Why flu vaccines only last a year

Photo: Numstocker / Shutterstock

- Researchers at Emory Vaccine Center looked at bone marrow to better understand antibody production.

- Due to constant mutations, identifying a “universal vaccine” has been challenging.

- The team found that blood markers are reliable indicators of what’s occurring inside of bone marrow.

We’ve known that this fall might present serious problems. Now experts are warning of a twindemic: the potential for a bad flu season combined with the ongoing coronavirus pandemic.

It all comes down to preparation.

The good news: countries in the Southern Hemisphere, including Australia and Argentina, experienced exceptionally low flu rates this year. That’s in large part due to COVID-19 restrictions. Measures designed to halt the novel coronavirus also slowed the spread of the flu.

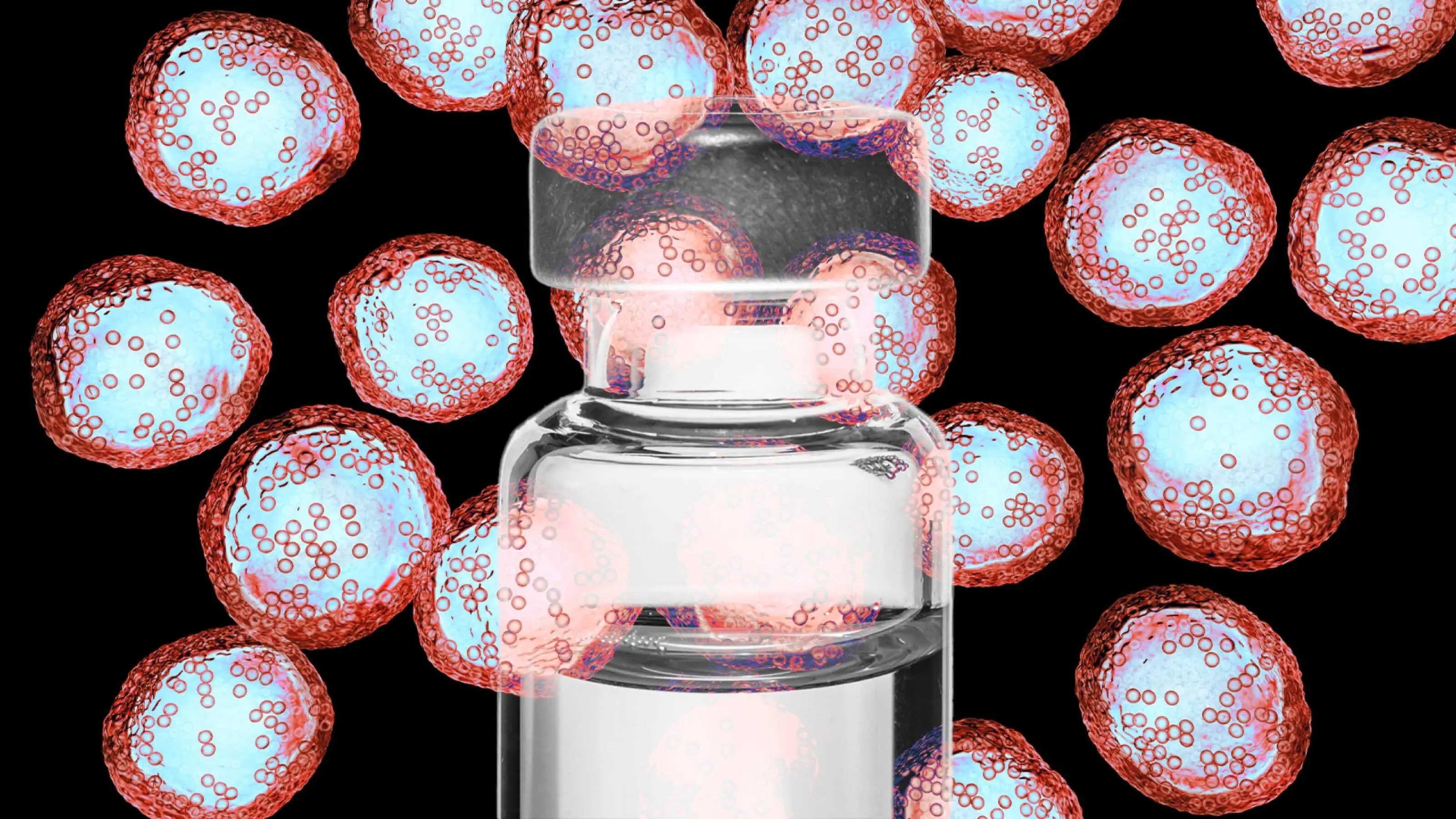

To curb the potential for a twindemic, American health officials suggest getting a flu shot as soon as possible.

