Out of Our Depth: Turner, Painting, Drowning, Swimming Pools, and Meaning

If you read as much about art as I do, things that seem unrelated on the surface tend to pool together in the eddies of my consciousness. Two unrelated concepts that recently flowed together into a confluence were Sarah Monks’ essay, “Suffer a Sea Change”: Turner, Painting, Drowning, and Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica and filmmaker Neville D’Almeida’s 1974 collaboration CC4 Nocagions (above) in MOCA’s Latin American art exhibition Suprasensorial. Monks explains how J.M.W. Turner’s sea paintings dipped into the Romanticism of the era, specifically the idea that the ocean depths symbolized the depths of the human imagination. Oiticica and D’Almeida’s artwork consists of a swimming pool ringed in neon in which patrons can swim and join in the performance. Putting those two concepts side by side, I couldn’t help but wonder if we as a culture have gotten out of our depth, specifically the ability to do something other than skim the surface of meaning.

Monks’ essay in the Autumn 2010 issue of Tate Papers “focus[es] on the ways in which J.M.W. Turner set about suggesting, to an extent which is unprecedented in the visual representation of water, what it might be to be beneath–beneath the horizon, beneath the water and beneath paint.” After the relentless rationalizing of the Enlightenment, the pendulum swing back to the emotions of Romanticism recast the world of facts as a huge mirror—a view of nature in which everything corresponded to some aspect of the human mind. Turner recognized this aspect of Romanticism and plumbed the depths of how deeply we can look into the mysteriously rolling waters of the seas and see the unknowable depths of the human mind. As Monks points out, paintings such as Fishermen at Sea and Snow Storm–Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth making Signals in Shallow Water, and going by the Lead. The Author was in this Storm on the Night the Ariel left Harwich demonstrate Turner’s use of “the sea’s redesignation in contemporary [19th century] culture as a space where, par excellence, transcendent mastery might be realised, and where the real extent of one’s physical, moral and aesthetic responsiveness might be revealed.” The sea truly existed as a port of departure for an imaginative “sea change” in which the individual could transcend the mundane.

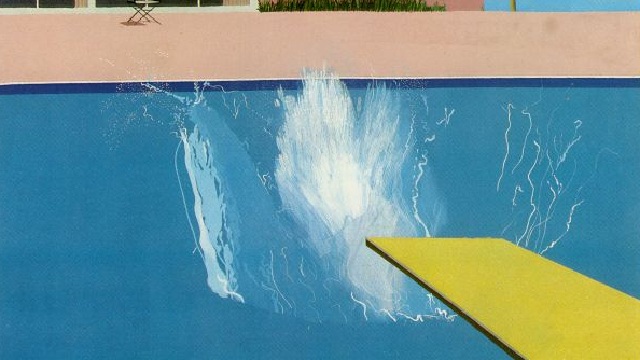

By contrast, Oiticica and D’Almeida’s swimming pool asks only that you take a dip. A lifeguard on duty supplies the towels and disposable swimming suits can be purchased in the museum shop. CC4 Nocagions belongs to a larger series called Cosmococas, with the “cocas” referring to cocaine—the narcotic bane of Latin (and North) American existence. The collaborating pair allegedly indulged in the white powder while conceiving the swimming pool idea. In the room in which the pool resides, images from minimalist composer John Cage‘s book Notations appear projected on the walls, but with white lines of cocaine traced on them by D’Almeida. Blue rope lights on the side of the pool and an eerie green light dancing upon the water complete the scene.

I hate to minimalize Oiticica and D’Almeida’s work, but juxtaposed with Turner’s paintings, it looks like a puddle beside an ocean. Perhaps what really bothers me is how each work reflects its time so perfectly. It’s always dangerous to cast any time as a golden age, but the 19th century cherished its contemporary artists in a way inconceivable today. Turner entered the gallery of annual exhibitions like a rock star takes the stage now. The merging of zeitgeist and individual artwork seems perfect in Turner’s paintings, as Monks points out. Again, this may be sentimental hindsight, but, like Monks, I truly believe that Turner actively incorporated contemporary ideas into his art and resounded in a deeply lasting way because of that.

Sadly, CC4 Nocagions may actually reflect the zeitgeist of the last few decades better than I’m willing to admit. Rather than embrace the tempestuousness of the vast sea, we as a culture prefer our nature tamed—reduced to the comfy confines of the backyard pool. The cocaine-laced presentation hints at the relentless self-medication into mindless somnolence we’ve reduced ourselves to with every drug on the spectrum from crack to Twitter. It’s tragic how disposable art has become, like a pair of cheap trunks purchased to swim a few quick laps around the cultural pool before tossing them out in the trash. I’m inclined to see Oiticica and D’Almeida not as part of the problem, but instead as merely a symptom or, even better, a diagnosis. Like Turner, they’re just giving us a mirror in which to see who we are—in this case, a mirror covered with lines of cocaine and rimmed in garish neon light.

Maybe I’m overthinking this, but maybe that’s the problem. On the whole, overthinking is a rare thing today. We’ve grown so averse to the idea of intellectual depth—that anti-democratic, elitist enterprise—that we’re completely out of our depth as a culture in too many ways. Perhaps I’m advocating a return to Romanticism (I am a Romantic at heart), because the shallowness of our art today reflects the overall shallowness of our thinking and, tragically, our feeling—the empathy that makes us human and makes the world a more reasonable and livable place. Just as it’s possible for a human to drown in an inch of water, we’re drowning today in the very shallowness we’ve surrounded ourselves with. So, please come take the plunge into the deep end of the intellectual currents of today. The water’s fine.