Fairy Princess: The Photography of Mika Ninagawa

When Japanese photographer Daido Moriyama, who works primarily in black and white, encountered a photograph by Mika Ninagawa of Technicolor flowers in close-up during a tour of a museum, he called it “an indubitable work of visual scandal—an assault—that drew a clandestine smile upon my face.” Like looking too long at the sun, peering too long at the images of Ninagawa can blind you, but with pure color rather than pure light. In a new monograph from Rizzoli of Ninagawa’s work, titled simply Mika Ninagawa, you find yourself first assaulted then smiling like Moriyama—plunged into a fantasy land resembling ours but amplified by color and imagination. Ninagawa reigns both as princess and queen in this fantasy land—a fairy princess granting our every wish for beauty in the world, while simultaneously a queen of the damned who understand the fragility of that beauty and cherish every fleeting moment.

“I like dark shadows, along with colors almost too bright and dazzling that I could go blind,” Ninagawa says in an interview reproduced in the book. “Generally, my photos turn out excellent when I take them in extreme heat, so hot that my head is spinning and I want to take shelter in my own shadow.” That fever pitch comes across in every acidic and flaming color. In addition to the impact of each individual image stands the cumulative effect of her work as presented in a book. Ninagawa loves arranging her works into books. “I like that a book has a tangible form and that people can own it,” she says in the same interview. “I enjoy the process of making books, even though it can be a struggle… When I make my books, I sometimes plan it in a logical manner, but in the end, what matters are my own feelings. The process starts with a gorgeous sense of euphoria, but it gets mellow towards the end, and finally, a crisp finale!” That “process” from euphoria to mellowness to crispness sounds much like a wine tasting, and Ninagawa’s photography intoxicates much like a wine, but a fruity, complex vintage that offers surprising complexity after the initial impression.

