there are monstrous Chinese parents (and China’s suicide rate suggests that there are pitfalls to the achievement-is-everything model). But, as Chua says, there are also monstrous “American-style” parents who say all the right things about their wonderful children’s perfection. How things are said counts for more than what.

QUINN, N. (2003). Cultural Selves Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1001 (1), 145-176 DOI: 10.1196/annals.1279.010![]()