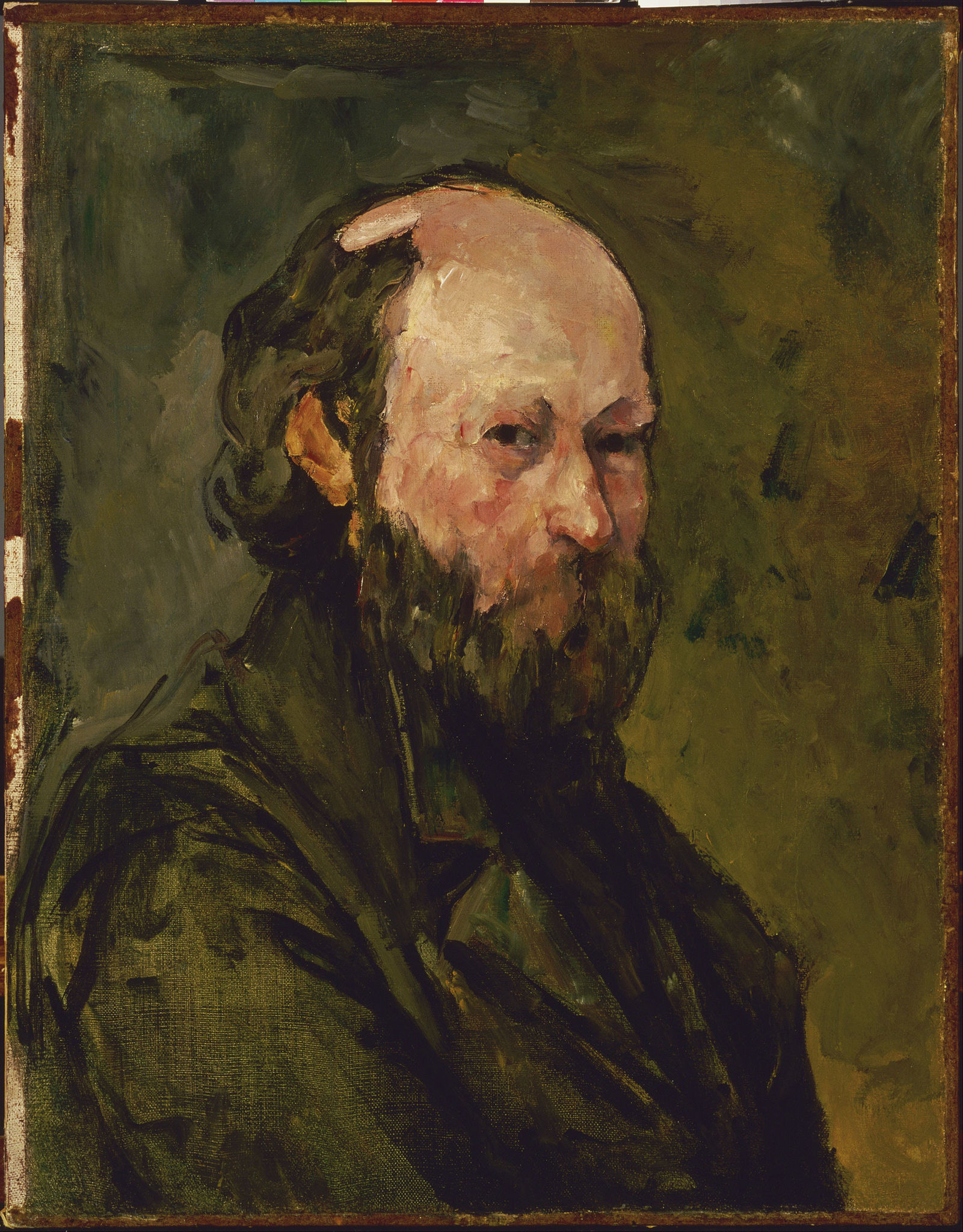

Did Paul Cézanne hide an early self-portrait underneath a 160-year-old still life?

- A conservator at the Cincinnati Art Museum found an unfinished figure hidden underneath a still life by Paul Cézanne.

- The museum considers the possibility that this figure might be one of the artist’s first, albeit unfinished, self-portraits.

- Further investigation will be necessary to determine the provenance of the portrait.