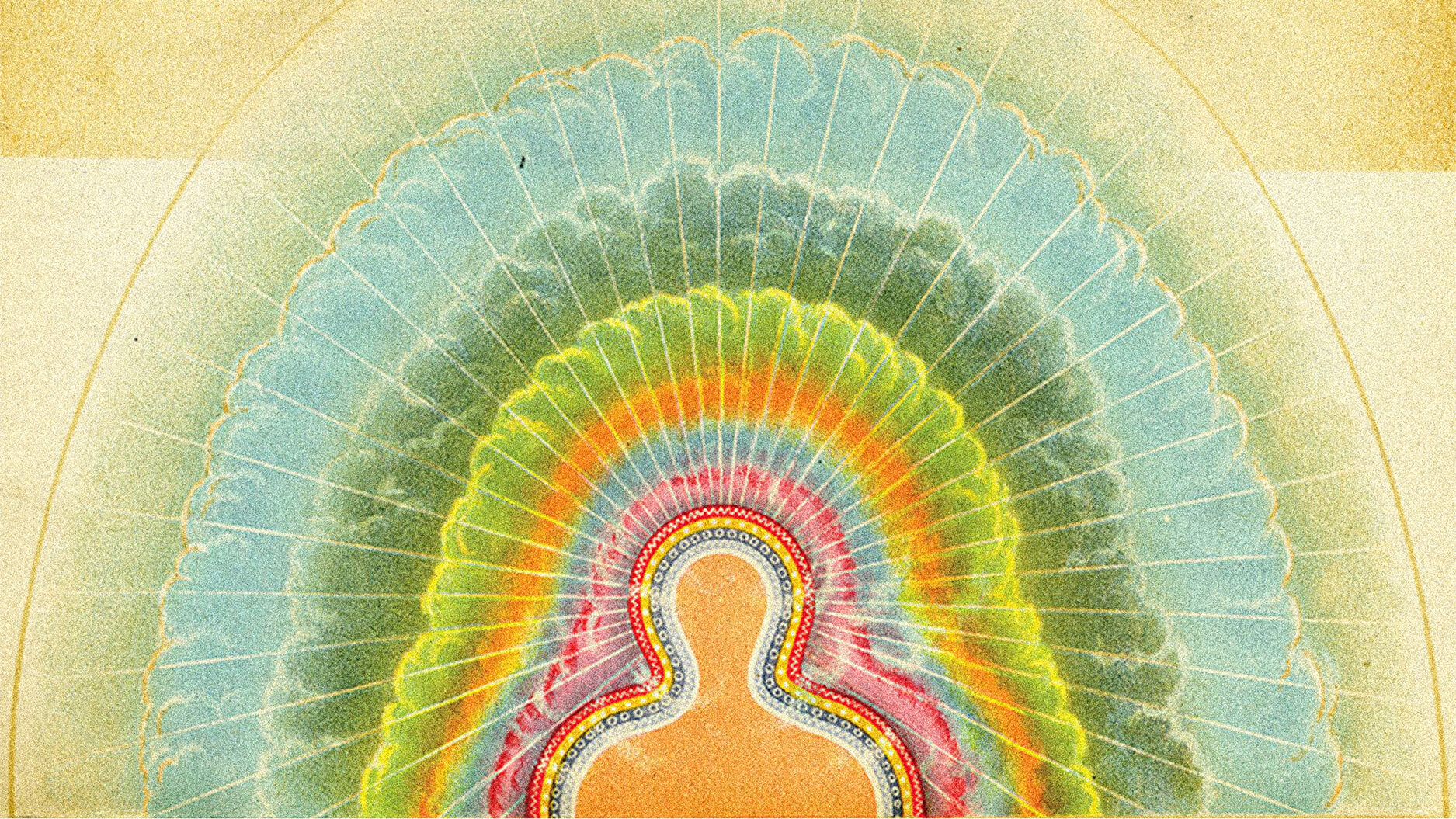

In “Earthly Flowers, Heavenly Colors: The Aesthetic Universe of Mika Ninagawa” art critic Midori Matsui tries to give some critical context to Ninagawa’s work. “In spite of surface artificiality, Ninagawa’s photographs powerfully convey the fullness of life,” Matsui suggests. “Her individual photos unabashedly celebrate the autonomous beauty of flowers blossoming regardless of human will, or the healthy narcissism of young people innocently absorbed in their own beauty, taking an unusual perspective that seems to annihilate distance with its objects by completely identifying with them.” In this age of irrepressible irony, Ninagawa takes beautiful pictures seriously, without a hint of sarcasm or sneering. Each photo celebrates life and beauty uninhibitedly. What on the surface seem to be fashion photos of celebrities, close ups of flowers, or studies of goldfish become almost prayers to a god of beauty and an evangelical force for us to pray along. Matsui sees this quality of Ninagawa’s photography as a modern updating of the Baroque impulse to capture the overflowing life force of nature as a reflection of its creator and the universality of all life. Ninagawa brings the Baroque back to the future by making full use of the modern format of photography.

Beneath that life-affirming veneer (or maybe beside it), always remains the acknowledgment of death. Moriyama’s “clandestine smile” in the gallery came from a mental comparison of Ninagawa’s flowers to Andy Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe. “Whenever I behold Mika Ninagawa’s work,” Moriyama explained, “I am overcome at once with an image of a transient sign of darkness that threatens a flawless midday sky, and a contrasting sense of beautiful fragility.” Matsui echoes Moriyama when she writes, “Ninagawa’s sensitivity to the ephemerality of life… paradoxically moves her to undertake an uncompromising quest for the expression of the abundance and beauty of life.” Curiously, the deeper Ninagawa delves into the life of things, the more conscious we become of the opposite power—death. Ninagawa sees the universe in a single flower filmed in extreme close up. The effect is much like that of Georgia O’Keeffe’s flower paintings—a combination of thanatos and eros—but where O’Keeffe worked in subtle shades, Ninagawa turns the dial to eleven and rages against the dying of the light with more and more light and color.

It’s this transformative power of the simplest subjects that makes Ninagawa’s work fascinating. A photograph of Japanese actress and model Chiaki Kuriyama titled Princess (shown above) actually elevates the modern celebrity to the status of fairy princess of a magical land of the mind. Matusi calls this transformation part of Ninagawa’s “Pop subversion of cultural hierarchy,” which includes not only princesses, but also “young actors of independent films as costumed characters” ready to play the role of romantic hero. What makes the prince and princess photos even more interesting is how Ninagawa uses background details and textures (often borrowing from traditional Japanese motifs) to connect people to natural elements such as flower petals and fish scales. The heterogeneity of the world before our everyday eyes becomes a homogenous universality through Ninagawa’s lens. Every corner of the world is magic, Ninagawa’s photos suggest, if we only look for it.

Ninagawa first rose to prominence in the art world as part of the “Girl Power” movement of the 1990s in Japan. Along with several other women artists, Ninagawa proved that women had something significant to offer to traditionally patriarchal Japanese culture. Mika Ninagawa proves that Ninagawa’s “Girl Power” still burns brightly to illuminate a new perspective through photography on the old, Baroque idea that this world is as colorful and alive as our imaginations allow it to be.

[Image:Mika Ninagawa photograph of Chiaki Kuriyama, aka, Princess.]

[Many thanks to Rizzoli for providing me with the image above and a review copy of Mika Ninagawa.]