Do We Dream of Heroes? T.E. Lawrence, MP

There is often a fine line between hagiography and take down in the most artful examples of journalistic profile. The New Yorker’s seductive piece on politician-scholar-soldier-writer-potential future British Prime Minister Rory Stewart stands as the best latest example of the genre. What makes Ian Parker’s portrayal of Stewart so compelling, whether or not one has ever heard of (or been personally charmed by) Stewart, and whether or not one has ever seen the playing fields of Eton, is the delicate indecision the piece holds until the end about what the author thinks of his subject. Parker approached his subject with equal parts fascination and affront, and only at the end with something slyly closer to parody. Stewart will be immune to this treatment, even as his career arc begs anger and envy from his elite global classmates.

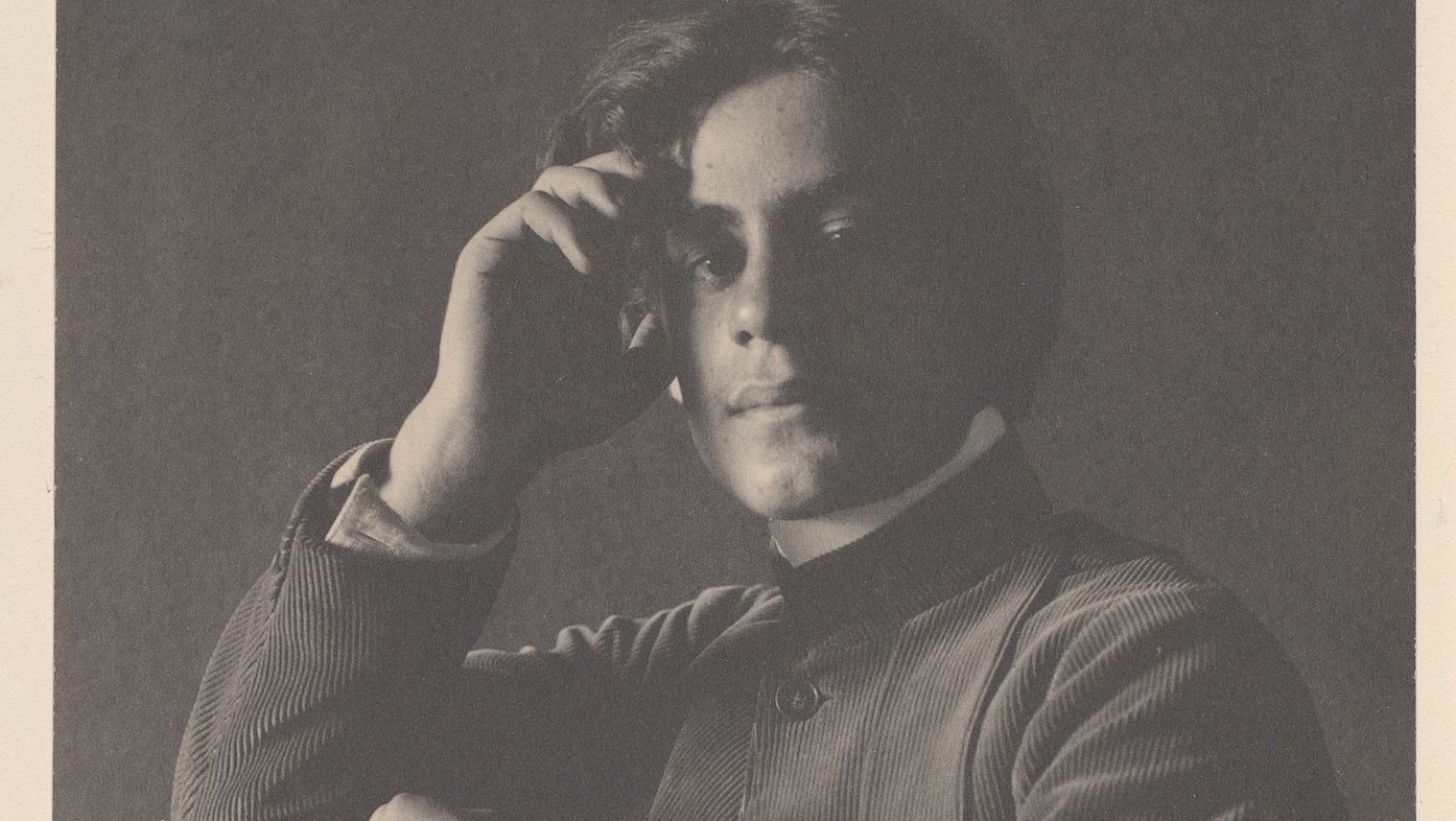

Stewart self-identifies with T.E. Lawrence. Lawrence, Lawrence of Arabia, was known not only for his writing but moreover because of his unique, never-wavering stance vis a vis his own place in the world, and the worth of someone like him. Which is to say: someone operating just enough outside the mainstream to gather anti-government/non-government interest, yet enough within the Main to be sure that the politicians read his work, and so would envy him. From the start, Stewart—like Lawrence—was marked for greatness, and Parker’s profile captures the nuances of his rise.

Parker quotes Stewart on the subject of heroes:

“We imagine, in the modern world, that heroes are accidental heroes. But, historically, many of the people who were heroes in their society set out to be heroes. They emulated other heroes, were obsessed with being a hero, wanted to be godlike. In contemporary society, that disqualifies you. If you’re trying to be a hero, you almost by definition can’t be. But Achilles wants to be a hero.”

And what’s wrong with heroes? Lawrence still catches the imagination of British schoolboys; is there an American corollary of this romance? The cliché of the English dream is that it is one about overcoming privilege, pursuing a need to show one’s peers that “intelligence” is the bravest form of action, one best placed post-military service and pre-time at 10 Downing Street. This dream is alive. (Any Etonian reading Parker’s piece will say, I know so many like this). But do American schoolchildren dream of being heroes? Is our Great Game still set firmly between the coasts? Will a future generation, born after this American Empire, stake broader claims to being “good soldiers” by spending more time abroad, more time believing that patriotism is not a dirty word?

The rise in ardor for Lawrence after England’s end of Empire might prove a lesson for Americans, and Stewart stands as a provocative example of this. He has had his romance. He has had his Harvard post. Now he is home to serve, and whether his mark will end up being legislative, geopolitical, academic—or all three—one cannot argue that he has already made one. Parker writes that Stewarts “longs to be more than an ordinary overachiever; he wants to be connected to the epic.” Is this a crime?