Thanks to advances in conservation technology, museum workers are constantly discovering new things about old paintings. Last year, an art gallery in Germany learned that Johannes Vermeer once intended to hang a painting on the wall in the background of Girl Reading a Letter in an Open Window. And this year, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam used state-of-the-art fluorescence imaging techniques to decide whether an unfinished oil sketch from Museum Bredius was created by Rembrandt van Rijn.

Another exciting investigation is currently unfolding in the U.S. Earlier this month, Serena Urry, a conservator at the Cincinnati Art Museum, noticed suspicious cracks on the surface of one of the institution’s most cherished possessions: Paul Cézanne’s Still Life with Bread and Eggs. What alarmed Urry wasn’t the cracks themselves — all old paintings show at least some signs of damage — but the fact that they seemed to expose hints of white pigment that felt out of place in the dark palette that Cézanne was known to have used during this time of his life.

Unlike the Rijksmuseum, the Cincinnati Art Museum does not have an X-ray machine on site, so they had to borrow one from a local medical company. Just as Urry had expected, scans revealed large amounts of white pigment hidden underneath the still life. At first, it appeared as though these preliminary brush strokes were applied in a haphazard and incoherent manner; it wasn’t until Urry flipped the image on Photoshop that the strokes assumed the likeness of a man — a man with two small eyes, a steadily receding hairline, and broad, stocky shoulders.

Who could this mysterious figure possibly be? Urry believes it is none other than Cézanne himself. “I think everyone’s opinion is that it’s a self-portrait,” she recently told CNN, pointing out that the figure is depicted in the way painters often pose for their own portraits, with their bodies turned to the side. “If it were a portrait of someone other than himself,” she adds, “it would probably be full frontal.”

Cézanne painted numerous self-portraits, but the vast majority were produced long after Still Life with Bread and Eggs. This would make Urry’s hidden portrait one of the earliest known depictions of the artist. But how can we tell if her assumption is correct?

When Paul Cézanne went bald

Before we try to answer this question, some background information is needed. Paul Cézanne was born on January 19, 1839, in Aix-en-Provence, a town in the south of France. The son of a successful banker, he traded the family business for pigments and paint brushes. An idiosyncratic artist in an age of short-lived art movements, Cézanne’s desire to combine representation with abstraction and personal expression serves as a bridge between 19th century Impressionism and early 20th century Cubism. Many art historians argue that Cézanne played a leading role in the development of modern art, while Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso are believed to have referred to him as “the father of us all.” He is, in short, a very important guy.

The unfinished figure underneath Still Life with Bread and Eggs, which was painted in 1865, bears some similarity to Cézanne’s earliest known self-portrait, dating from 1862 to 1864. Both images are painted with muted colors, in a realist style indebted to both the Spanish and Flemish Baroque. Both portraits also have an awkward quality to them, a sign that Cézanne was still coming into his own as a revolutionary painter when he created these images.

The figure beneath Still Life with Bread and Eggs certainly features Cézanne’s single most recognizable characteristic: his bald head. Unfortunately, it’s hard to say whether the painter had already started balding when he painted the hidden portrait. In the 1862-1864 portrait, Cézanne depicts himself with a full head of hair. Could he have lost it all in so short a time?

It’s possible. Lucien Pissarro, the son of Cézanne’s close friend and creative partner Camille Pissarro, remembers a hairless artist painting alongside his father outside of Paris in 1872, only a few years after the completing of the still life. This artist, Lucien writes, wore “a visored cap, with long black hair straggling down his back, yet bald in front.” Cézanne’s “large black eyes,” which “rolled in their sockets at the least excitement,” can arguably be recognized in the hidden portrait as well, although this may just be because it is unfinished.

Future research

While the identity of the hidden portrait remains a mystery, so too does its origin. Perhaps it was a failed painting that Cézanne never bothered to finish. Perhaps he reused the old canvas for his still life in order to save money. Talking to CNN, Urry considers the possibility that he suddenly became inspired and “needed a canvas” then and there to realize his vision. Considering the painter did not make much of an effort to remove the initial portrait, she might be on to something.

The Cincinnati Art Museum finds itself at the beginning of an exciting but lengthy process. Peter Jonathan Bell, the museum’s curator of European painting, sculpture, and drawing, says their next step will be collaborating with Cézanne experts across the globe. Multispectral imaging — used by the Rijksmuseum to investigate the Museum Bredius oil sketch — can be used to detect pigments and brushwork that are indiscernible to the naked eye, giving conservators a better understanding of how the hidden portrait was made and how it was covered up.