Speculating on the 2011 Nabro eruption in Eritrea

The eruption of Nabro in Eritrea has been a bit of an enigma, mostly because the volcano is (a) so remote and (b) it’s previous activity is mostly unknown. In fact, when the eruption was first identified by the Toulouse VAAC, it was mistakenly attributed to the nearby volcano Dubbi, mostly because Dubbi has had an historical eruption in 1861 while Nabro, well, it is not known when the caldera system had it’s most recent eruption (likely in the last 11,0000 years is the best guess). This makes interpreting the current activity, and more importantly how the eruption will proceed, very difficult. We have been fortunate that the volcano has, for the most part, been visible on satellite images of the area just south of the Red Sea, so the light grey/tan plume was captured speeding across northern Africa. Beyond this, though, we didn’t have a lot of information from the ground to understand what sort of eruption was occurring at Nabro.

Luckily, we’ve been now getting more information about the true nature of the eruption. The NASA Earth Observatory posted a new image that was able to capture a glimpse of a lava flow (see below) from Nabro, one that has travelled 15 km since the eruption (of note, that is a guess as to when the lava flow began, as it could have started days after the initial explosive component of the eruption). There has been a lot of speculating about what the composition of the lava flow might be – and you might ask how can the composition of a lava flow be determined by just looking at a satellite image. Two main factors can betray what type of lava is erupting: viscosity and temperature. Viscosity will determine how quickly the flow moves (for the most part) and what sort of morphology the flow might have – well-developed levees, a steep snout to the flow, prominent pressure ridges. You can usually tell the difference between a basaltic lava flow (low viscosity) and a rhyolite lava flow (high viscosity) by looking at these features – a basaltic lava flow will likely not have a steep snout (it might have piles of rubble at the snout, though) or sides but instead stay channelized until it reaches flat ground, when it spreads out into flat lobes. In terms of temperature, basaltic lava is much hotter than rhyolite or even andesite lava, so it should appear to be quite hot in any thermal image of the volcano (but how hot exactly is trickier and requires some guesses about the composition before we know the composition). Looking at the NASA EO image (below), a good guess would be that the lava flow is basaltic in nature because it traveled a long distance in a short time (implying low viscosity), it doesn’t appear to be particularly thick and it spreads out significantly in the lowlands.

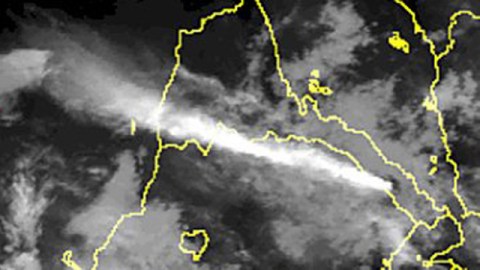

There is now footage of the eruption itself taken from the ground – or a least images of the lava flow (see below) – that supports the conjecture that the lava flow is basaltic. You can see the black-and-red advancing basaltic lava flow (looks like a`a) that is the very end of the lava flow. So, it appears that the Nabro eruption is not only producing an ash plume but also an impressive lava flow which, when looking at the NASA EO image or the DEM (below), shouldn’t be a surprise with the older lava flows and cinder cones present (and note that the current eruption is close to the older cinder cone on the west side of the Nabro caldera).

Image of the Nabro lava flow (or at least believed to be from the Nabro eruption).

Now, why the eruption started off so explosively is entirely speculation at this point. As we’ve seen before, there are a lot of reasons why an eruption might be explosive: interaction with surface water/ice, interaction with a high silicic magma or mush in the volcano, high initial water content in the magma. At this point, we don’t have any evidence to say which might be the case here, although the location would mostly eliminate surface water/ice interaction. The Nabro volcano is a caldera that has seen explosive eruptions in the past, so this new intrusion could have interacted with pre-existing mush under the volcano or this new basaltic intrusion might have just had a lot of water dissolved in the magma. Further investigation of the initial ash will likely solve this problem.

This eruption at Nabro has left a lot of people scratching their heads, but explosive eruptions and large lava flows at calderas aren’t uncommon. Iceland is a good example where you get caldera formation and basaltic lava flows from the same system. Another example might be Newberry Caldera in Oregon (see below), where you have big rhyolite flows and a caldera all mixed with abundant basaltic lava flows. All of this type of activity tends to be related to a rifting environment – where the crust is thinning. In these setting you can develop bimodal volcanism where both basalt and rhyolite erupt. The rhyolite is usually generated by either remelting the pre-existing crust or crystallization of the basalt (to produce a rhyolite liquid). When the basalt intrudes in places where it has a fairly unimpeded path to the surface, basaltic eruptions occur (usually on the flanks of the caldera). Nabro is in a similar extensional setting as Newberry (or California’s Medicine Lake) – be sure to check out the new post on Highly Allochthonous about the structural implications of the Nabro eruption – so we might expect to see some similarities.

