The case for stopping efforts to contact aliens

- The Netflix series “3 Body Problem” touches upon the risks of humanity broadcasting its presence out into the cosmos.

- The debate around sending messages into space includes ethical concerns about alerting potentially predatory aliens and the technical challenge of messages degrading over long distances.

- Efforts to communicate with extraterrestrials, including the Pioneer plaques and Voyager records, encapsulate Earth’s culture and biology but may be indecipherable to aliens without shared context.

The new Netflix series 3 Body Problem, based on Cixin Liu’s epic science-fiction trilogy, reignites an old debate among researchers concerned with the possibility of extraterrestrial communication. In the fictional account (spoiler ahead!), the trouble starts when one of the characters beams a powerful radio signal out into space. Is that realistic? And is it likely aliens could receive and decode the messages we send?

The answer to the first question is a clear yes. In fact, more than 25 relatively weak signals have already been sent, with the first being a three-word morse code message in 1962. Nearly all of these radio messages targeted specific stars between 17 and 69 light-years away, in the hope that inhabited planets might be orbiting them. One exception is the Arecibo message that was beamed in 1974 toward M13, a globular star cluster approximately 24,000 light-years away. The Morimoto-Hirabayashi Message sent in 1983 should have reached the star Altair in 1999, and there’s been plenty of time for us to receive an answer. So far…nothing.

Apart from these deliberate attempts at communication, radio waves from our transmitters have been leaking out into space in all directions since the early 1930s. More recently, nonradio messages have been attached to outgoing spacecraft, the most famous of which are the two Pioneer plaques (which included a map to show the aliens where to find us) and the Golden Records mounted to the two Voyager spacecraft launched in 1977, which have now reached interstellar space. These digitized messages include selected sounds and images to highlight the diversity of life and culture on Earth, as well as depictions of our solar system and its planets, and human anatomy and reproduction.

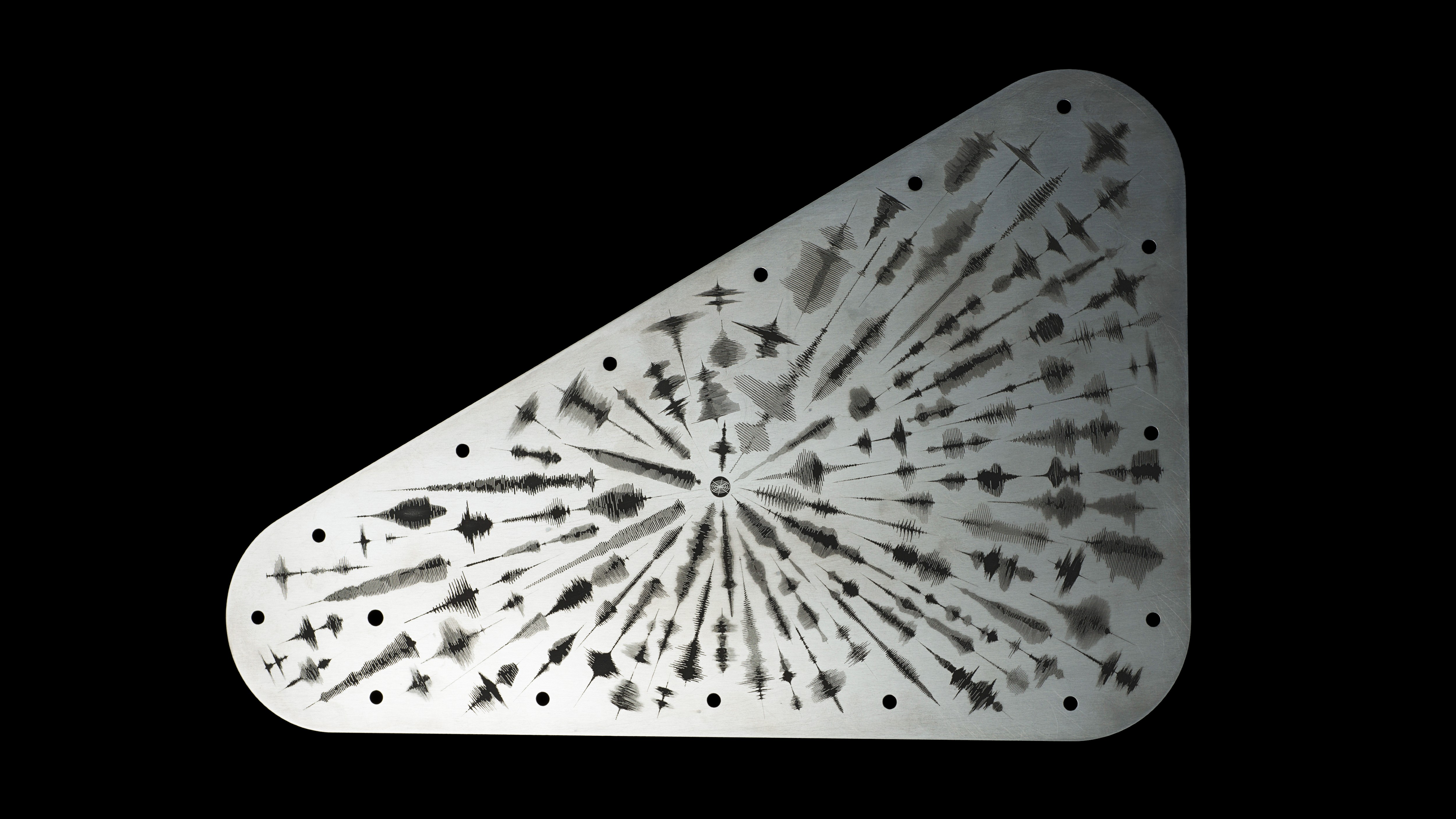

Similar projects continue today. A triangular metal plate containing 2.6 million names submitted by the public, plus recordings of the word “water” spoken in 103 languages, is set to be launched to Jupiter on the Europa Clipper mission later this year. Currently on Mars, the Perseverance rover is conducting exploration work carrying silicon chips with nearly 11 million names stenciled on them.

