Synecdoche: what a psychological drama can teach us about life and death

Credit: Kenny Orr via Unsplash

- Following the film’s release in 2008, critics worried Kaufman may have finally gotten too meta for his own good.

- On the contrary, this confusing story about the inevitability of death contains a simple lesson about the meaning of life.

- Death, like birth, is one of the few things all human beings have in common. It should not be feared but contemplated.

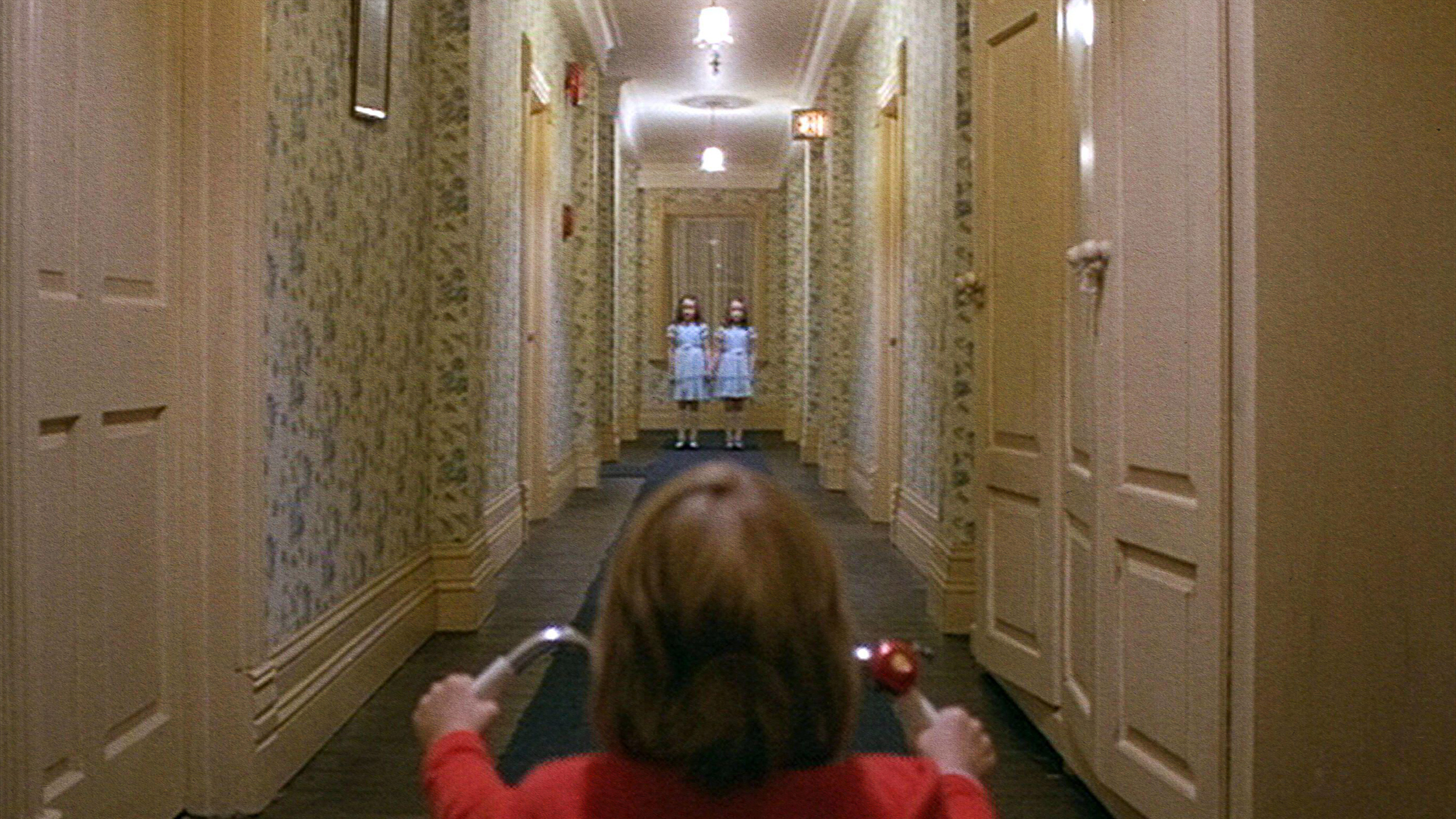

When screenwriter Charlie Kaufman was asked to make a horror film, he began by asking himself a straightforward question: what is the scariest thing imaginable? In hindsight, it should come as no surprise that the creator of Being John Malkovich and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind refused to settle for something predictable like “scary clowns” or “bloodthirsty shark.” What terrified Kaufman was not some dreamt-up monster chasing him down a dark alley but the very real fact that he — like everyone else — will one day, inevitably and indefinitely, cease to exist.

