How Rodin Brought Sexy Back to Sculpture

“Art,” Auguste Rodin once said, “is only a kind of love. I know quite well that bashful moralists will stop up their ears. But what! I express in a loud voice what all artists think. Desire! Desire! what a formidable stimulant!” Love was the drug that art, particularly sculpture, was waiting for, and Rodin positioned himself as the main dealer of that “formidable stimulant.” In David J. Getsy’s Rodin: Sex and the Making of Modern Sculpture, Rodin emerges not only as a sculptor of sexually charged works, but also as a sculptor who made sex integral to the very practice of sculpture. After centuries of art that looked back to classical days, Rodin brought sexy back to sculpture and ushered in a new age of modern sculpture emphasizing the individual, including the individual expression of desire.

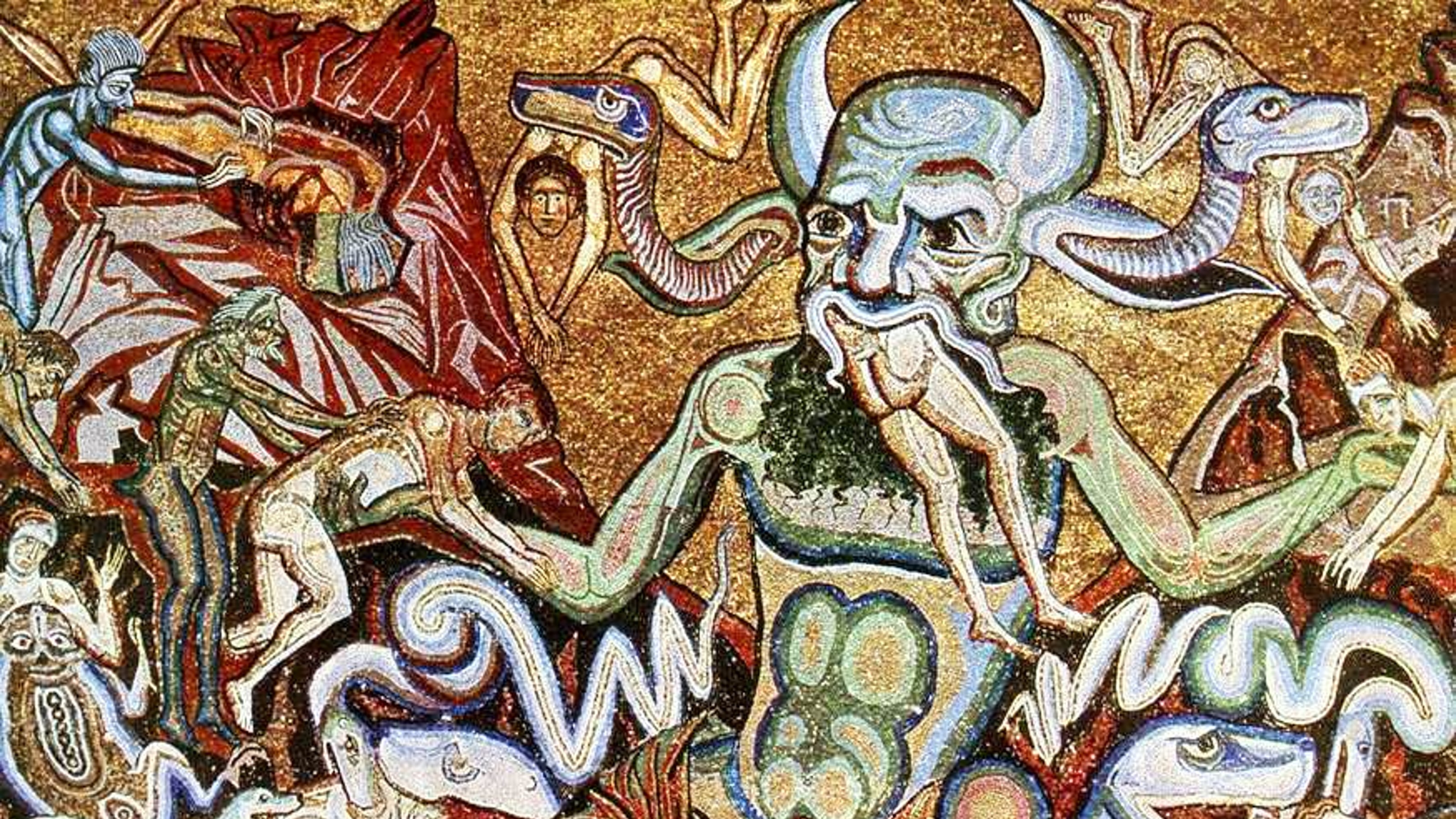

Getsy, the Goldabelle McComb Finn Distinguished Chair in Art History at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, manages to take what seems to be the most obvious aspect of Rodin—his sexuality—and look at it in a fresh and compelling way. Rather than repeat the familiar approach of analyzing the sexual content of works such as Rodin’s Eternal Springtime (shown above), Getsy approaches Rodin by analyzing the process in which he arrived at that content. He organizes that analysis by focusing on two pivotal moments in the making of Rodin the sculptor: 1876, when Rodin traveled to Florence to study his idol, Michelangelo; and 1900, when Rodin presented a one-man show just outside the entrance to the Exposition Universelle that featured his vision of the entrance to the underworld—his unfinished Gates of Hell.

“Michelangelo revealed me to myself,” Rodin recalled years later of that first face-to-face meeting in Florence in 1876. One work by Michelangelo that helped Rodin find himself was the Tomb of Giuliano de’Medici, which Rodin drew again and again. Accompanied by a generous selection of Rodin’s drawings (deftly selected by Getsy from archival photos rather than the originals unfortunately damaged by conservators), Getsy shows how these drawings by Rodin are “a conflicted interrogation of Michelangelo’s character…, rather than his style.” Looking closely at Michelangelo’s sculpted bodies, Rodin copied not their external realities but their spiritual interiors, including the warm sensuality beneath the cool marble. “Under the guise of faithful mimesis,” Getsy writes, “Rodin transformed these bodies into his own.” 1875 marked the 400th anniversary of Michelangelo’s birth and questions of his sexual orientation already swirled about the artist. Rodin took Michelangelo’s homoeroticism and translated it into his own heterosexual language. What Rodin copied most from Michelangelo, even when unfaithfully copying his content, was being true to oneself, which Getsy calls the “imperative to find a means to visualize and convey [your] own persona in the work of art.”

