What Is Higher Education?

So my post on whether or not higher education is worth it got a lot of responses, mostly negative.

Many of the respondents chimed in through email and want to remain anonymous.

For most people who aren’t geniuses, the college degree is an indispensable credential for entering the world of the middle-class professions. People who get college degrees make lots more money and turn out better in general. People who have the best brands of degrees—such as Harvard’s—do much better still, and so it might be regarded as only fair that such degrees often cost more.

Although plumbers and auto mechanics are often underrated in terms of brains and income, we still have to say that, in a high-tech society, those who do “mental labor” tend always to be improving their position relative to those who do primarily physical labor or labor according to a routine developed by others.

That’s why the top 20% of Americans, even with the economic downturn, still are, in many ways, doing better than ever. It’s also why those in the genuinely middle, middle class—typically without college degrees—seem stuck with lives that are getting more vulnerable and more pathological.

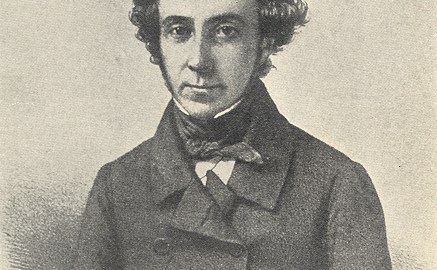

Alexis de Tocqueville, in his hyper-prescient Democracy in America, actually said that he found no higher education in America (in the 1830s). He did find that primary education, in a completely unprecedented way, was available to everyone. Universal literacy is the foundation of a middle-class democracy. Everyone who needs to find a job and make money on his own needs those basic skills.

Someone might say that Tocqueville’s observation ain’t true at all when it comes to America today. Many or most Americans of college age are, in fact, in college of some kind now. And we call college higher education.

But by higher education Tocqueville meant leisurely and attentively reading the best books in their original languages, metaphysics and theology, and theoretical science. He meant the proud and disinterested pursuit of the truth characteristic of Archimedes, Pascal, Plato, Descartes, and Shakespeare. He meant an education that can’t be reduced to an industry or even a technology.

He didn’t mean textbooks, computerized programmed learning, PowerPoint, Scantron tests, group projects, experiential learning, technical skills, or even applied science. He didn’t mean what college means for the overwhelming majority of American students now there.

It’s true that the choice of the technical college major is almost always preceded by a certain number of required courses. But that number is going down, and those courses seem to be more and more detached from the tradition of “liberal education” (or introduction to higher education rightly understood).

Increasingly, the core courses are evaluated according to the acquisition of skills, such as critical thinking, problem solving, effective communication, responsible decision-making, teamwork, and so forth, divorced from what used to be regarded as the content of higher education. And the technical imperative that these “learning outcomes” be measurable is becoming more insistent. (I’m skipping over what’s happened to the social sciences and humanities through political correctness and identity politics.)

It’s far from an altogether bad thing that most American students think of college as a way of acquiring technical skills. They really do need them, after all. And everyone has always known that a life devoted to metaphysics, theology, literature (either reading or writing it), or theoretical physics has always been for the nerdy and uncannily gifted few. Those with such devotion often have a sterile contempt for those who employ scientific knowledge to improve the human condition, and that contempt is not only unproductive but unjust.

If all that’s true (as I’m saying for the sake of argument), then surely the traditional and very expensive trappings of the brick-and-mortar residential college aren’t the best or most efficient way of acquiring the requisite skills. That’s why online, for-profit, and strip-mall methods of educational delivery are becoming more popular. It’s why we were sympathetic when Rick Perry tried to employ all means necessary to drive down the cost of an Aggie degree.

So we return to Tocqueville’s observation that universal American education, although the admirable and indispensable foundation of a free and prosperous middle-class democracy, isn’t higher education.

Tocqueville adds, however, that the Americans were fortunate to have a second foundation for their egalitarian devotion to universal education—the Puritans.

The middle-class view is that we’re all free beings with bodies, responsible for ourselves and especially for securing our own interests. The Puritan or more idealistic form of “all men are created equal” is that we’re all also beings with souls. The Puritan devotion universal education—which was quite real and quite effective—begins with the thought that each of us should be able to read the Bible for him or herself. More later on this.

But for now: Here’s a paraphrase of one Facebook response I got to my original post: Is higher education worth it? To get a job—no. To discover “the good life” (through philosophy and such)—you can’t put a price on THAT.

High-cost college is surely worth it if you discover a different and much better way of life than the one you would have lived without it. (It goes without saying that I’m not talking about a different and better way of making money.) But these days our colleges aren’t all about THAT. If college were mainly about THAT, ironically, it would be a lot cheaper, if not as cheap as Governor Perry has in mind.

Stil, in a country as free as ours, it will always be a misleading exaggeration to say that all education has become enslaved to the imperatives of productivity and technological innovation.