Where Mark Zuckerberg Meets Jean-Luc Godard

What is intellectual property? What is privacy? These questions play out daily now, and those in a position to answer them occasionally shift their views, but the questions surrounding the questions keep pooling in twin twenty-first century eddies: music, and Facebook. We might demonize those who illegally download songs in the same way that we demonize the Facebook founders for reconstructing what we once thought of as privacy, but when will the debates plateau, and who will historians say held the moral high ground? Today’s news that iconic French filmmaker Jean Luc Godard stands behind the idea that “an author has no rights” was an interesting parallel to the presumed philosophical position of Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg on privacy: there is none.

From the New York Times we learn of Godard’s sly stance:

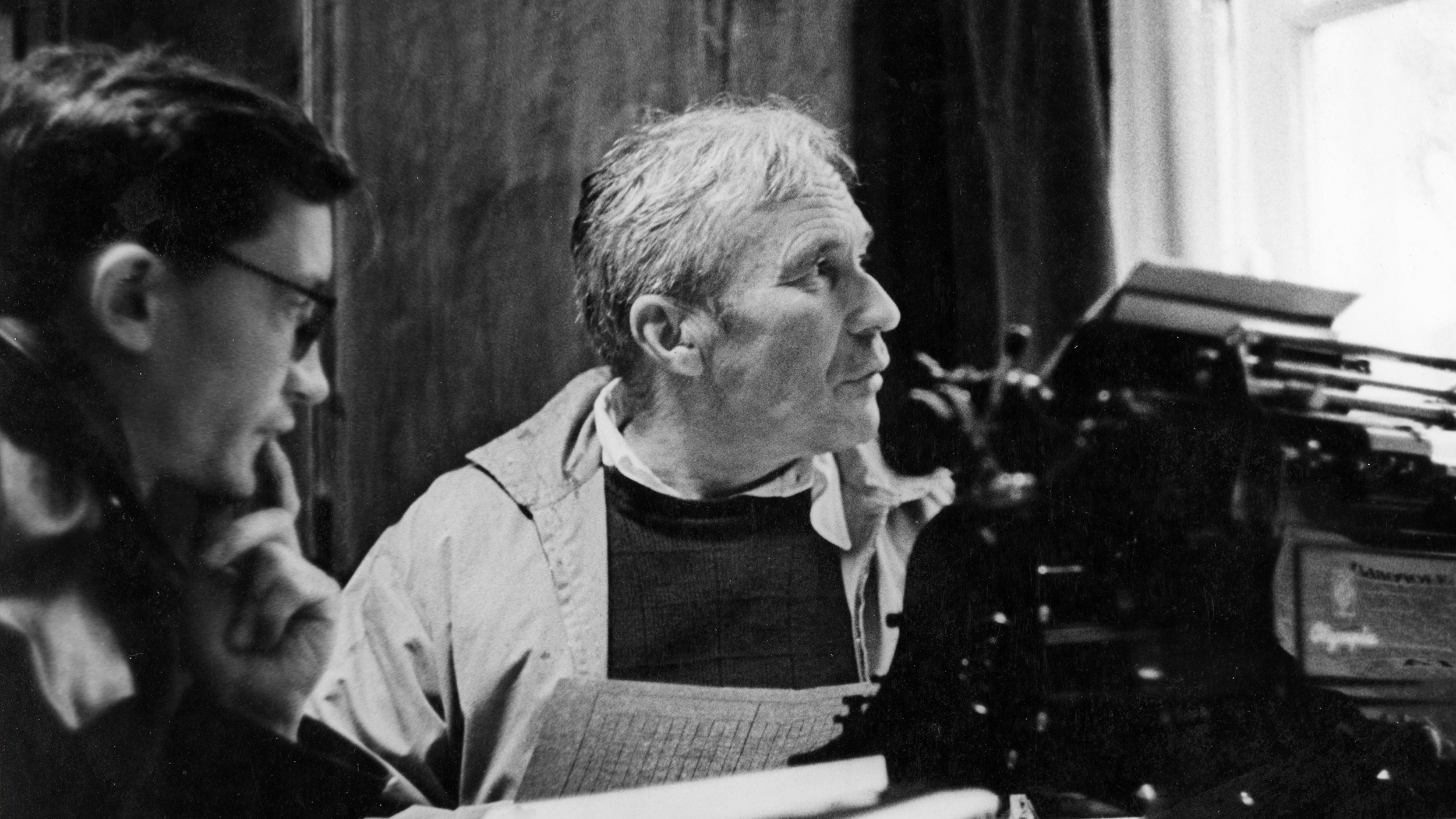

Jean-Luc Godard, the 79-year-old director of movies like “Breathless” and “Alphaville,” has come to the support of James Climent, a photographer who faces a fine of 20,000 euros ($26,520) for violating musical copyrights.

Mr. Climent, who lives in Barjac, a picturesque old town of artists and organic farmers in the Gard region of southern France, wants to take his case to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. The highest French court rejected his last appeal in June, siding with music royalty collection agencies that brought the complaints against Mr. Climent five years ago.

