Down the Rabbit Hole: Finding ‘Evidence’ of WikiLeaks’ Crime—Part I of II

Today and tomorrow I’ll hopefully make peace with my curiosity about WikiLeaks and the accusation that it disclosed the names and locations of Afghan informants serving the U.S. and coalition forces. Evidence supporting the accusation has been scant while the accusation itself has been repeated so often it now has the force of truth. Where does the accusation come from? What implications does the evidence entail? I will answer these questions today and tomorrow.

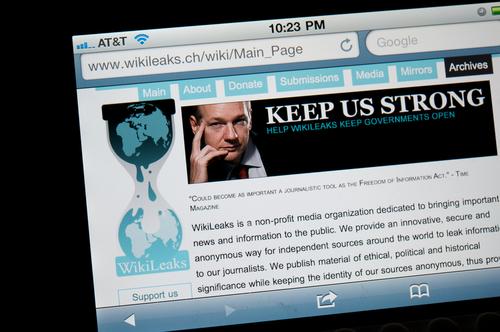

Raffi Khatchadourian of the New Yorker may be the world’s foremost authority on WikiLeaks seeing as he conducted extensive interviews with its leader, Julian Assange, and other members of the group shortly before its now infamous release of six years worth of secret on-the-ground reporting from Afghanistan. Khatchadourian’s summary of WikiLeaks as an Internetstartup in this podcast better explains its actions than those who conversely call it a defender of truth or a terrorist organization. Assange acts to a high degree on principle, but seeing WikiLeaks as a startup explains why it threw caution to the wind, admitting that it did not examine the released documents thoroughly enough to rule out the possibility of releasing personal information that could be used against Americans and their allies in the war effort. As a startup, they are tuning their operation, which is young and by no means perfect.

To be sure, this is more ‘with us or against us’ criticism. Neither Assange nor WikiLeaks are wedded to the achievement of that nebulous, ever changing justification for military action: securing the interests of the United States. In as much as the U.S. would punish one of its citizens for treason should it inform an enemy about U.S. war strategy or personnel, the American military and intelligence apparatus pay cash for Afghans to turn coat.

But more to the point: did WikiLeaks release information that put America and its allies in harm’s way? Every major American news organization has operated on that very assumption in its condemnation of the leak. After my post suggesting there was no concrete evidence of such a crime, I nervously checked WikiPedia’s page on ‘The Afghan War Diary’ thinking I had missed something obvious. The first thing you see when you scroll down to ‘Informants Named’ is ‘This section’s citation style may be unclear.’ The section’s citations are very unclear and quotations in the entry are rarely present in the citation referred to, though the accusation is repeated several times in the entry as fact. Oh well. Maybe my college professors weren’t just justifying their paycheck when they warned against citing WikiPedia.

Finally, all the ‘proof’ that WikiLeaks has blood on its hands, such as that presented by NBC, refers to two articles written in The Times of London:

Afghan leaks expose the identities of informants

Man named by WikiLeaks ‘war logs’ already dead

If you’ve got a subscription to The Times of London, which has recently put all its content behind a paywall, you’ll see that it claims that after only two hours of examining the Afghan war logs the newspaper found multiple cases where informant names had been disclosed. If you haven’t got a subscription, sorry, but you’re not privy to review the information that everyone else is claiming as proof positive of wrong doing. The culture of free that now exists around news and news producers poses a serious, albeit principled, democratic problem. If everyone expects news to be free, what happens when a news organization releases exclusive news from behind a paywall? I’m sure the news producer, The Times of London in this case, would like you to pay to read the story. But what about the millions that aren’t going to do that? After The Times put up its paywall, it lost 90% of its traffic. This allows exclusive information to selectively enter the mainstream news cycle, repeated by sources like NBC, but remain immune to democratic criticism. I think people should buy a subscription (I did), but the culture of free has, to an extent, restricted the flow of certain information in a dangerous way. For all our talk of citizen journalism, we are no longer accustomed to reviewing sources that we have to pay for. Journalism isn’t just recording events, after all. It’s getting the events right.