Rodin chose the persona of the sexual sculptor of sexual subjects. Whereas earlier sculptors gained fame through the finished results, Rodin rose to prominence through his practice. Legends of Rodin sleeping with his models lent a new dimension to his “hands on” approach to the depiction of the human figure. “Rodin refashioned nineteenth-century sculptural techniques in such a way that his works called attention to themselves as material things purposively made by him,” Getsy argues. Sexual creativity—generating life through the sexual act—became for Rodin the key metaphor for the artistic creativity—generating artworks through the sculptural act. The signs of Rodin’s touch (fingerprints and other marks) visible on his sculptures personalized his artwork more powerfully than any signature. “[U]ltimately,” Getsy asserts, “Rodin’s acts of making were mythologized as acts of love, lust, passion, and desire, visible in and as the sculptor’s touch.” (Getsy also analyzes how these marks, reproduced from the clay originals onto bronze and marble copies, began as signs of authenticity but ended for many as false affectations.)

The Gates of Hell stood as the ultimate symbol of Rodin as a procreative sculptor. Rodin presented the work to the public in an unfinished state in 1900, and never arrived at a final arrangement even at his death. Throughout the life of the work, Rodin never stopped adding, subtracting, recombining, and repositioning the smaller figures that comprised the protean whole. Paradoxically, here was static sculpture that moved. “Inverting the priorities of relief sculptural representation,” Getsy believes, “Rodin’s surface [of The Gates of Hell] becomes an active participant rather than a passive backdrop.” With that reprioritizing of the creative act over the creation itself, Rodin set the stage for every modern art movement that followed. Rodin “bridg[ed] the alienation of conception from execution,” Getsy concludes, giving birth to modernity’s marriage of those two aspects of art from Picasso onwards.

Opinions of Rodin’s sexy sculptures range from sweetly romantic to salaciously graphic. David J. Getsy’s Rodin: Sex and the Making of Modern Sculpture rehabilitates that sexual component in Rodin by making it human. Just as sex is a natural and healthy part of human life, sex is a natural and healthy part of human art—the engine driving all creation. There’s a rumor that the figure in Rodin’s Monument to Balzac is holding his own penis under that enveloping cloak. Some may see that act as a crude joke. Getsy argues that it marks instead one creative artist presenting (albeit in secret) another creative artist unashamedly clinging to the source of creative power. After reading David J. Getsy’s Rodin: Sex and the Making of Modern Sculpture, you will never look at or think about Rodin’s sexy subject matter the same way again.

[Image: Auguste Rodin. Eternal Springtime. 1894.]

[Many thanks to Yale University Press for providing me with a review copy of David J. Getsy’s Rodin: Sex and the Making of Modern Sculpture.]