Mini-brains may already be sentient and suffering, scientists warn

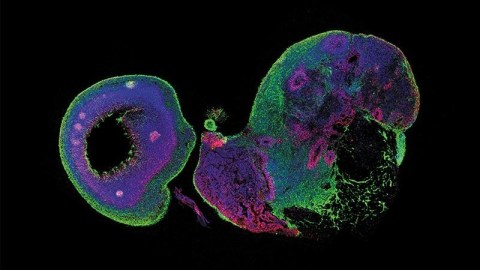

Credit: M. Lancaster/MRC-LMB

- Mini-brains (also called organoids) are tiny lumps of tissue capable of generating rudimentary neural activity.

- Neuroscientists use mini-brains to conduct research and experiments that help them learn about the brain.

- As scientists generate increasingly complex mini-brains, however, some are concerned they might be experiencing pain.

Neuroscientists are “perilously close” to crossing serious ethical lines by experimenting with mini-brains that might be complex enough to feel pain. In fact, experiments with mini-brains (also called organoids) might have already crossed those lines.

“If there’s even a possibility of the organoid being sentient, we could be crossing that line,” Elan Ohayon, the director of the Green Neuroscience Laboratory in San Diego, California, told The Guardian. “We don’t want people doing research where there is potential for something to suffer.”

On Monday, Ohayon and his colleagues presented a computational study at Neuroscience 2019, the world’s largest annual meeting of neuroscientists. The study aimed to establish guidelines for scientists to determine when exactly a mini-brain develops consciousness.

“Assessment informed by the models and associated dynamics suggests that current organoid research is perilously close to crossing this ethical Rubicon and may have already done so,” the paper states. “Despite the field’s perception that the complexity and diversity of cellular elements in vivo remains unmatched by today’s organoids, current cultures are already isomorphic to sentient brain structure and activity in critical domains and so may be capable of supporting sentient activity and behavior.”

Stand-ins for human brains

Mini-brains are tiny lumps of tissue made from stem cells that are capable of generating rudimentary neural activity, and researchers use them in neuroscience experiments. The main benefit of mini-brains is that scientists can conduct important research that sheds light on the human brain all without having to use actual human or animal brains.

As Big Think’s Robby Berman noted in March, mini-brains are relatively rudimentary. The most advanced organoid possesses a couple million neurons — twice that of a cockroach, but far fewer than an adult zebrafish. The human brain, meanwhile, has some 100 billion neurons. But mini-brains are becoming more complex.

Smarter mini-brains

A 2018 study showed that organoids implanted in mouse brains are capable of attaching to the animal’s blood supply and sprouting new connections. In another recent study, researchers created a mini-brain with retinal cells, which are the neurons that process visual information. In August, a paper published in Cell Stem Cell described how researchers developed an organoid that is capable of producing brain waves similar to those of premature human babies.

“We never had a brain organoid that can function like the human brain,” biologist and researcher Alysson Muotri told Discover Magazine. “The electrical activity of these brain organoids are emitting something we see during normal human development. So, it’s a strong indication that what we have should work and function like the human brain.”

The need for clearer definitions of consciousness

Some scientists think that mini-brains are still too rudimentary to experience anything like what humans would call pain, and therefore the community doesn’t need to worry about creating a nightmarish torture scenario for mini-brains. But others argue that scientists should establish clear guidelines for consciousness so can stop experiments before they effectively create new way for beings to suffer.

“We don’t really know actually where this is all going,” Patricia Churchland, a Salk Institute professor emerita who studies the linkage between philosophy and neuroscience, told the San Diego Union-Tribune. “It’s very, very difficult to predict the future in science, as in baseball.”

In the computational study presented on Monday, the researchers discussed five domains through which consciousness might be defined: [1] compositional (e.g., atomic, molecular), [2] causal (e.g., genetic, evolutionary), [3] anatomical (e.g., cellular, network geometry, brain regions), [4] physiological (e.g., cellular, network, whole brain activity), and [5] behavioral (e.g., embodied, virtual). But they also noted a strange and alarming possibility:

“It is important to note that the observations in this computational study point at minimal guidelines and undoubtedly would fail to identify alternate forms of sentience.”