In countries where manhood must be proven, men have shorter lives

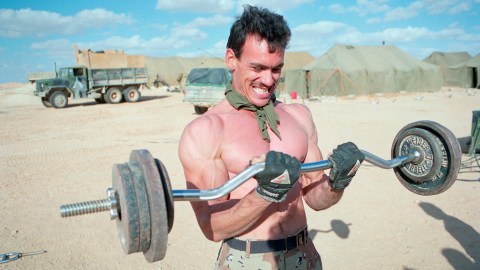

- Manhood is often viewed as “precarious” — unlike womanhood, it must be earned and defended. This can be done by engaging in risky behaviors, which showcase toughness and courage.

- In a new study, researchers found that in countries with higher levels of these beliefs, men were more likely to undertake risky behaviors and suffer from risk-related health outcomes.

- Most strikingly, the researchers also found that men live 6.7 fewer years in countries where precarious manhood beliefs are prevalent than in countries where they are rare.

Stereotypes of manhood link it with strength, aggression, toughness, and courage. Moreover, manhood is often viewed as “precarious” — unlike womanhood, it must be earned and defended. Thus, one way men can protect their masculinity is by engaging in risky behaviors like fighting, binge drinking, or fast driving. (Male readers might themselves recall something stupid they did to “prove their manhood.”)

Given that studies have repeatedly shown men to undertake more risky behaviors and to have shorter lives than women, a team of psychologists explored whether societal beliefs in precarious manhood might play a role in those differences. Their results were published in the journal Psychology of Men & Masculinities.

“Countries that view manhood as more precarious likely exert more pressure on men to uphold male role norms… via regular risk-taking activities, pursuit of risky occupations, and lower rates of preventive and health-promoting behaviors,” the researchers wrote.

A man by any other name

First author, Joseph Vandello, a professor of psychology at the University of South Florida who originally introduced the concept of precarious manhood 15 years ago, and his colleagues surveyed 33,417 college students in 62 different countries on their gender beliefs and attitudes. Included were four items intended to gauge the students’ precarious manhood beliefs. These were statements with which participants could indicate their level of agreement: (1) “Other people often question whether a man is a ‘real man.'” (2) “Some boys do not become men no matter how old they get.” (3) “It is fairly easy for a man to lose his status as a man” (4) “Manhood is not assured — it can be lost.”

With this data, they calculated the level of precarious manhood beliefs for each of the 62 countries. Countries with the highest levels were Albania, Iran, Kosovo, Nigeria, and Ukraine. Countries with the lowest levels were Finland, Spain, Germany, Sweden, and Switzerland.

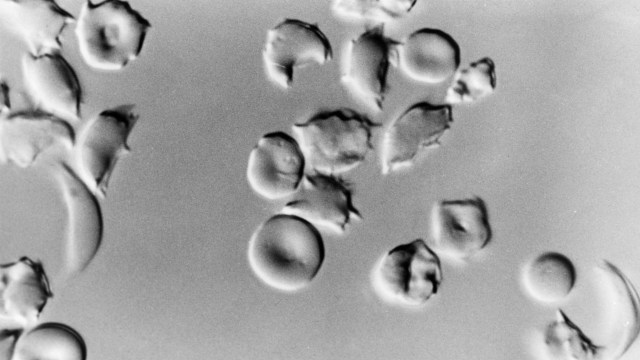

They then looked to see how country-wide precarious manhood beliefs were associated with risk-taking behavior (like smoking and drinking) and risk-related health outcomes (such as drowning, transportation accidents, and COVID infections). They found that men in countries with more prevalent precarious manhood beliefs were moderately more likely to engage in risky behaviors and to suffer from risk-related health outcomes.

Hold my beer and watch this

Considering that precarious manhood beliefs were linked to greater risk-taking and worse risk-related health outcomes, the researchers wondered if precarious manhood beliefs might also correlate with reduced male life expectancy. They were surprised to discover a striking association. In countries high in precarious manhood beliefs (one standard deviation above the average), men lived 6.7 fewer years compared to men in countries low in precarious manhood beliefs (one standard deviation below average). The result held even when controlling for potential confounding variables such as human development and availability of physicians.

“This finding is perhaps the most exciting and powerful to emerge from this study,” the researchers commented. “Country-level endorsement of the belief that manhood is ‘hard won and easily lost’ uniquely and strongly predicts how long men in that country will live.”

The study’s reliance on data exclusively from college students is potentially worrisome, as college students are generally unrepresentative of the broader population of most nations. Still, the study’s findings are seductive, as they make intuitive sense given common stereotypes about manhood. The survey’s size and breadth across dozens of countries is also impressive.

“While past research has linked masculinity to health, this is the first study, and the largest in scale, to show that a basic belief about the nature of manhood may have far-reaching implications for men around the world,” the researchers concluded.