In Congo, “A Dead Rat Is Worth More Than the Body of a Woman”

Sexual violence against women occurs everywhere in the world, yet a strife-torn pocket of the Democratic Republic of Congo has recently become a global focal point for such attacks as incidents of rape, violence and brutality have skyrocketed.

The scale of sexual violence in the Congo right now is the worst in the world. There were more than 15,000 rapes recorded in the Congo in the past year, according to the head of the U.N. peacekeeping mission there. In a four-day period at the end of July alone, 303 civilians were reportedly raped in 13 villages along the eastern border. In the province of South Kivu local health centers report that an average of 40 women are raped daily, according to the U.N.’s 2010 State of World Population Report.

Much of the violence has occurred in and around mining communities, where rebel groups and government troops clash for control of lucrative gold and coltan deposits.

Eve Ensler, author of “The Vagina Monologues” and founder of the advocacy group V-Day, recently toured the region, speaking with women about the attacks. She told Big Think that rape and brutality have become tools of war that are now used to destroy and scatter communities from around these mines. The brutality is an “incredibly inexpensive tool for controlling and eviscerating the population,” she says. The result, says Ensler, is a systematic pogrom against women to destroy the Congolese communities so that rebel groups and outsiders from Rwanda, Burundi and Uganda can take over the mines.

“I think the Congo has always been a place where women have been severely repressed, where they have not had access or a realization of their rights,” says Ensler. “This desecration on top of this has further impeded women’s confidence.”

What becomes apparent about Congo, as well as about such attacks everywhere, is that the sexual violence isn’t about sex, but rather is about power. “Sexual violence is there for one thing and one thing alone, which is to keep patriarchy in place,” says Ensler. Without such violence, she says, “there would be no threat to women, no way of controlling women, and no way of undermining women.”

Ensler also points out that while each act of violence has unique qualities, there are similar undercurrents common to all brutality against women. “The variation of the violence changes from place to place,” she says, “but the mechanism and the reason for it is the same.”

The U.N. has attempted to gain ground in the region and stop the violence, but its gains have been slow. Margot Wallström, the U.N.’s Special Representative on Sexual Violence and Conflict, visited the Congo in October and came away with the conclusion that such rampant sexual violence “brutalizes the whole society.” Rape destroys communities by stigmatizing the victim, she says, and then becomes a legacy issue as the following generation of young men and boys come to believe that such acts are natural.

As the destruction ripples from each individual through the whole society, it starves opportunity at each stage. Women are, in many ways, the backbone of the Congolese economy and society, says Wallström. Since the violence began, the economic and social structures framed by women, from familial roles to labor, have been fractured. In the fight to control resources and their wealth, the violence has hobbled economic development in the country.

Opportunity fails as well on the individual level. Drawing from work by the U.N. and from stories heard during her visit, Wallström compares the ongoing sexual violence to killing a person without taking their life. Often, she says, when a woman has been raped she is rejected by her husband and family and she is marginalized and stigmatized without income or resource.

“A dead rat is worth more than the body of a woman,” one victim told Wallström.

During her visit, Wallström asked a Congolese woman what “normal” would be if she had not been brutalized. “She didn’t seem to understand the question,” Wallström says. “She said that the life of the woman is to work. … to give birth to children and then to sort of please your husband and do whatever he tells you sexually at night. That’s the life of a woman. And there was sort of no joy, no love, no concept of what we would think was a dignified life.”

Even amid such unconscionable violence, Ensler believes the future of Congo is found in its women. Through her organization’s work she sees “more women coming into their power, more women coming into their voice, more women believing they have a right to be.” If current gains are sustained and many new gains made, Ensler says, “the women in Congo in the next five years will indeed rise up, and will indeed take over, and will indeed come into a voice of power.”

More Resources

—Eve Ensler’s V-Day Congo Campaign

—U.N. State of the World Population 2010: From Conflict and Crisis to Renewal: Generations of Change.

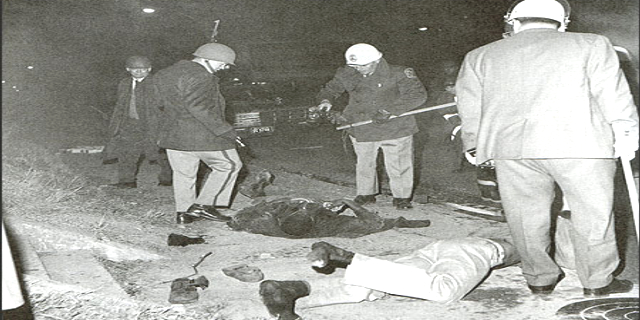

*Photographs by Myriam Asmani/MONUSCO