What is an immunity passport and could it work?

TOLGA AKMEN/AFP via Getty Images

Weeks into lockdown and with economic indicators signalling a deep global recession, governments around the world are searching for ways to get their countries back up and running.

But emerging from a cocooned state could risk a second spike of coronavirus infections as people start mixing once more. Among the measures being considered by governments including Chile, Germany, Italy, Britain and the US are immunity passports – a form of documentation given to those who have recovered from COVID-19.

In Chile, which looks set to become the first country to put such a scheme into action, the so-called “release certificate” would free holders from all types of quarantine or restriction, Chilean Health Minister Jaime Mañalich said in April.

Image: Statista

Premature release?

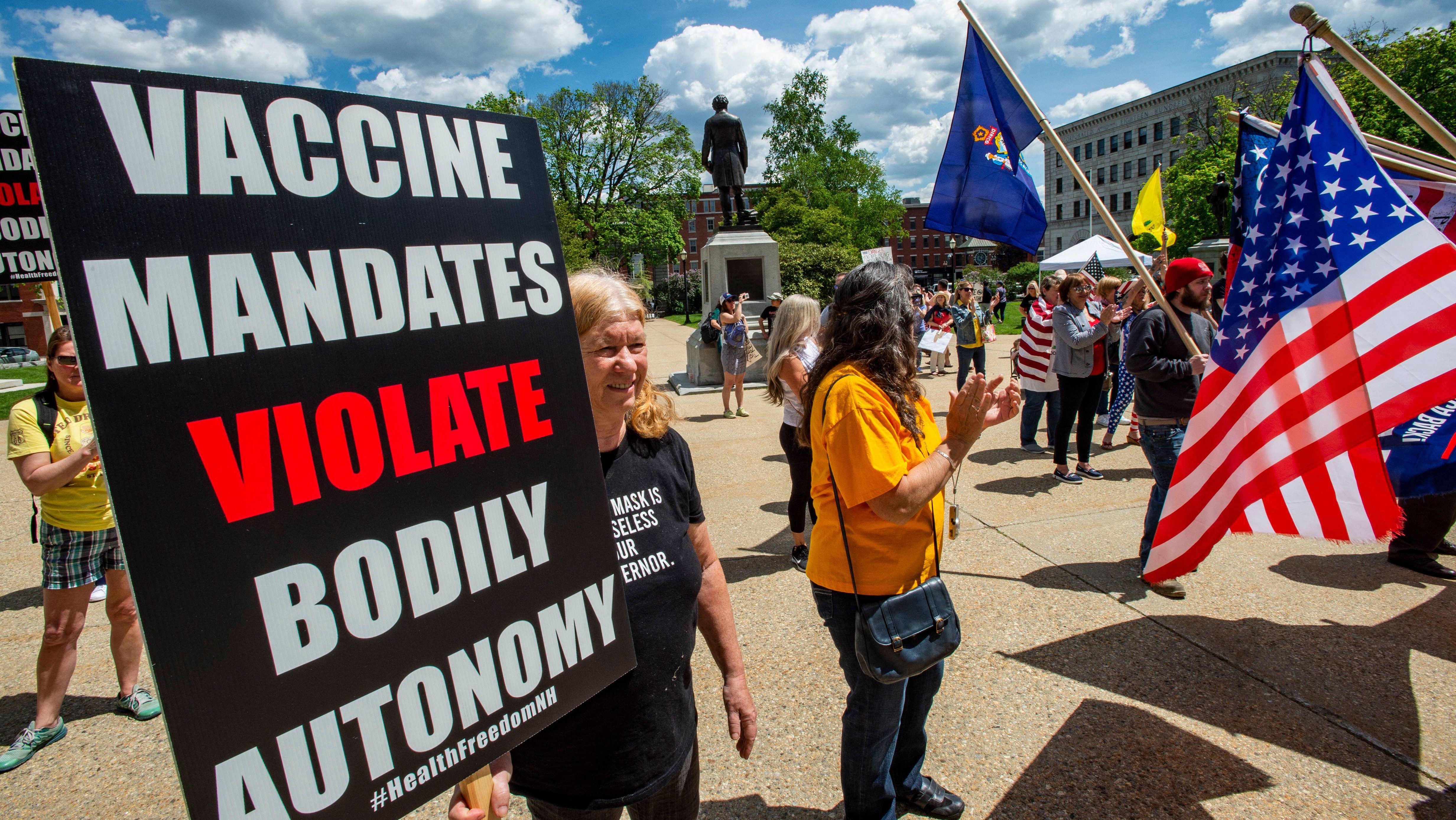

But the idea has proved contentious, with the World Health Organization (WHO) among those voicing criticism. The root of the concern for many is the unknown degree to which past infection confers future immunity. Until it is understood whether or not people can be reinfected with the disease, and how long any immunity lasts for, the move may be premature.

In Chile’s case, the certificate will expire three months after a confirmed infected person has recovered. After this point, they will be considered to have the same risk of infection as anyone else. The government hopes the certificates will encourage diagnosed individuals to report results to the health ministry.

The WHO also raises questions about the validity of results from some of the tests on the market, which it says are not sufficiently sensitive or accurate.

False positives could lead people to think that they are safe from future infection, despite never having had the disease. False negatives would also mean infected people might fail to self-isolate. Advice from the WHO is that immunity certificates may in fact risk continued transmission of the virus, and lead to people ignoring public health advice.

Image: Statista

This could be a particular cause for concern given a number of recent studies have demonstrated that a comparatively small population has been infected so far, leaving the vast majority still vulnerable. Many countries are also bowing under the weight of the amount of testing required.

Placing a value on recovery

Some experts think enforcing two-tier restrictions on who can and cannot socialize or go to work also raises legal and practical concerns, and that it could have the adverse effect of incentivizing people to seek out infection to avoid being excluded.

And as such existing inequalities could worsen. Not least the economic divide, potentially exaggerated by some being excluded from work when others aren’t.

“By replicating existing inequities, use of immunity passports would exacerbate the harm inflicted by COVID-19 on already vulnerable populations,” Alexandra Phelan, a member of the Center for Global Health Science and Security at Georgetown University, writes in The Lancet. Because of this, she says, they would be ripe for corruption.

Phelan also says immunity passports could risk providing some governments with an “apparent quick fix” that could result in them failing to adopt economic policies to protect health and welfare.

Alongside advances in vaccines and creating the infrastructure to deliver them, investment in testing and tracing is seen by many as key to limiting further spread of the virus. The International Labour Organization is among the bodies that say this could play an effective role in getting people back to work.

Reprinted with permission of the World Economic Forum. Read the original article.