High altitude image of Newberry Caldera, showing the Paulina and East Lakes in the caldera and the apron of pyroclastic deposits and basaltic lava flows surrounding the caldera.

Now, a lot of what I’ve said here is speculation – we just don’t have a lot of information on Nabro and the eruption itself to make any concrete conclusions. There isn’t much record of volcanism in Eritrea, so this new data point will hopefully add significantly to our understanding of magma generation under the East African Rift. Thankfully, this eruption did occur in a relatively unpopulated area (although at least 7 people have been killed due to the eruption), so we can observe this caldera volcanism without the “apocalyptical” fears that usually come with it.

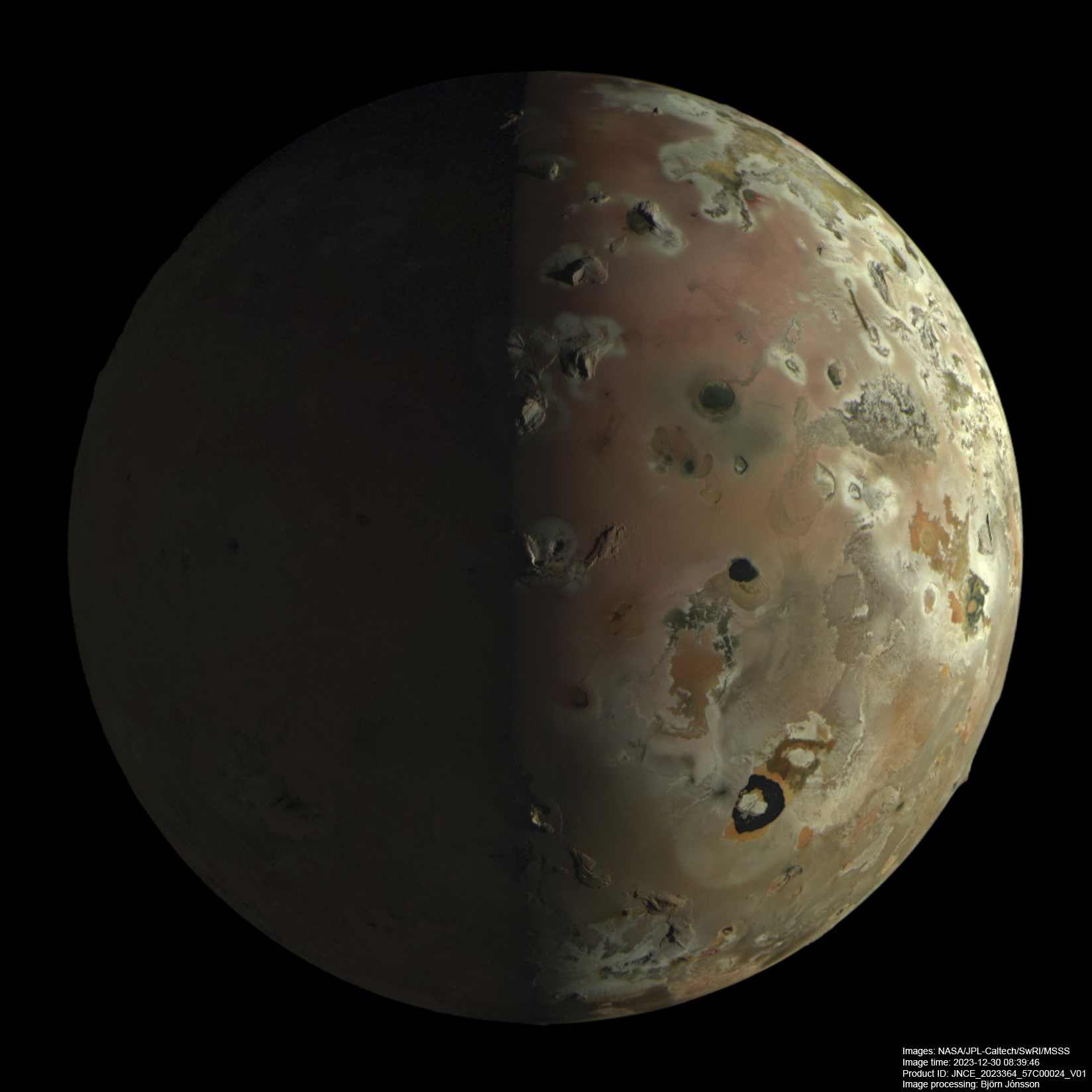

Top left: Weather satellite image of the 2011 Nabro eruption.