Is the Pope’s Statue a Sin Against Public Art?

Everybody’s a critic, especially when it comes to public art. Mix in religion, a beloved figure, and modern art and you’ve got yourself all the ingredients for controversy. The recently unveiled statue of Pope John Paul II by Oliviero Rainaldi may be the most hated piece of art on earth at the moment. The Vatican beatified the beloved Polish pontiff earlier this month. Rainaldi’s statue was to be a tribute in honor of that step toward sainthood from the Fondazione Silvana Paolini Angelucci, a charitable organization that donated the statue to Rome. Now, Romans want to give it back, calling it a public eyesore and a black mark against the memory of the holy man they feel it fails to resemble. In that holiest of cities for Catholics, is the statue of John Paul II a sin against public art?

Opinions, of course, are like bellybuttons—everyone has one, unless you’re an alien. Human nature compels us to be critical, especially when it comes to shared experiences. Public art continues to be the one shared art experience for societies, even for a society such as Italy’s surrounded by centuries of public art since the Renaissance. Rainaldi, a well-regarded sculptor who has gained a reputation for designing sculpture-prizes related to peace, human rights, and the family, probably seemed a good choice at the time the foundation made the pick. Perhaps he’ll prove the correct pick over time, but right now he’s anything but a favorite son.

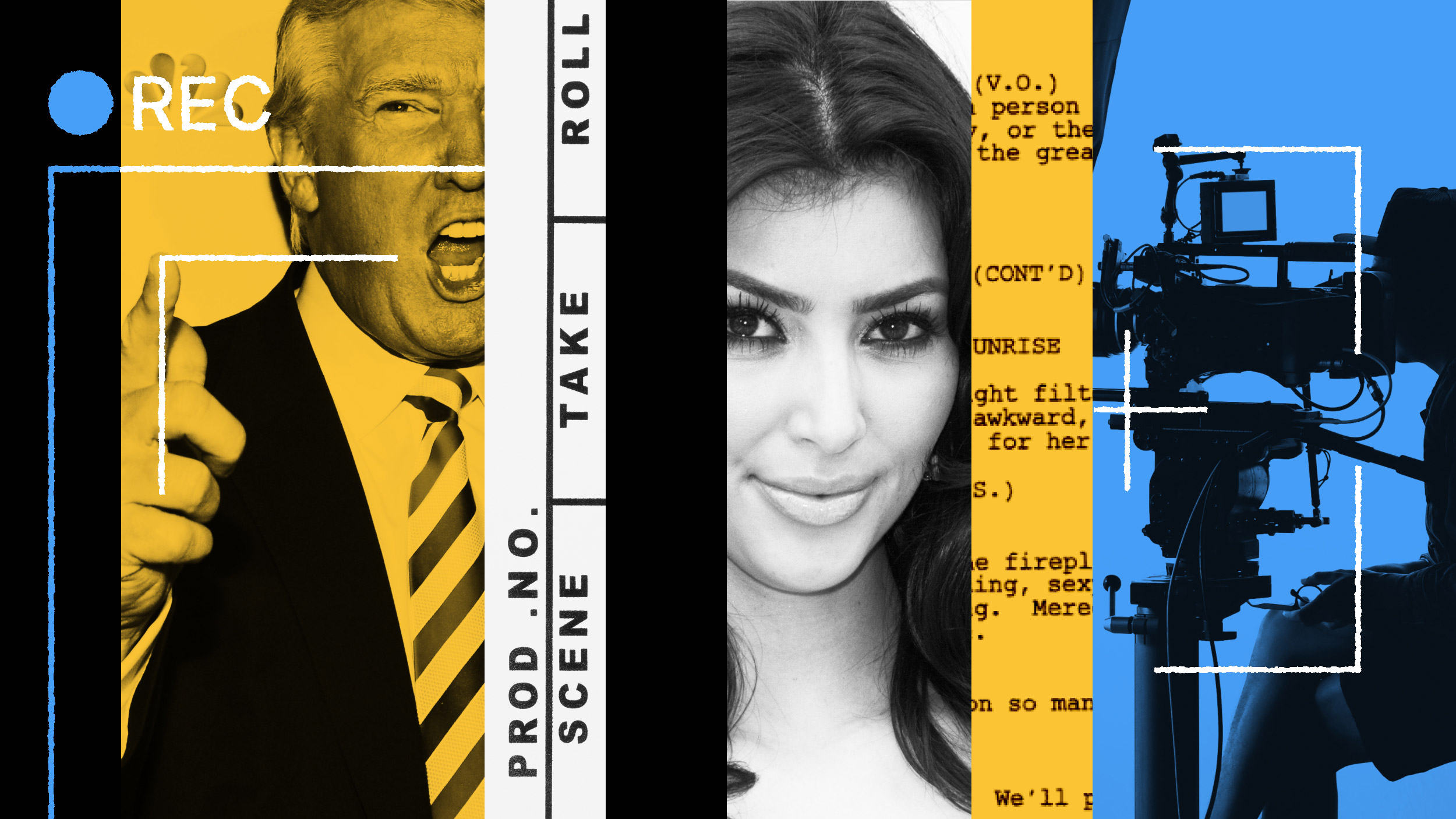

It’s hard to exaggerate how much this statue is reviled by Romans. In an online poll conducted by Il Messaggero, one of Rome’s daily newspapers, 90 percent said they hated it. Even the Vatican has come out against it. The open cloak that Rainaldi claims symbolizes the pope’s open embrace of his flock on earth makes the statue (shown above) look too much “like a sentry box,” according to the Vatican critic. The Vatican critic calls the head itself “too roundish,” which is kind in comparison to others who see more of a resemblance to Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini than to the man formerly known as Karol Józef Wojtyła. Even rougher amateur critics predict that the statue will become a makeshift homeless shelter, a collection area for beer bottles, and worse.

Rainaldi hoped to capture the essence of John Paul II. For him, the gesture of an extended hand accentuated by an open cape symbolized the inclusiveness of the late Pope’s life and legacy. Sadly, not everyone sees it that way. As much as Rainaldi tries to explain his intent, the “proof” in front of the public’s eyes proves much more powerful. Other abstract statues of the pope exist, but not in public areas, or else they might feel the same wrath. Whether the statue looks more like il Papa or il Dulce is a matter of interpretation. Perhaps those who see the dictator simply hate feeling that an artist is dictating to them how they should think about the Pope. But artists need to feel they can express their ideas without the public looking over their shoulder in what amounts to real time. Even Rodin’s Monument to Balzac, a similarly eccentric essence-based depiction, earned public disdain during its conception and execution before finding admirers decades later. For Rainaldi’s sake, and the sake of the memory of the Pope, I hope a similar salvation awaits.

[Image:Oliviero Rainaldi. Statue of Pope John Paul II. Rome, Italy.]