Truth in Milk Labeling

At the end of September, a federal court struck down an Ohio law forbidding companies from labeling dairy products as made from milk that is “rBGH free,” “rBST free,” or “artificial hormone free.” In its ruling, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals said that the law violated dairy processors’ First Amendment rights and was “more extensive than necessary to serve the state’s interest in preventing consumer deception.”

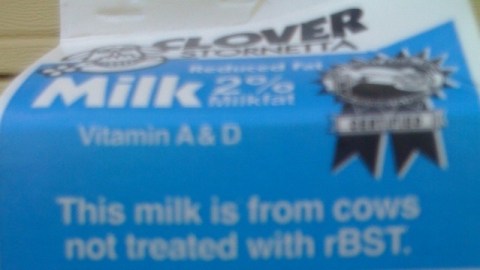

As Tom Laskway explains, rBGH and rBST stand for “recombinant bovine growth hormone” and “recombinant bovine somatotropin” respectively. They are genetically engineered versions of naturally occurring hormones that farmers inject into cows to increase milk production. The U.S. is practically the only country in the developed world to allow the use of either hormone in the production of milk for human consumption. About 40% of milk in the U.S.—along with much of our cheese and most major brands of ice cream—is still produced with the help of the hormones.

No one alleged that the dairy producers claims were untrue. Fraudulently claiming to not to use hormones would be illegal under existing law anyway. The point of the law was that saying milk is hormone free could mislead the consumer into thinking the milk itself is different from milk produced without the use of hormones. It’s true that those labels do seem to suggest that the milk itself—rather than the production process—is hormone free. But even if milk produced without the hormones is the same as milk produced without, producers should be allowed to make true statements about how the milk is made, in case those things matter to consumers. After all, use of the hormones increases the incidence of mastitis—a painful inflammation of the udders—in cows. An that means greater use of antibiotics to treat the mastitis, which may contribute to spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

The court ruled in any case that milk from cows treated with hormones isn’t the same anyway. The Ohio law was the result of a national campaign sponsored by Monsanto, which originally developed the genetically modified hormones in 1994. Around the time Monsanto was developing the hormones, the FDA found—in spite of scientific testimony to the contrary—that there was “no measurable compositional difference” between milk from cows that had been treated with hormones and milk from cows that hadn’t been treated with hormones. As John Robbins points out, that finding, controversial at the time, was overseen by a former Monsanto lawyer who was working at the FDA, who went right back to work for Monsanto after leaving the agency.

After examining the evidence for itself, the court found that milk from cows that have been treated with hormones contains higher levels of the hormone IGF-1. As Robbins points out, the European Commission’s scientific committee said that IGF-1, a growth factor that plays a role in the human endocrine system, substantially increases the risk of breast, colon, and prostate cancer in humans. The court also found that use of the hormones caused cows to produce milk that was higher in fat and lower in protein. And the court found that milk from cows treated with hormones contained higher levels of somatic cells—an indicator of high levels of stress and infection in the cows—which make the milk turn sour more quickly.

While the court’s ruling that milk from cows treated with hormones is different is significant, the ruling also raises the broader issue of whether it is okay to include information about how food was produced on the label. As NPR’s April Fulton reports, the FDA will probably conclude that the flesh of genetically-engineered salmon is no different from the flesh of ordinary salmon. Even if that is true, it raises many of the same issues that treating milk with hormones does. While genetically-engineered salmon have not been injected with hormones, they have been engineered to produce hormones they otherwise wouldn’t. Even if the flesh of the fish does turn out to be the same, genetically engineering fish raises complicated social and environmental issues. The government has no business suppressing information about where our food comes from on the grounds that we are too stupid to understand that information properly. We have a right to the information we need to decide for ourselves what food we want to buy.