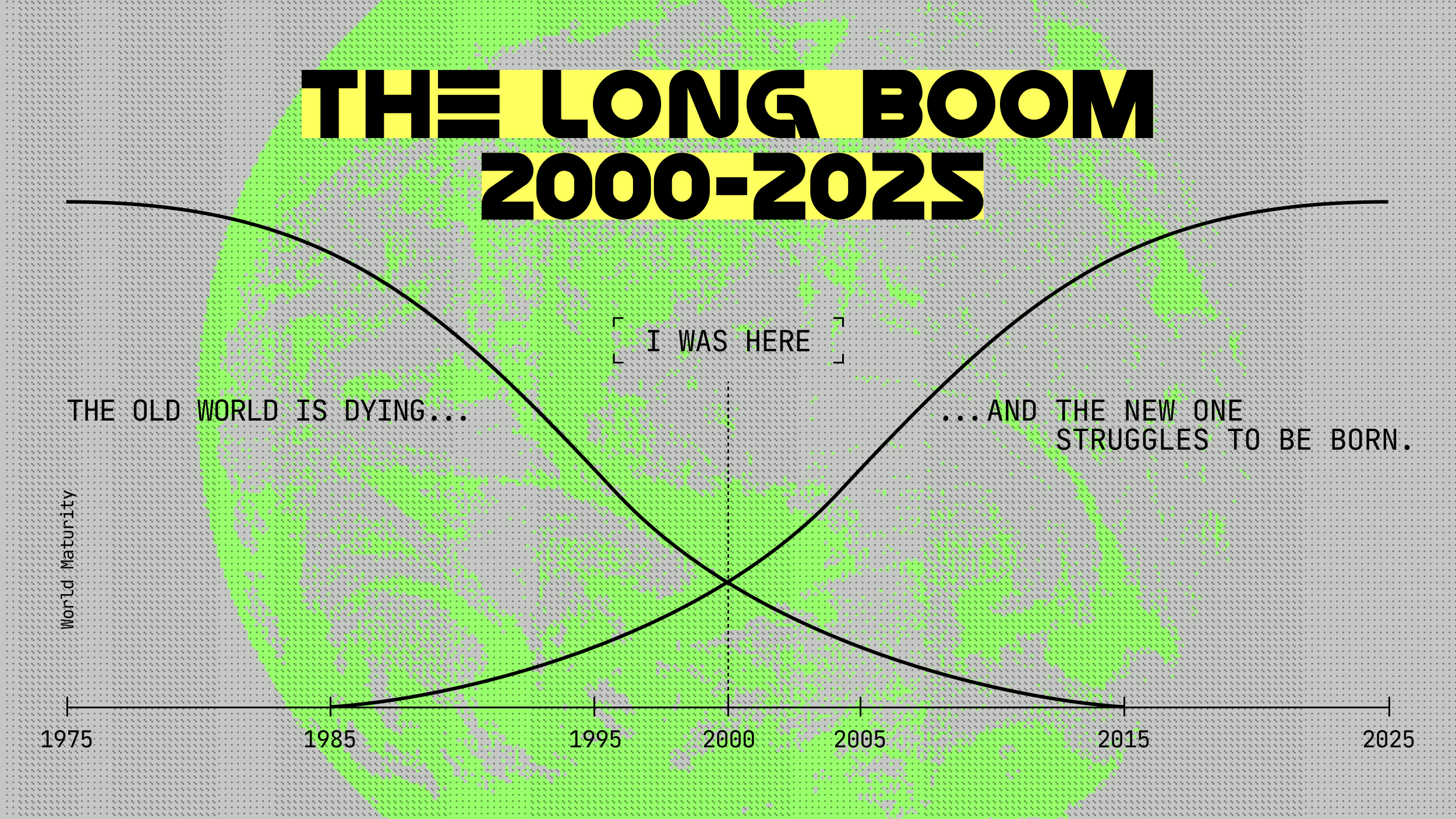

“The Literature of Humbling,” and America as Icarus

George Packer’s review of Peter Beinart’s book, The Icarus Syndrome: A History of American Hubris, is itself an elegant analysis of American history. Packer highlights some of choices our leaders have made, and exposes some ideals easier for a journalist to propose than for a President to uphold. Like the best critics, he pulls no punches. When he points out that Beinart’s book “belongs to the literature of humbling,” he is not describing a nation’s humility, but an author’s.

Beinart’s views have changed, and Packer reminds us of their arc (he calls the voice of Beinart’s earlier book “callow and insistent.”). Beinart supported the last Iraq War, but in this book he describes how his ideas have evolved, an evolutionary journey in which he was not alone (‘“The Icarus Syndrome” finds the ground littered with Peter Beinarts, lying amid the remnants of large ideas and unearned confidence,’ Packer writes.).

The review is a thoughtful chapter itself in a larger conversation, one where journalists and pundits meet scholars, politicians, policy makers and generals, one hard to parse from the outside. Not unlike other academic subcultures, this one has rules and hierarchies often unknown to casual readers. But whatever the history—or lack thereof—between these two writers, they both have made substantive contributions to the genre, and so stand in an interesting tradition.

Packer concludes:

[Beinart’s] conclusion calls for a “jubilant undertaker, someone like Franklin Roosevelt and Ronald Reagan, who can bury the hubris of the past while convincing Americans that they are witnessing a wedding, not a funeral.” In other words, don’t challenge “the beautiful lie” that Americans can do anything—but for now let’s keep it small. Barack Obama needs to find “symbolic balm for America’s wounded pride”: dress down Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Hugo Chávez from time to time; pull some dictatorships into global trade bodies and try to persuade others to sign human-rights declarations; “leaven patriotic criticism with patriotic affirmation.” These are the not very satisfying improvisations of a writer who has spent the past few years sifting through the wreckage of recent history for valuable glints. If they sound less like a foreign-policy doctrine than like an occupational therapist trying to buoy the spirits of a patient recovering from a terrible accident, that is surely Peter Beinart’s point.

Whether or not Beinart possesses the “facile brilliance” of which he is here accused (and whether or not you elect to read his book), there are two things to take from Packer’s piece: first, that the American policy debate still inspires the finest minds of a generation. Second, that you may romanticize the Wise Men of the past, but you should know there are writers and thinkers today who, while they lack the concentrated power or quality of access of an Acheson or a Schlesinger, still possess a similar discipline of mind, and an equally compelling vision about how the global chess board is composed. Are we too close to the sun? It is writing like Packer’s that will lure us back to Earth.