Orangeburg Massacre A Part Of The American Mosaic

One of the bad things about having a smart phone is, I can now scroll through the headlines of the New York Times before I get out of bed. This morning, I was running down the list of the latest headlines when the words “Orangeburg Massacre” caught my eye, mostly because this little known tragedy that occurred in South Carolina during the late sixties took place in my hometown. The article reviewed a play created by Calhoun Cornwell, a young man from Orangeburg who was inspired by hearing the story of a civil rights protest gone horribly wrong.

As soon as I saw the words “Orangeburg Massacre”, the names Smith, Hammond and Middleton went through my mind. The Smith Hammond Middleton Memorial Center, located at the rear of South Carolina State University’s campus, was an important hub in my life. When I lived a few blocks from the gymnasium/natatorium, I used to ride my bike around its parking lot and play on its steps.

I learned to swim in the huge pool behind the building’s main arena. I saw my first concert on its stage. My high school held our junior senior prom on there, and our graduation took place there. If you are from a small town, you probably already know why so many big events took place here—it was the biggest facility in town. Locally, at least when I was growing up, it was known as “SHM”, a shortened moniker that predated today’s obsession with acronyms by a generation.

It wasn’t until I was in my early twenties that I began to understand the significance behind the names inscribed across the entrance to the building. Many of my relatives, including my father and several of my uncles and aunts, attended South Carolina State University back when it was still a college. One of my aunts was a student here the night Smith, Hammond and Middleton were shot. Family folklore had my grandfather racing up from his farm in Berkeley County to Orangeburg, where my grandmother promptly climbed into the bed of the pickup truck and acted as a sentry, her shotgun across her lap, as my grandfather drove through the town streets to retrieve my aunt.

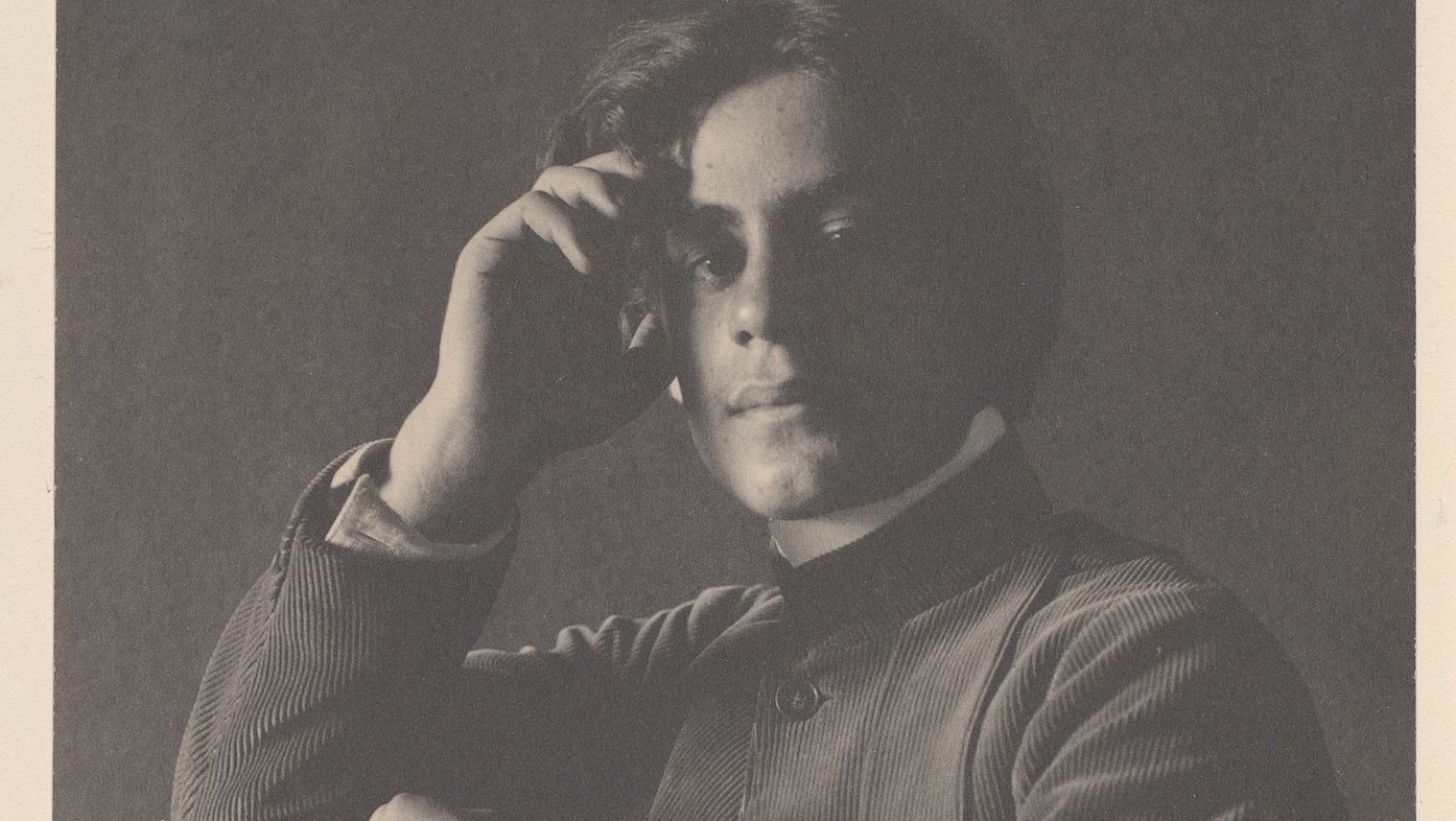

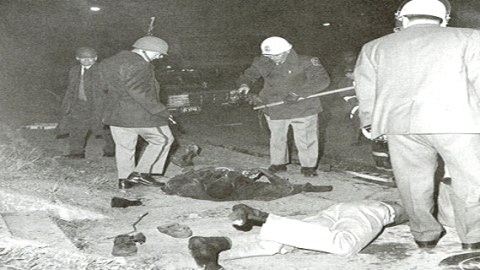

The New York Times editor went to the same public domain archives I did to select the picture of the National Guardsmen marching in Orangeburg after the shootings to help illustrate the story. I chose the photo above because in the end, this is a story about three real people who were gunned down on the streets of my hometown for daring to protest the racial inequities of the times.

Times did change—I have marched down the very same Russell Street the National Guardsmen patrolled during the tense time after the massacre as a student at Orangeburg-Wilkinson High, a school that consolidated the white Orangeburg High with the black Wilkinson High in 1970—but the American mosaic will always be incomplete until the stories like this one, and the countless others chronicling the struggle of our nation’s minorities to gain the full measure of their citizenship, are as well known to the general public as the Star Spangled Banner.