The film that Kaufman built around this premise is called Synecdoche, New York. Set in an upstate town whose name is a spoof of Schenectady, it tells the life story of an ambitious but neurotic theater director named Caden. When his estranged wife and daughter move to Germany, Caden processes his grief and growing existential dread by staging a play about himself staging a play. Determined to tell nothing but the truth, he not only hires actors to play himself and his loved ones but also actors to play the actors, and actors to play the actors that are playing the actors. If you know Kaufman, you can guess where this is going.

Those who have seen Synecdoche frequently cite it as one of the best albeit most depressing films ever made.

Synecdoche, which came out in 2008 and also marks Kaufman’s directorial debut, quickly became known as his most confusing project to date, more so than last year’s I’m Thinking of Ending Things. As the film goes on, its story becomes increasingly surreal, mirroring the devastating toll Caden’s production takes on his relationships and mental health. The film’s convoluted structure was not received well by critics, who feared that Kaufman had at long last turned too meta for his own good. Yet underneath this convoluted tale about the inevitability of death lies a simple, relatable message about the meaning of life.

Most films try to distract audiences from their real-world problems, and death — though often depicted on-screen — is often overcome by love or friendship. With Synecdoche, Kaufman wanted to tell a story devoid of sugarcoating. “What was once before you, an exciting, mysterious future,” the film’s screenplay reads, “is now behind you. You realize you are not special. You struggled into existence and are now silently slipping out of it (…) You think only about driving. Not coming from any place, not arriving any place. Just driving.”

Memento mori

In medieval times, religious artists and thinkers popularized the phrase memento mori (“remember that you die”) under the belief that mindfulness of our own death inspired us to live better, more meaningful lives, yet this is not how things work out in Synecdoche. An incorrigible hypochondriac, Caden spends hours searching his body for traces of the disease destined to end his life. His fear of dying is so great that it borders on mania, causing him to imagine health problems he does not have. His last name, Cotard, is an obvious reference to Cotard syndrome: a rare neuropsychiatric delusion where a person believes they are already dead.

Rather than inspiring sympathy toward his fellow mortals, Caden’s anxiety compels him to act vainly and selfishly. In between staging his play, settling his divorce, and swallowing an ever-increasing number of prescription pills, Caden tends to forget that the people around him will meet the same cruel fate he will. When a woman who used to be in love with him tells him that she is happily married, he tears up and confesses that he does not want her to be happy. In Kaufman’s eyes, relationships are formed only when two equally lonely people happen to find each other at the right time.

For reasons that should now be clear, those who have seen Synecdoche frequently cite it as one of the best albeit most depressing films ever made. On YouTube and Reddit, fans rave about Kaufman’s well-rounded characters, mind-boggling narrative structure, and laser-precision dialogue. But the appeal of this masterpiece runs deeper. Unable to erase its suffocating atmosphere and haunting message from their memory, audiences revisit Synecdoche over and over again — often involuntarily. Like death itself, the movie’s looming shadow — once perceived — becomes impossible ignore.

If you are going through a bout of melancholy, you may want to hold off on Synecdoche. It is, after all, not exactly the type of movie that makes you feel good. This was not Kaufman’s intention, even if there are scenes when it seems like it. Looking at the film from the perspective of a psychologist, it is clear that many of Kaufman’s characters are severely depressed but refuse to work on themselves in a healthy way. While the odds are stacked against Caden from the start, his obsession and self-pity end up serving him no purpose. At the end of the day, Synecdoche is as much a eulogy as it is a cautionary tale.

While literary giants like Leo Tolstoy had plenty to say about how people should behave, Kaufman never claimed he had the answers to life’s many mysteries. When asked to spill the secrets of his trade by BAFTA, he started his speech by saying that he had nothing to teach. “Say who you are,” was his only advice. “Really say it, in your life and in your work. Tell someone out there — someone who is lost, someone not yet born, someone who won’t be born for 500 years. Your writing will be a record of your time. It can’t help but be. But if you’re honest, you will help that person be less lonely in their world.”

This quotation serves as an introduction to just about every Kaufman film, but its echoes are especially prevalent in Synecdoche. Pushed toward the back of our minds, our instinctive and universal fear of death is left to grow and fester. By putting this fear — which often brings out the darkest, most pathetic parts of ourselves — on screen, Kaufman is giving us what his characters so desperately need but never seem to find: a sense of genuine connection between the people that watch his movies and feel the pain he tries to emulate in his writing.