- In microgravity, brain fluids behave differently, winding up in different places in the skull.

- Astronauts’ white matter is affected by being in space and weakens their back-home sense of balance.

- The study hints at our brains’ possible ability to adapt to space conditions.

As humankind evolved, there were a few givens: The presence of oxygen for one, and also gravity. These are both, of course, absent in space. Health data from recent space missions has exposed a variety of ways our bodies go a bit off the rails without the gravity to which we’re accustomed. Scientists already knew about the dangers of prolonged exposure to radiation, eyeball-shape changes and vision issues, as well as cardiac issues and muscle- and bone-mass loss. Now a study published in JAMA Neurology provides new details on how space flight negatively affects the human brain, and in particular its white matter.

University of Florida’s Rachael Seidler, an applied physiologist and kinesiologist, says, “The deterioration was the same type you’d expect to see with aging, but happened over a much shorter period of time. The findings could help explain why some astronauts have balance and coordination problems after returning to Earth.” The effect was especially pronounced among those who’d spent more time in orbit, as Seidler tellsPopular Science: “They were greater with longer spaceflight mission durations, and larger brain changes were correlated with greater balance declines.”

Identical twins Mark, left, and Scott Kelly. Scott’s face became bloated from the migration of fluids to his head during his year abroad the ISS.

Image source: NASA

Microgravity fluid behavior

The study is based on diffusion MRI (dMRI) brain scans made of 15 NASA astronauts. (Seidler was joined in the study by colleague Jessica Lee, and by NASA’s Johnson Space Center.) Scans had been performed prior to the astronauts’ missions. Seven of the subjects were space shuttle personnel aloft for less than 30 days, and the remaining eight had been assigned to the ISS for longer missions up to 200 days. The median age of the 12 men and three women was 47.2. Their brains were scanned again, post-flight.

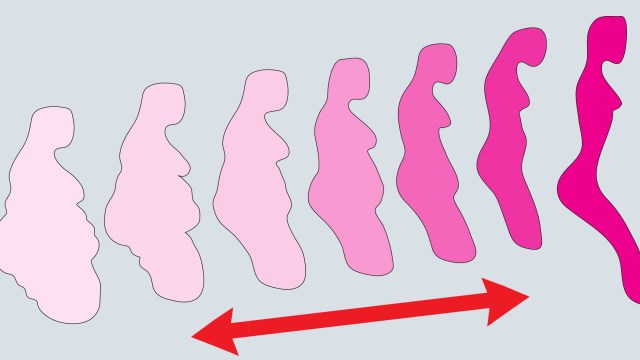

And there’s the fluid. “We know, “says Seidler, “that fluid shifts toward the head in space. When you see photos and video of astronauts, their faces often look puffy, because gravity isn’t pulling fluids down into the body.” The scans bore this out. The liquid could be seen pooled around the base of the brain, causing the brain to float higher in the skull with less fluid protecting it on top than it would have on Earth. It’s possible that microgravity pulls additional cerebrospinal fluid into astronauts’ brains.

The fluid misplacement could be causing vision issues. Seidler suggests that “it could be pressure on the optic nerve or that the brain is sort of tugging on the optic nerve because it’s floating higher in the skull.”

Even more concerning were the changes to the astronauts’ white-matter areas controlling movement and the processing of sensory information.

Another, possibly encouraging, finding is that there were changes in the cerebellum of short-term flyers, but not the others. This may mean that being in space longer gives the cerebellum — and by extension the whole brain — time to adapt, an especially intriguing notion considering humankind’s hopes of long-term missions.

Chris Cassidy of NASA being carried to the medical tent just after returning to Earth.

Image source: NASA

Back to normal

Fortunately, the balance issues astronauts experience after coming home eventually tend to sort themselves out. However, it’s unclear that such resolutions reflect a healing of the deteriorated white matter, or if the flyers are merely getting used to its altered state.

Seidler is looking toward further study that tracks the longer-term story, with a third set of scans made six months after returning to Earth. Understanding the extent to which the human brain can return to normal after space flight will be an important consideration in the planning of longer missions and before introducing residents of Earth to space tourism.