Study: Taking Risks May Be Helping Teens Learn Better

Teens are not known to always make the best choices. They are ruled by the insecurities and passions of adolescence. They generally do not plan much for the future, instead living in the moment. But their behaviors, which may often be upsetting to their parents, might have a serious biological purpose, according to scientists. Opting for quick rewards and excitements, while taking unnecessary risks, might be a way for their brains to learn.

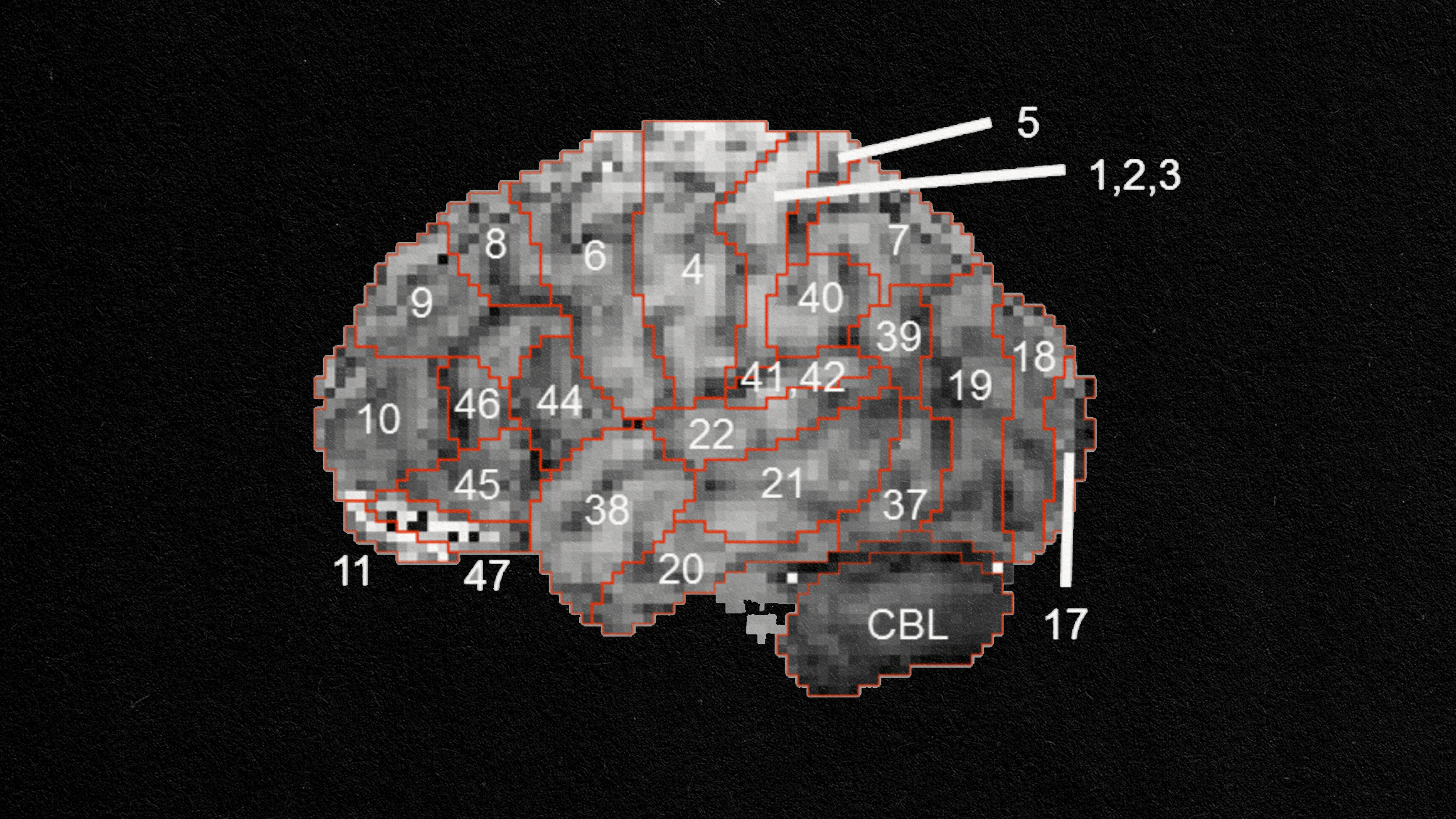

A new study published in the journal “Neuron” utilized an fMRI scanner to examine the brain activity of a group of 41 teens and 31 adults. Their focus was on the striatum, a part of the brain shown to be very active in teens seeking rewards or pleasures, as well as learning from such experiences. They also studied the activity in the hippocampus, the brain structure associated with memory.

The researchers had their subjects play a guessing game, which rewarded players for correct answers. Teens who wanted rewards beat the game faster than adults. Interestingly, striatum activity was similar in both adults and teens during the game. What was different is the role of the hippocampus in the teens.

“In neuroscience, we tend to think that if healthy brains act in a certain way, there should be a reason for it,” explains Juliet Davidow,lead author of the study and postdoctoral researcher at Harvard University in the Affective Neuroscience and Development Lab.

The role of the hippocampus was further evidenced by another test, where subjects performed a memory test to recall random flashing pictures that flashed on their screens during the game.

If the picture was linked to getting the right answer, teens were more likely to remember it than adults, showing that their episodic memory was engaged during reward-seeking.

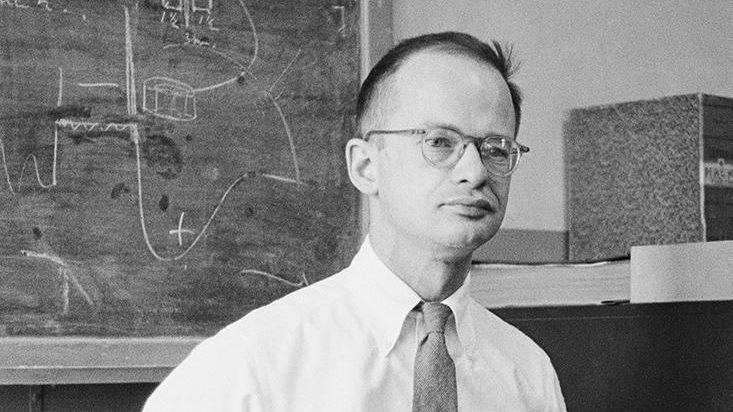

“If you’re someone who focuses on learning and memory, like we do in my lab, then you don’t think of reward-seeking as necessarily a bad thing. You think of rewards as something that shapes — and can have a really important role in shaping — learning,” said Daphna Shohamy, a cognitive neuroscientist from Columbia University, who was also involved in the study.

Next for the scientists is figuring out whether the hippocampus and striatum work together in other age groups.