Increased air travel may decrease the chances of a global pandemic

- The more exposed we are to each other, the less surprising a pathogen will be to our bodies.

- Terrorism, high blood pressure, and staffing issues threaten to derail progress.

- Pursuing global health has to be an active choice.

Part of the anxiety in watching the 2011 film Contagion hinges on members of the CDC watching the map of the world itself: the world is so large and filled with so much detail — nooks, corners, and endless blind alleys — that it felt difficult to get a handle on where the next outbreak would flare up. All this was occuring because a woman travelled back to Chicago from Hong Kong.

The movie is a cultural expression wedded to a particular fear — a fear we saw expressed when screenings were issued for flights coming from countries on the African continent that had no cases of ebola whatsoever during the ebola outbreak, perhaps culminating in the obscene spectacle of then-Governor Chris Christie sending a nurse to sit in a tent outside a hospital in New Jersey for two days.

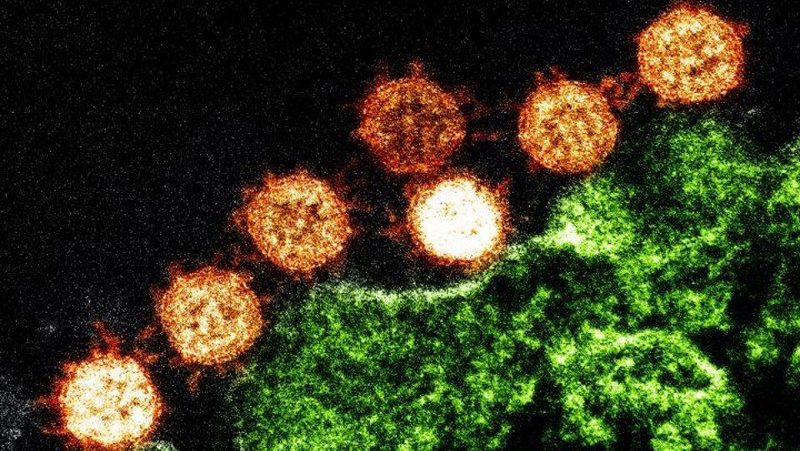

But here’s the double-edged thing about the film and its message: studies have recently been released to say that increased air travel may decrease the chances of a global pandemic. The caveat is that global progress in health isn’t inevitable.

The first study — written mostly by academics from Oxford — observes that frequent travel can reduce the impact of deadly outbreaks because communities exposed to each other consistently because of travel are more frequently exposed to low-risk strains. The authors of the paper argue that this “may be a factor contributing to the absence of a global pandemic as severe as the 1918 influenza pandemic in the century since.”

One example they cite: the H1N1 outbreak in 2009. It didn’t have the expected impact because of something called ‘cross immunity,’ where one person typically susceptible to disease ABC is exposed to someone typically susceptible to disease XYZ. That pre-exposure meant that “pathogen dynamics and the structures of pathogen populations” were impacted, lessened, and changed. New pathogens may move quickly through a global world, but pathogens we already know won’t move as quickly nor be as effective. The population has already built up some kind of immunity.

The model devised by the academics in this paper is— from the admission of the authors themselves — as ‘simple’ a model as could be devised.

But even if the math holds true — and has already been flagged — progress isn’t inevitable. Some of the highlights from the 2018 Global Burden of Disease study note that half of countries are “estimated to face shortfall in healthcare workforce – with 47% of having fewer than 10 doctors to serve 10,000 people and 46% having fewer than 30 nurses or midwives to serve 10,000 people.”

Not addressing those needs means that other problems flagged by the report are all the more likelier to continue. Stepping up to address these issues falls within the realm of agency and choice.

The math of pursuing better global health through air travel could well hold true, but we have to make it hold true by virtue of our actions.