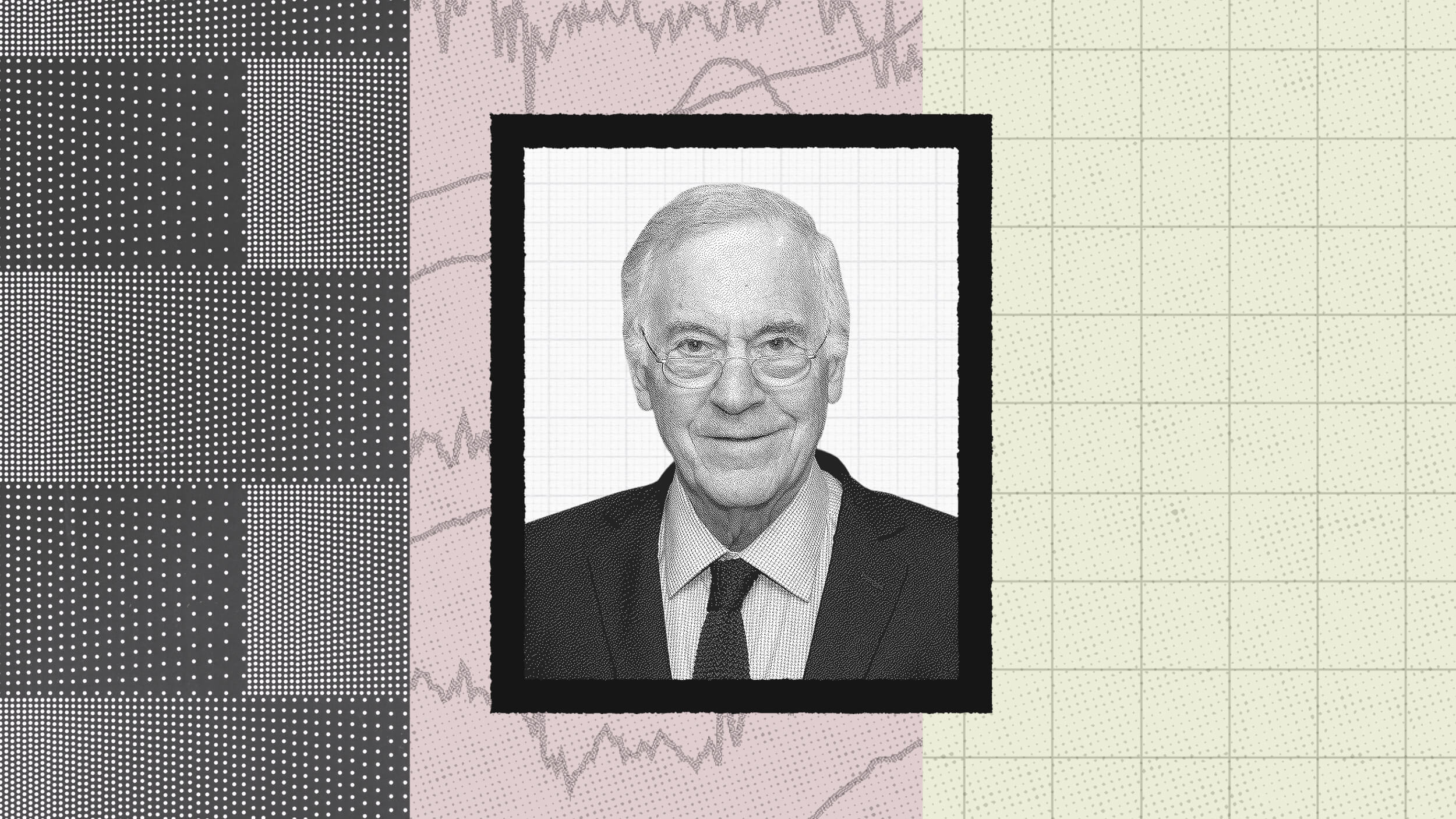

How Daniel Bell Predicted the Rise of Tea Party Conservatism and the Need for a New Public Philosophy

At the newly launched Breakthrough Journal, sociologist Fred Block re-visits Daniel Bell’s classic work The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism providing insight on the rise of Tea Party conservatism, the revolt against taxes, and in response, the need for a new public philosophy. The article merits a careful and thorough read. Below are a few highlights.