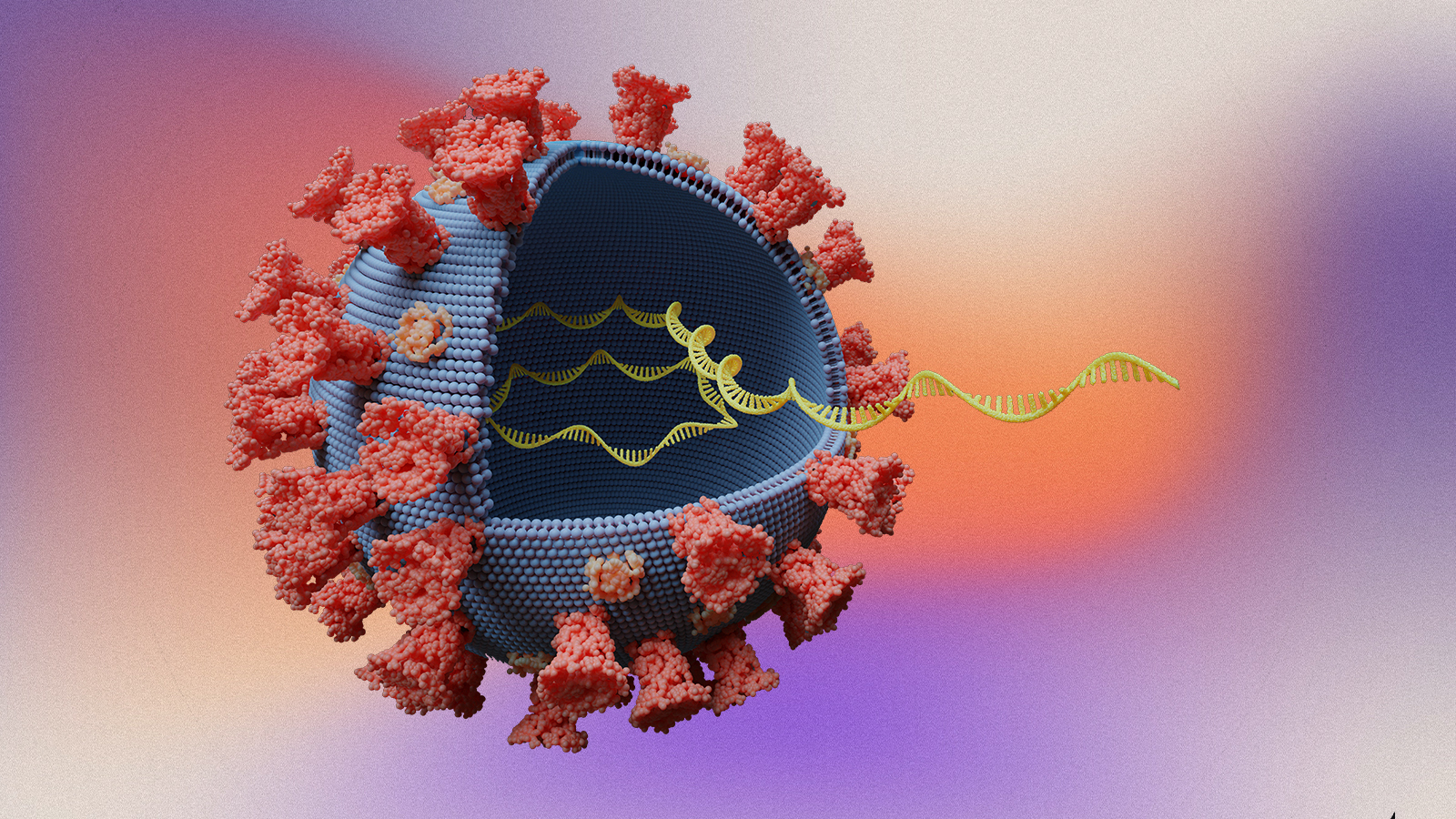

Vaccine science is tricky. While hope grows for a COVID-19 vaccine given the sheer number of researchers working toward one, flu vaccines present their own challenges, as a recent report from Emory Vaccine Center details.

There is no such thing as a flu—there are many strains of influenza. Whereas a number of childhood vaccinations inoculate us for a lifetime, flu vaccines only last for roughly one year, as the report in Science details.

This is largely due to mutations. Humans swap influenza viruses with birds and pigs. The viruses change midstream. Some strains are nearly benign. Others prove exceptionally lethal.

Every year, a flu vaccine is produced to combat three to four flu viruses in circulation. Some years are more successful than others. Influenza vaccines always require guesswork: flu viruses can change in the course of one season in a process known as antigenic drift.

Antibody-producing immune cells live in bone marrow, yet antibodies are usually tested for in the blood. For this research, Emory Vaccine Center director Rafi Ahmed looked at bone marrow samples—a more invasive procedure, yet one that yields clearer results.

Why vaccines are absolutely necessary | Larry Brilliant | Big Thinkwww.youtube.com

Everyone is equipped with antibody-secreting immune cells. The team at Emory first had to tease out these natural cells from antibodies produced by vaccination. Using sequencing techniques, they were able to identify endogenous antibodies.

As first author of the paper, Carl Davis, says:

“We could see that these new antibodies expanded in the bone marrow one month after vaccination and then contracted after one year. On the other hand, antibodies against influenza that were in the bone marrow before the vaccine was given stayed at a constant level over one year.”

Entering bone marrow is simply not enough for antibodies to continue to work. They need to root there. For the 53 healthy volunteers included in this study, traditional seasonal vaccinations could not provide this type of protection. After one year, between 70-99 percent of the antibody-producing cells were gone.

All hope is not lost. Researchers working on next-generation or universal vaccines should be encouraged that certain adjuvants could bestow longer immunity. The study also shows that screening for antibodies in blood correlates with antibody activity in bone marrow, which means future researchers can more easily identify candidates for trials.

Given increasing virus mutation due to climate change, a forever flu vaccine is going to take some work. Until then, it will remain guesswork. In a year in which a devastating twindemic hovers on the horizon, we should hope public health officials guess well.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter, Facebook and Substack. His next book is “Hero’s Dose: The Case For Psychedelics in Ritual and Therapy.”