Moving Forward: New Wave Museum Marketing

“It’s time we Met,” reads several posters in the latest marketing campaign of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. A recent piece by Peter Aspden titled “Met on the Move” in the Financial Times queried the Met’s director Thomas P. Campbell (shown) as to what new directions the museum will be taking in bringing the museum to the public for the ever-shrinking entertainment dollar in our still-shrinking economy. As the Met goes, so goes most American museums, so listening to this canary in the coal mine can give us an early indication of just what kind of siren song museums hope to sing to lure patrons through their doors.

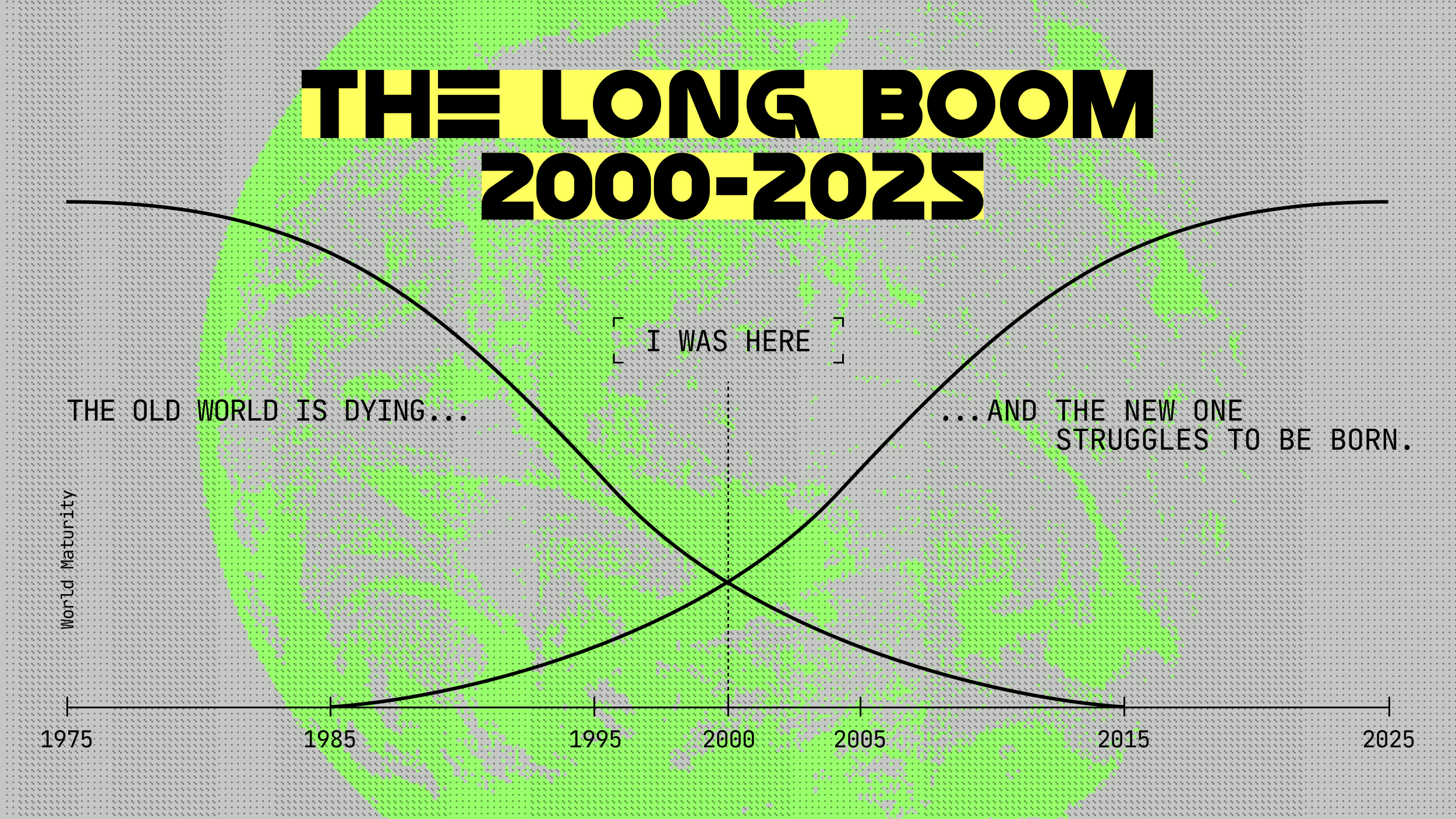

“It’s a happy scene, with a subtext,” Aspden writes of the new marketing pitch, “the austere museum known throughout the world for its academic rigour and its peerless collections is these days not above slumming it in the marketing jungle with a larky pun or two.” I hate the idea of enlivening museums as seen as “slumming.” To call it slumming is to presume that the audience for museums is purely well-educated, well-off people and their families. Museums need to widen their audience for the practical reason of survival. More importantly, and less often argued, is the need to foster intellectual curiosity in the public, especially in the young. The picture of three children in the Egyptian section of the museum grinning before a fourth friend “mummified” in toilet paper makes me smile not just for their hijinks, but also because those kids most likely lingered in that section. Lingering in just one section probably led to discovering another and another. The average age of most audiences for cultural events in the United States is extremely high. This audience is literally dying out. For cultural outlets to survive, they need to cultivate the young. Get ‘em young, and you’ll get ‘em forever.

“We assume people know who Rembrandt is, for example,” Campbell says in the piece. “We have wonderful, thoughtful labels next to each Rembrandt painting, but there’s no overview of who he was and, frankly, considering our international audience, I doubt whether many of them do know who [he] was, or the significance of a particular period room, in a broader context.” True learning is always done in context. Unrelated facts flow in one ear and out the other, clinging to nothing in between. String those facts together into a narrative—a story full of context—and people will connect, learn, and want to learn more. It’s simply the way that memory and the mind works. American education has too long resembled a fact factory pumping kids full of disconnected data and deciding that regurgitation of that data on standardized tests represents some kind of learning. If museums are going to educate the next generation of gallery goers, they need to listen to Campbell and follow the Met’s example of becoming educators not through more new technology or more wall plates but through good old fashioned storytelling. Art survives and makes us think because it is always relevant to us today. The old stories are forever new in their retelling and their assimilation into new minds. Moving forward for museums will begin with two steps back into the past before taking that one great leap into the future.