Here’s how Block describes the origins of Tea Party conservatism through the lens of Bell:

What is distinctive about Bell’s argument is that he identifies the critical problem as occurring at the level of culture or public philosophy. Many Americans today do not see why they need to turn over a substantial share of their earnings to the public sector. People often willingly give to a charity of their choosing, but they recoil at the idea of paying taxes to the government. Ardent Christians may acknowledge they are their “brothers’ keepers” and give to their churches every Sunday, but they insist on a fundamental moral distinction between tithing to a church and taxation. The former is legitimate because it is the result of a compact between the individual and a deity; the action has been freely chosen by a sovereign individual. Taxation, on the other hand, depends on coercion and is therefore an affront to the sovereignty of the individual…

…To date, the most politically successful response to the fiscal dilemma Bell identified has been proffered by anti-tax conservatives. In response to the 1978 success of Proposition 13 in California, this anti-tax movement launched a decades-long “permanent tax revolt,” that seeks to cut taxes at all levels of government. As Grover Norquist, one of the movement’s key strategists, once told Mara Liasson on NPR, “I don’t want to abolish government. I simply want to reduce it to the size where I can drag it into the bathroom and drown it in the bathtub.” The consequences of the tax revolt are now being felt across the nation as state governments make deeper cuts in spending for education, health care, and basic social services on which significant sectors of the population depend.

While riding the tax-revolt tiger has been a great political strategy for the Right, it leaves their political leaders with no effective means of governing postindustrial societies. Former President George W. Bush tried the approach of cutting taxes and increasing public sector spending, but the economy blew up on his watch and his own political popularity cratered. Yet the recent experience of the Conservative Government in England shows that the opposite tactic — cutting both taxes and spending– tends to produce a weak economy and high voter dissatisfaction. Moreover, as we have seen in the United States since 2008, both large deficits and slow growth work to push conservative voters further to the right as they embrace ever more radical schemes for slashing state spending. The intensification of the Right’s anti-government ideology constitutes the deep threat to a liberal society about which Bell warned because of its potential to engender years of destructive political stalemate.

Of interest, Block critiques several of the dominant approaches to the challenge of small government conservatism from liberal thinkers, focusing particularly on efforts to re-frame the role of government and to re-vitalize public ethos through efforts at building up networks of social and civic capital.

The Center-left largely ignored Bell’s warnings until a long series of electoral defeats in the 1980s forced them to search for solutions. We can identify three distinct strands of response, each with a mixed and uneven history. The first are reframing efforts designed to persuade the electorate that the public sector is worthy of support. For example, former President Bill Clinton campaigned in 1992 by emphasizing the need for “public investment” to get the economy going again, and President Obama used similar rhetoric in the 2008 election. While the framing was helpful in both elections, neither president persuaded the public that an expansion of government efforts was necessary. Both times, Republicans were able to use familiar anti-tax and anti-spending rhetoric to make dramatic gains in the very next election cycle.

Outside of the framework of presidential campaigns, efforts to change the discourse have been similarly ineffective. A number of progressive think tanks and consultants have tried to find fresh ways to make the public sector sound better to the public, but such efforts have not deterred conservative politicians from demonizing schoolteachers, firefighters, and police.

The inadequacy of reframing is especially evident in California. Over the last 20 years, the state’s electorate has become reliably Democratic. With higher rates of union density than most other states and growing voting blocs of Latinos and Asian Americans, the state has produced a series of strongly liberal political figures. But despite a real shift in the state’s political debate, the same electorate that routinely returns Democrats to all statewide offices still votes down most ballot measures that threaten to increase taxation. While the permanent tax revolt no longer leads to the election of Republicans, it still has enough power to block tax increases and thereby force the state to enact draconian budget cuts.

Instead of re-framing the role of government or creating new mediating institutions for the public, Block concludes that we are still in search of what Bell called for as a new public philosophy.

Thirty-five years ago, Bell correctly identified the issue that has become the pivot of our politics ever since and, as Bell suggested, solving the problem requires nothing short of a fundamental paradigm shift in how we think about society. This paradigm shift requires two steps. First, we need to move beyond the 19th century idea that society is a unitary entity that necessarily revolves around the organization of the economy. As Bell realized, it is vital that we transcend market liberalism with its insistence that we live in a market economy and have no choice but to obey its commands. Unfortunately, in the years following the publication of Cultural Contradictions, those market liberal views have become ever more dominant, surviving even the 2007-2009 financial meltdown that they were instrumental in creating.

Bell’s view is that we live simultaneously in a polity, in a culture, and in an economy, and each of them makes different and conflicting demands on us. But preserving a liberal society requires that no single one of these realms be dominant. Dominance by politics gives us the totalitarian regimes of the mid-20th century. Dominance by the economy looks like Dickensian England with its dark satanic mills. And dominance by culture produces theocratic regimes with virtually no personal freedom.

But this is only the first step. The second and even more difficult step is to articulate a political philosophy that tells us how we can give each of these realms their due without allowing one of them to dominate over the others. Bell urged us to take up this task over three decades ago. We have already paid an enormous price for ignoring his counsel. As he predicted, the survival of a recognizably liberal society could depend on our ability to rise to the challenge.