Why humans struggled to make ‘f’ and ‘v’ sounds until farming came along

Blasi et al.

- A new study suggests that the f and v sounds were made easier to pronounce by the change in our diets the invention of farming made possible.

- The idea isn’t a new one, but is only now being taken seriously.

- Even today, many hunter-gather cultures lack labiodentals in their languages.

The Neolithic Revolution fundamentally changed how humanity went about the business of surviving. With the rise of farming, humans no longer had to travel into inclement climates following the migration of animals, their former pervasive food source. Instead, fields of grain were cultivated, and, in turn, permanent settlements were created — civilization was established.

But while the social and economic effects of this revolution are apparent, other significant effects of switching to farming on our daily lives are more subtle. Among them is a minor change in our anatomy that allows us to make the “f” and “v” sounds.

How a change in diet changed everything

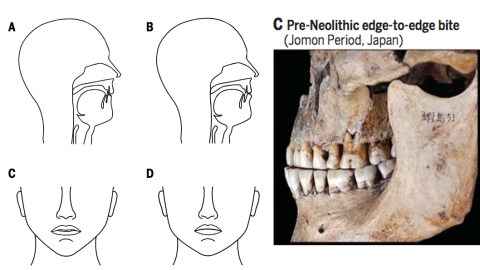

F and V are labiodentals, which means to make their sounds you have to raise your lower lip to your top teeth. This is easy enough with a slight overbite, but if your teeth are closer to being even, as the skulls of our ancient ancestors suggest was once more common, the sounds become harder to make.

Decades ago, the linguist Charles Hockett pointed out that societies with softer foods had more labiodentals in their languages than societies that were still hunting and gathering. He hypothesized that the shift to farming might have allowed for this, as softer foods require smaller lower jaws than hard foods do.

Constantly eating foods that are hard or raw is tough on your teeth. Over time, it can lead to them lining up more edge to edge. Soft diets also put less pressure on your jaw, which can lead to a shorter mandible which itself can contribute to a slight overbite or overjet.

In a society where none of the food is softened by processing, most people are going to end up with no overbite at all by the time they’re adults. In a society with softer, processed foods, such as grains, an overbite as an adult becomes possible and eventually the standard. This, more than anything, makes a language that uses labiodentals practical.

His idea never really caught on, and a new study out of the University of Zurich by Dr. Balthasar Bickel, Steven Moran, Damián Blasi, and others set out to prove Dr. Hockett wrong. It accidentally found he was onto something.

Blasi et al, David Frayer, Department of Anthropology, University of Kansas, USA, Mihai Constantinescu, Institutul de Antropologie “Fr. J. Rainer,” Bucharest, Romania, Karin Wiltschke-Schrotta, Department of Anthropology, Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, Austria.

Three skulls showing the evolution of the adult overbite. On the left is the skull of a Paleolithic woman, notice the edge-to-edge teeth contact. In the center is a woman from the Mesolithic era with a similar smile. On the right we see the overbite of a Bronze Age male.

What, how did they do that?

The scientists used biomechanical simulations to learn how much easier it is to pronounce labiodentals with a slight overbite than with perfectly even teeth. As it turns out, it helps a lot, the simulated jaws that had perfectly even teeth needed a third more energy to pronounce their f and v sounds.

If it takes that much energy and contortion of the mouth to make those sounds, you can imagine why some languages might never have bothered to incorporate them.

The authors also reviewed data on the languages of hunter-gather societies and found they only used labiodentals about a quarter as much as languages used by agricultural communities. Skulls of humans from both before and after the agrarian revolution were examined again and an increase in the number of overbites as the availability of softer foods improved was found.

For good measure, they then compared daughter languages — languages that descend from others — to their older counterparts and found that labiodentals were more frequent in the younger languages.

This is cool and all, but what use does this have?

These findings could severely impact a few theories in linguistics. Co-author Steven Moran explained that the results show that our idea of humans being able to make the same sounds since we started speaking is now up for debate:

“The set of speech sounds we use has not necessarily remained stable since the emergence of our species, but rather the immense diversity of speech sounds that we find today is the product of a complex interplay of factors involving biological change and cultural evolution.”

Sean Roberts of the University of Bristol told New Scientist that the findings were “exciting” and explained them in terms of how linguists were going to be using the data for further research: “For the first time, we can look at patterns in global data and spot new relationships between the way we speak and the way we live.”

The shift to agriculture changed not only how we live, but how we can express ourselves. While introducing more labiodentals into the world probably isn’t as big a deal as making civilization possible, it still shows that the worlds we humans create can change us more than we would ever think they could.