Do doctors warn patients enough about opioids?

(DrugAbuse.com)

- More than 130 people die every day from opioid-related overdoses, and some 11.4 million Americans have an opioid disorder.

- Americans remain wary of opioids and want more guidance; about a third of doctors need to explain options better.

- Patients have to pro-actively question subscribing physicians.

The statistics that describe America’s opioid epidemic are sobering. According to Health and Human Services numbers released in May 2018, more than 130 people die every day from opioid-related overdoses, and some 11.4 million Americans have an opioid disorder. Many in the medical community are trying harder on their end to reduce opioid prescriptions, though perhaps not all. And many patients remain uncomfortable taking the drugs, about 30%, according to 1,011 survey responses gathered by DrugAbuse.com for its recently published Painkiller Protocols visualizations. Though the majority of doctors are doing an adequate job, there’s still about a third of them who could be doing more.

All infographics in this article are by DrugAbuse.com.

How uncomfortable we are about getting started with opioids

Comfort with opioids is, to some extent, generational, with baby boomers being the most concerned about beginning a course, at 39%, and millennials somewhat more okay with going on pain meds, at 29%. Overall, 54% aren’t really concerned one way or another. But still, a third of people surveyed have concerns. Part of what leaves people uneasy is the degree to which their doctors have screened them as candidates for an opioid prescription—over a third were never asked the questions the accepted guidelines recommend prior to prescribing.

What did the doctor explain?

While doctors overwhelmingly explain how to use the opioids they prescribe, about 40% of of them poorly lay out, or fail to mention altogether, three things a patient should know:

- non-opioid alternatives

- risks of taking the medications

- possible side effects.

Are opioid prescriptions being controlled via treatment plans?

Once doctors decide to prescribe opioids, about half establish a plan that includes a time limit on patient use of opioids. Slightly more doctors do this for longer-term prescriptions. Again, though, many non-opioid treatment plans seem not to be taken quite as seriously, nor, again, are doctors asking their patients at least one key question patients expect to be asked before proceeding. All of this depends on the type of pain that a patient needs addressed.

(DrugAbuse.com)

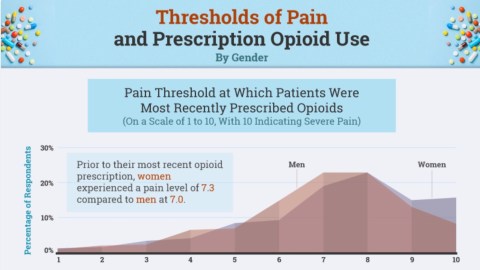

Pain and opioids

Prescriptions are doled out, naturally, according to the intensity of pain being experienced. Using a scale of 1 to 10, where 10 is the most extreme level of pain, women had to be at a pain level of 7.3 before getting a scrip. That’s higher than the 7.0 that triggered meds for men—one would expect this to be more equal. Men and women have different expectations about when their pain merits treatment, too, with men wanting relief sooner—at a pain level of 6.6—and women wanting to hold out until it reaches 7.7.

In any event, the differences on the impact of opioids on women and men aren’t clear, seesawing back and forth depending on the specific drug.

How appropriate are prescribed opioid levels?

By and large, respondents felt they were prescribed the right amount of pain relief, whether for acute or chronic pain. Opioids prescribed after childbirth and for oral pain felt for some as if a milder dose would have been enough, though roughly a third of those with nerve or muscle pain felt they could have used a stronger prescription.

(DrugAbuse.com)

After the pain

So what do you do with left-over opioids, after they’re no longer needed? The proper approach is to take them to an authorized drug collection site, where they can be safely disposed of . Only about 12% actually do this. Mostly we hold on to them “just in case”—12% of us do repurpose them for other pain—or we just toss them in the trash. 1% sell the extras.