Of course, since no one really believes aliens are hiding on Mars or Europa, these efforts are more about how we frame our culture to ourselves than communicating with aliens. Nevertheless, all the projects listed above are lumped together under the general term “active SETI,” also called METI — meaning attempts to send messages out, as opposed to SETI, which listens for possible messages coming in.

The risks of broadcasting our presence

Not everyone likes the idea of METI. Stephen Hawking was among those who went on record saying it was foolhardy to alert aliens to our presence: It would be like sheep calling out for the wolf because any intelligent extraterrestrial is likely to be a social predator like us. Such a species would likely have predatory roots because the evolutionary trait of intelligence is promoted if you have to hunt for your food. A lion has to be smarter than a grazing antelope, which feeds on grasses. A wolf has to be smarter than a lion. Because it’s not as strong, it has to anticipate the prey’s next move and communicate with other wolves in the pack during hunting.

While intelligent aliens would have required a certain amount of aggression in their past to make it to the top of the food chain, they also would need to be social, and therefore not too aggressive. Our close relatives, chimpanzees, with whom we share 99% of our genes, are characterized by male competition, aggression, and instigation of fear. Compare this to our hominid ancestors, who had reduced levels of aggression and more stable social arrangements, meaning that outsiders were more tolerated and innovations (such as the use of new tools) were more easily accepted by the community.

Even with this more benign lineage, human history is marred by episodes of violence and savagery. Most of the time, though, we get along with each other, often for long periods. Collaboration prevails over competition. Without cooperation, complex societies wouldn’t form. It would likely be the same for extraterrestrials, though their specific social structure may look very different. Their social structure could be more like eusociality, an elaborate form of social organization seen in bees, ants, termite colonies, and even some mammal species, such as the naked mole rat.

There is a drawback to eusociality, however. Much of the individual organism’s behavior is genetically programmed, and there is little ability to adapt to changing environmental conditions. A more individualistic approach to social structure, as with humans, seems more advantageous, even though individual egos can easily cause harm, or, in the nuclear age, even self-destruction.

It’s possible that spacefaring extraterrestrial civilizations evolved to overcome their early aggressive tendencies, though it’s unlikely they would lose them entirely. Even if they did, conflicts could still arise from misunderstandings or the need to survive. Although science-fiction aliens often are shown invading Earth, I don´t think that would be very likely. The only special thing about our planet is its biology. If mineral resources are what the aliens want, the better option would be to get them from an asteroid or uninhabited moon, without having to fight for them. Earth’s amazing biodiversity is critical to our own survival but may not be tempting for an ETI (extraterrestrial intelligence). Aliens are likely to find our biosphere toxic since they’d have no immunity to all the bacteria and viruses that we humans have coexisted with for millions of years (think War of the Worlds).

Given the huge risks (and possible rewards) associated with contacting an extraterrestrial civilization, it seems odd that anyone can send out a radio message at any time, without asking permission from anyone. A group associated with the SETI Institute raised this concern back in 2015, stating that “the decision whether or not to transmit must be based upon a worldwide consensus, and not a decision based upon the wishes of a few individuals with access to powerful communications equipment. We strongly encourage vigorous international debate by a broadly representative body prior to engaging further in this activity.” Sadly, there’s been no progress toward making that happen.

Most of the messages sent to date have been in the form of radio waves. These, of course, get weaker the farther they travel into space. The signal strength decreases with the square of the distance from Earth, meaning that if the distance doubles, the signal strength drops by a factor of four. In addition, over long distances, the interstellar medium distorts the signals, meaning that any alien recipients would likely have difficulty distinguishing the transmission from random noise unless a huge power source is used to transmit as in 3 Body Problem, which hasn’t been the case so far.

Could aliens decode our messages?

Let’s say, though, that an ETI did receive our message loud and clear. It’s doubtful they could make sense of it. Without being told the meaning of the message beforehand, it’s even very difficult for most Earthlings to figure out (try to interpret all the drawings in the Pioneer plaque, for example, without reading the explanation first). I have the advantage of coming from the same cultural background as the message senders, but would find it very difficult myself. What chance would aliens have?

Even if they’re able to decipher a relatively short and simple message, extended conversations with aliens may prove impossible. Mathematical equations are one thing (would spacefaring aliens know them already?). But as for communicating anything related to human experience, we haven’t yet figured out how to effectively talk with dolphins, a clearly intelligent species related to us. Even some ancient human languages haven’t been decoded yet.

In short, the chances that our radio message could actually reach an ETI are very low, and the chances of them understanding it even lower — that is, unless they’re already here and have been studying us. In that case, it really doesn’t matter whether we transmit or not. That’s the most likely scenario if the Zoo hypothesis is correct, which assumes that an ETI would choose not to interfere with the natural evolution of a developing culture (similar to Star Trek’s “prime directive”). The other possibility, as pointed out in a recent Nature Astronomy paper by Ian Crawford and me, is that there is nobody else — or hardly anyone else — in our part of the Universe. In that case, it also doesn’t matter whether we transmit or not, because there’s no one around to hear us. Since we don’t know which hypothesis is correct and the possibility exists that both are wrong, we may want to be cautious about signaling our presence to extraterrestrial civilizations — just in case the authors of 3 Body Problem are right.