Mr. Climent said Mr. Godard this month donated 1,000 euros to his fund, helping him get him more than halfway toward the 5,000 euros he needs for legal fees and other costs of taking his case to the European Court.

While Mr. Godard’s views on intellectual property are widely shared on the libertarian fringes of the Internet, they might seem surprising coming from a director who, under French law, retains editorial control over his work and derives financial benefit from it.

How interesting. In this, as the Times points out, the current conservative Sarkozy government is ironically aligned against what one might call the cultural elite, as the latter has traditionally been the place where we saw the fiercest proponents of intellectual property. Yet if everything is free, and if artists have only, as Godard put it, “duties,” not “rights,” the battle lines have been re-drawn.

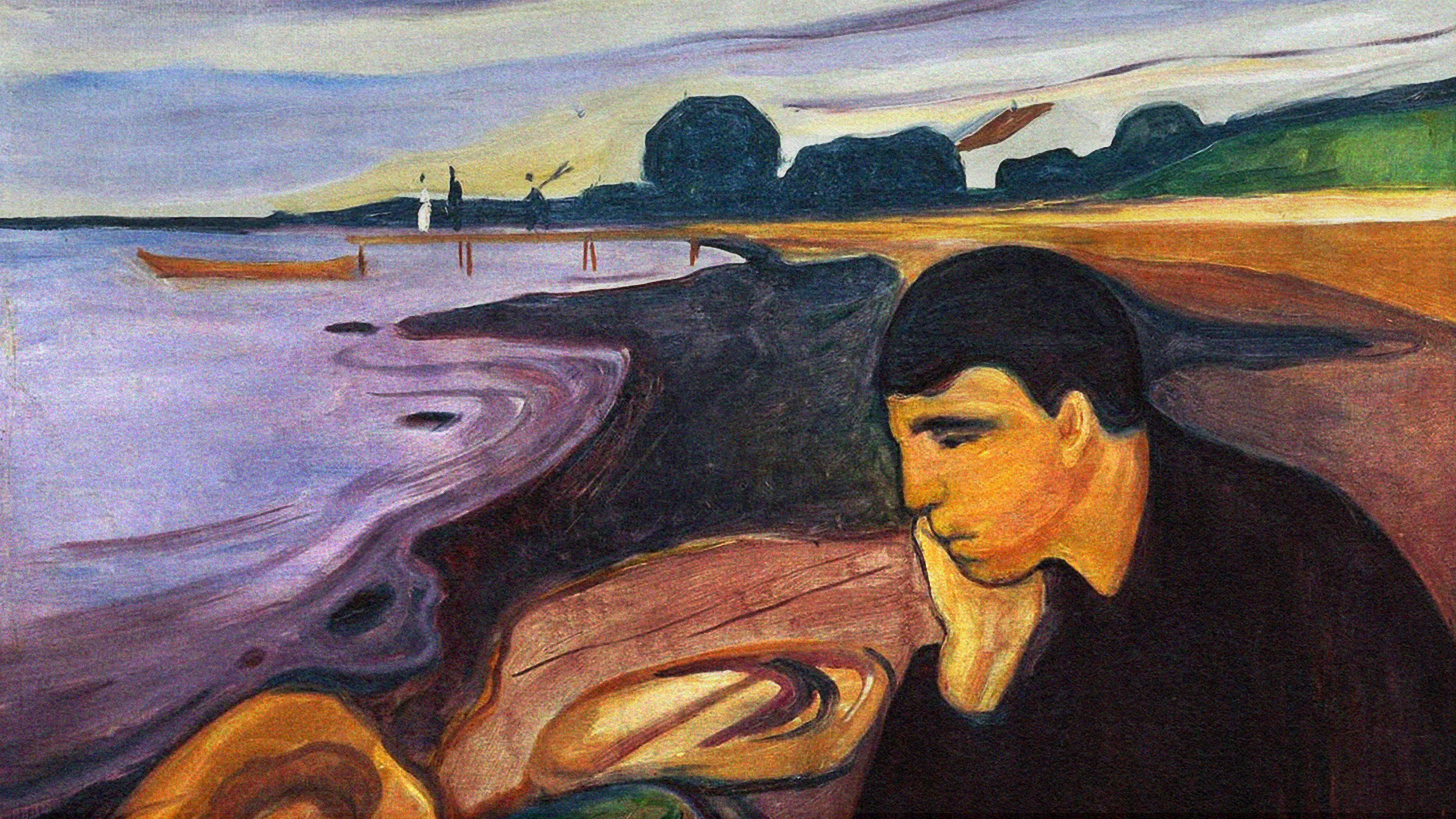

And while Mark Zuckerberg is not an artist per se, and while one might guess that he has never seenAu Bout de Souffle, or ever admired Alain Delon, or even considered the philosophical ramifications of “friendship,” this week was the week of learning more about who Zuckerberg is, and his story is an elegant cultural companion to Godard’s appearance in the press. Godard understood friendship. And, in particular, he understood the confluence of culture and friendship. We don’t expect art from Facebook but perhaps in this we underestimate the organization’s power. Is it a business? A revolution? A game? Where will Zuckerberg stand in fifty years on the rights of artists in society? Only then can clear parallels be drawn.