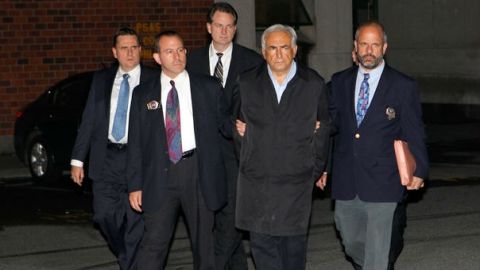

Power and The Ease of Amorality: The Illustrative Example of Dominique Strauss-Kahn

Power changes how we make decisions. That’s what I thought when I first read about Dominique Strauss-Kahn’s debacle – and the escapades that have apparently preceded it. Actually, the first thing I thought was, seriously? Did he seriously think he could keep getting away with more and more egregious behavior? And then came the answer: of course he did. It makes all of the sense in the world. And the longer he remained in power, the more powerful he was and felt, the longer he got away with first small and then increasingly larger transgressions against the fair sex (and perhaps others, too – at this point, who knows), the more likely it became that he would continue to transgress – and think himself untouchable while doing so. It’s only natural, that feeling of arrogant entitlement.

The amoral repercussions of power

Why? Consider this. A recent study (currently under review) at Columbia Business School examined what would happen if individuals were told that there was a $100 bill in a book, in a room where they would be by themselves for approximately five minutes. Each participant was instructed to either take the money or not. Then, irrespective of that initial instruction, each participant was told to convince the experimenter (who didn’t know who had been instructed to take the money and who hadn’t) that he did not in fact take the money. If participants successfully pleaded their innocence—be it real or not—they would keep the $100, and be eligible for a lottery to win $500 more.

The whole time, participants were recorded on video (unbeknownst to them). They were also asked to give saliva samples, to be tested for cortisol, a known stress hormone.

Crucially, prior to this manipulation, everyone had also been asked to play either a low or a high power role. Participants were randomly divided into managers and subordinates (though they believed that they had been divided based on the results of a “Leadership Questionnaire”), and took part in a role-playing simulation that has been shown in prior studies to effectively manipulate feelings of power.

So what happened? Power didn’t suddenly make people amoral. That is, they still stated that they believed lying was wrong. However, only one group actually experienced emotional distress after lying: the low-power liars (the subordinates who took the money but had to convince the experimenter they hadn’t). The high-power liars didn’t report any negative feelings. Moreover, whereas low-power liars were cognitively impaired after the deception, high-power liars weren’t. Most tellingly, whereas low-power liars had the cortisol spikes that one would expect with stress, high-power liars had a hormonal signature that was identical to that of the truth-tellers. And the difference was physically apparent: low-power liars showed signs of nonverbal distress when convincing the experimenter that they were telling the truth, but high-power liars did not.

Power protects against the stress of moral contradiction

These findings point to one possible thing that may be happening when high-power individuals go, so to speak, astray: as people gain power, they are emotionally and physiologically buffered against the stress of such morally contradictory behaviors as lying. Now, this doesn’t mean that power will make them lie or otherwise behave amorally. But it does mean that if they had the propensity to do so in the first place, it will make it easier, and will exert less of a toll on their psyches and their bodies.

Of course, power doesn’t affect everyone in the same way, and I’m not trying to claim that it will suddenly make you a bad person. No. What I’m saying is that power can exacerbate latent tendencies when those tendencies already exist – and furthermore, that people who seek power may also have some of those characteristics that would do well to remain unamplified, a selection effect, if you will.

The literature on power is vast, and obviously, this is just the tip of the iceberg. But, it should make us less surprised, less shocked in a how-could-this-happen or how-could-anyone-be-so-fill-in-the-blank way every time an Eliot Spitzer, or a Bernie Madoff, or now, a Dominique Strauss-Kahn is caught red-handed.