Diplomacy Will Survive WikiLeaks

The WikiLeaks drama is only the latest in over a century of new technologies heralding the demise of professional diplomacy—yet such rumors always prove to be greatly exaggerated.

One defense comes from Roger Cohen of the New York Times who notes that the leaked cables reveal that American diplomats are, contrary to popular opinion and derision, in fact rather well-informed, articulate, and courageous. The nuance in the cables’ language implies that the kind of insights first-hand diplomacy provides cannot be substitute by the fleeting news dispatches of contemporary journalists. Others point out how banal the cables reveal modern-day diplomacy to be: indeed just journalism transmitted in capital letters.

But to debate whether or not the WikiLeaks saga spells the end of diplomacy is besides the point, for diplomacy, as the saying goes, is the second oldest profession. It has adapted to many technological revolutions and persists in perpetually modified form. More than two centuries ago, Thomas Jefferson mused, “For two years we have not heard from our ambassador in Spain; if we again do not hear from him this year, we should write him a letter.” When Lord Palmerston received the first diplomatic cable at Whitehall in the mid- nineteenth century, he proclaimed, “This is the end of diplomacy!” In the 1970s, Canadian premier Pierre Trudeau remarked that he could replace his entire foreign ministry with a subscription to The New York Times, whose correspondents presumably provided better information than embassy cables.

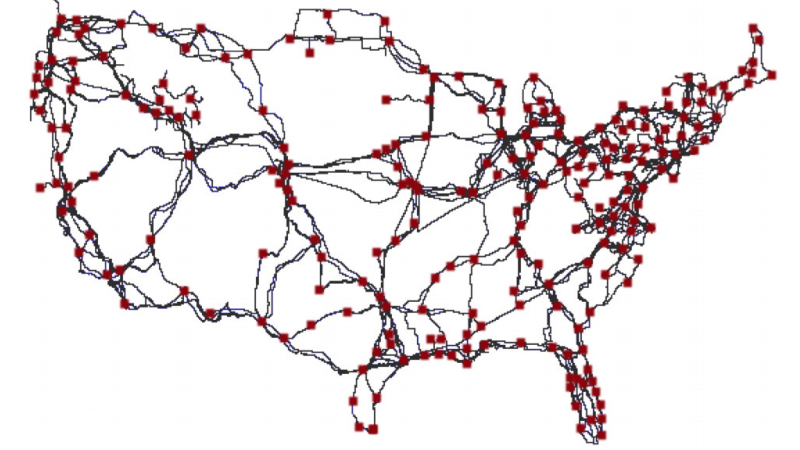

But diplomacy has survived competition from technology and the media much as journalism will survive beyond the print age as well. Indeed, cyberspace today is alive with virtual diplomacy: Sweden, Brazil, and other governments have opened virtual consulates in the universe of Second Life, where former U.S. undersecretary of state for public diplomacy James Glassman held debates with Egyptian bloggers. Senator John Kerry has even proposed the creation of an “ambassador for Cyberspace.” Now that Google and the U.S. Department of Defense’s research and development office DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) have pioneered handheld universal translation devices, everyone is a diplomat.

The who, what, when, where, why, and how of diplomacy have thus all been thrown into flux well before WikiLeaks. But as before, diplomacy will evolve, for we wouldn’t have a global system to speak of without it.

Ayesha and Parag Khanna explore human-technology co-evolution and its implications for society, business and politics at The Hybrid Reality Institute.