“Smart Cities” Are Smart Investments, Too

In his 2011 State of the Union address, President Obama sang the praises of green technology, calling it “an investment that will strengthen our security, protect our planet, and create countless new jobs for our people.” The security and environmental benefits may be clear, but most green tech companies still struggle to turn a profit. Does the economic argument hold up?

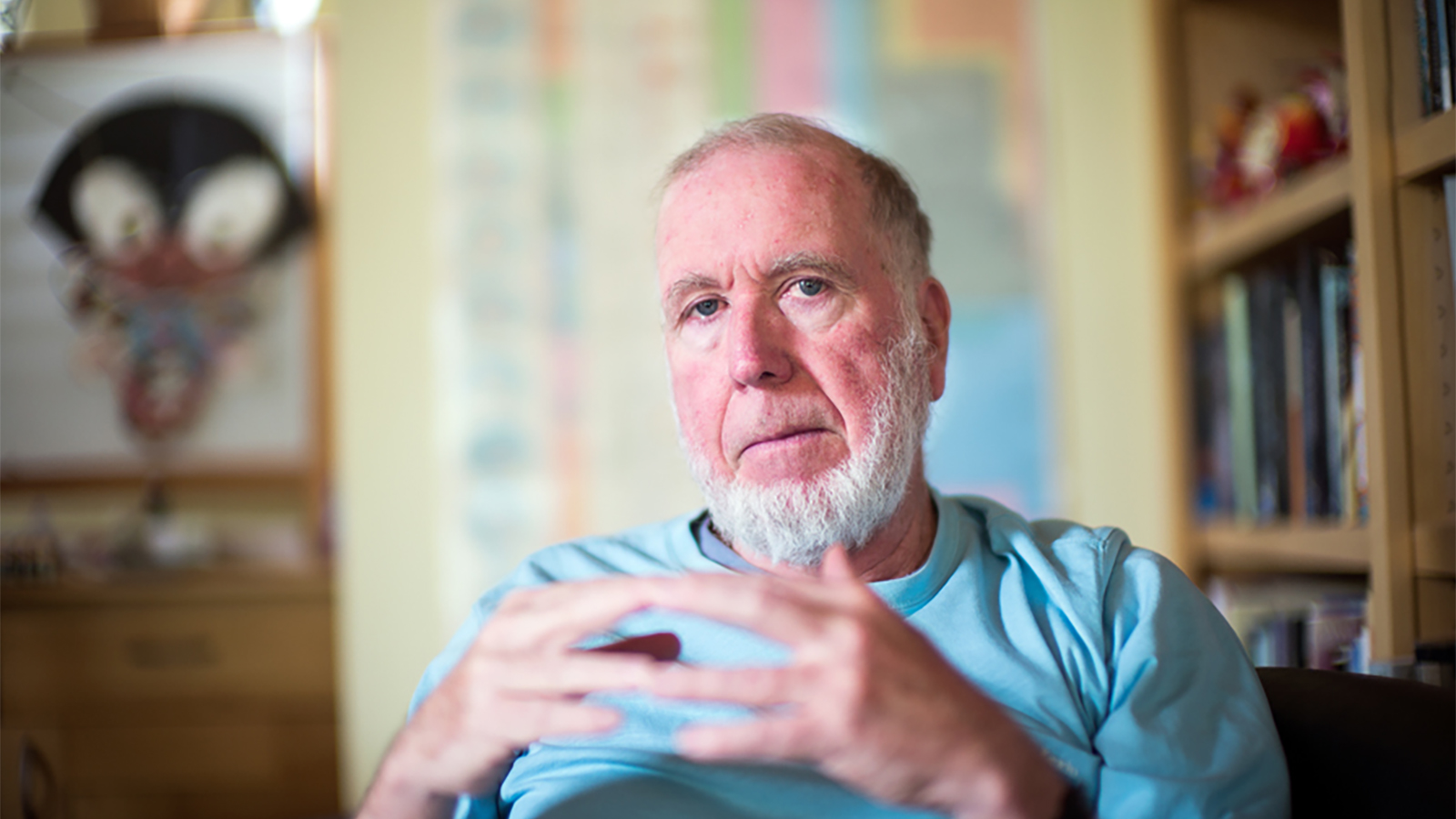

When it comes to greening our cities in particular, Harvard Business School professor Robert Eccles believes the answer is yes. In the century ahead, he says, urban sustainability will become more than just a practical necessity: it will become a “big market opportunity.” On the other hand, that opportunity may be wasted unless developers discard traditional real estate industry models in favor of a Silicon Valley-style approach.

Eccles touts a company called Living PlanIT as one of the emerging leaders of the sustainable urbanization field. Living PlanIT’s mission is to create new, eco-friendly urban centers with economies “based on research and innovation.” They’ve started with a pilot community called PlanIT Valley in Paredes, Portugal, and are hoping to expand worldwide. Eccles believes their model is “strong and viable” enough to do so. Moreover, since not all cities can be built (or rebuilt) from scratch, Eccles thinks “the so-called urban retrofit market could be an even bigger opportunity,” as existing cities incorporate new green technology into their current infrastructure.

Eccles concedes that these innovations have been unprofitable to date, but believes retrograde business thinking is to blame. “People say…none of these smart cities, green cities, have been successful, and I think that’s largely true. And that’s true because the business model that has been used is real estate development: try and get the land cheap, have deep pockets, you know…lease it, sell it.” A breakthrough may be at hand, he says, as new-generation developers apply a software industry model to the problem, focusing less on land and property units than on the underlying technological “nervous system” by which cities function.

In the past year Big Think also spoke with the late Bill Mitchell, director of the Smart Cities group at the MIT Media Lab, who agreed that the transformative technologies of our urban future aren’t likely to reshape the skyline. Instead, they’ll be more “unobtrusive,” discreetly changing the way you work, communicate, and travel—until suddenly you find yourself talking on an entirely new kind of phone, or driving an “electric toothbrush.” (And of course, some of the ideas that produce “smart” cities won’t be particularly futuristic—just smart. Witness the bike-sharing programs recently detailed by Big Think blogger Maria Popova.)

While green tech has yet to take our cities by storm, it’s clear that cutting-edge entrepreneurs are beginning to take serious gambles in this arena. If they pay off, urban sustainability crusaders will soon be able to look beyond presidential speeches for signs of hope.