Fyodor Dostoevsky’s greatest critic explains why everyone should read his books

- Literary critics play an important role in keeping the legacy of authors alive and well.

- In his book, The Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, the Russian critic Mikhail Bakhtin makes a compelling case for why we should continue to read the long-dead writer.

- By endowing his characters with autonomy and dissolving social norms, Dostoevsky revealed truths about the world that would have otherwise remained buried.

Many Russian writers owe at least part of their success to the literary scholars that first discovered them. In the 19th century, praise from the editor Vissarion Belinsky could turn an inexperienced hobbyist into an overnight bestseller. Such was the case with Fyodor Dostoevsky, whose debut novella Poor Folk Belinsky declared required reading in his enthusiastic review of it.

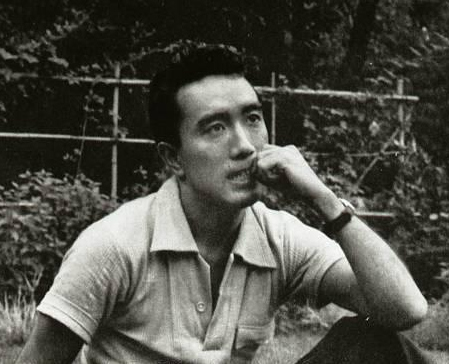

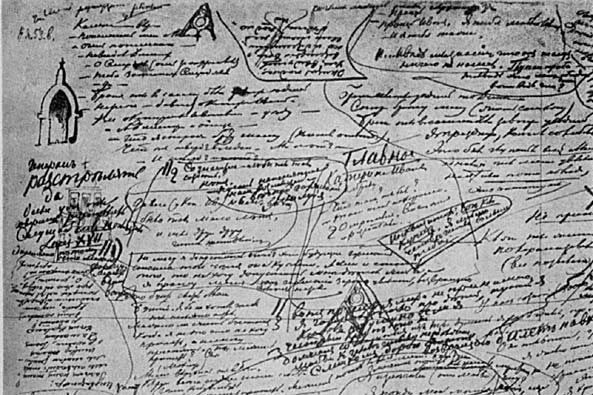

What Belinsky was for the 19th century, the literary critic and theorist Mikhail Bakhtin represented to the 20th. Born in czarist Russia in 1895 as the heir of a noble family, Bakhtin bore witness to the Russian Revolution and subsequent Bolshevik uprising. A prodigious writer and an even more prodigious smoker, he burned up his own, uncopied manuscripts when World War II caused a shortage in the supply of rolling papers.

Despite this act of self-sabotage, Bakhtin’s legacy survived. The critic approached criticism the same way writers approached writing. What interested him most about literature wasn’t its form but content; through fiction, authors could get closer to truth than they could through the reality that had originally inspired them. The more convincing the ideas presented in a novel, the more attention that novel ought to receive.

Over the course of his career, Bakhtin revolutionized our understanding of renowned authors, notably Belinsky’s champion, Dostoevsky. His deceptively named book, The Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, provides one of the most convincing arguments for why his writing was unlike anything that was published before or — indeed — has been published since.

Polyphony versus monophony

In spite of their job title, literary critics are hardly concerned with pointing out the flaws of a specific text. On the academic level, they are instead concerned with elucidating the otherwise elusive genius of the writers they study. Bakhtin says as much in the introduction of his Problems, where he promises to show, through “theoretical literary analysis,” how Dostoevsky’s fiction created a new way of looking at the world.

In short, Bakhtin argued that Dostoevsky wrote polyphonically or with multiple voices. Where other writers, like his contemporary Leo Tolstoy, used characters as thinly veiled mouthpieces to discuss their own ideas, Dostoevsky treated his fictional creations as though they were completely independent of him, driven by thoughts and feelings that were entirely their own.

To write in this way, thoroughly involved with the fictional world yet fundamentally disconnected from it, requires tremendous amounts of emotional maturity. This polyphonic style, Bakhtin goes on to say, hadn’t been seen since the death of William Shakespeare who, the critic argued, was able to reinvent himself with every play and, as such, created an opus in which each work was philosophically and ideologically distinct from the last.

The advantages of polyphony (as opposed to monophony) are numerous, but perhaps its single greatest boon is that it most closely simulates the way ideas are exchanged in the real world. When you read a conflict in a Tolstoy novel, you find Tolstoy arguing against a strawman. Dostoevsky’s conflicts, by contrast, are wholly dialogical: a fair and even matchup between two equally viable viewpoints.

The carnivalesque

If polyphony was Dostoevsky’s greatest strength as a writer, his aptitude for carnivalization would be a close second. This literary term is not nearly as straightforward as polyphony. Derived by Bakhtin from a lifelong study of Greco-Roman culture and its poetic arts, the concept of carnivalization requires a much lengthier explanation which the critic patiently provides.

Put simply, carnivalesque stories are like carnivals. During these ancient events, traditional norms were temporarily dissolved to make way for unrestrained festivity. Dressed in costumes or hidden behind masks, people from various social standings interact with each other on an equal footing. This coordinated chaos, in turn, awakens powerful emotions that allow individuals from different walks of life to establish authentic relationships.

The fact that Dostoevsky’s work is often described as a circus or madhouse indicates that Bakhtin isn’t far off in his assessment. In the author’s greatest works, nobles eat at the same table as beggars. The purest emotions frequently interact with heinous thoughts. In The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky attempts to show the goodness of God via telling the story of some of humanity’s vilest specimens.

“Carnival,” writes Bakhtin, “is past millennia’s way of sensing the world as one great communal performance.” By “bringing the world maximally close to a person and bringing one person maximally close to another,” these festivities can shield humanity from the kind of absolutist worldview Dostoevsky deemed to be the root of injustice and human suffering.

The problem with the problems of Dostoevsky’s poetics

Perhaps more than any other text, Bakhtin’s Problems revitalized the study of Dostoevsky in both Russia and abroad. On top of that, his theories on polyphony, the carnivalesque, and the historical significance of the novel as a uniquely 19th century artform frequently appear in the syllabi of critical theory and comparative courses.

But while Bakhtin’s interpretation of his country’s literary canon has received plenty of praise, it has not proved infallible to external criticism of its own. Discovering holes in the great critic’s personal worldview, articles written by his students add to the still ongoing dialogue, offering fresh methods through which to study literature’s masterpieces.

Bakhtin’s interpretation of Dostoevsky was called into question by Isaiah Berlin who, in his essay The Hedgehog and the Fox, argued the supposedly polyphonic author was characterized by his unwavering belief system. Where the uncertain and inquisitive Tolstoy abandoned one worldview for another, Dostoevsky — at least after his release from prison — remained a devout Christian until death; his religious sentiment colored every one of his novels.

This contradicting yet equally compelling argument does not imply that Bakhtin was wrong. Instead, it is simply a testament to the enduring genius of Dostoevsky. As history unfolds and society takes on different forms, aspects of old texts that have previously gone unnoticed suddenly become visible to the reader. Thus, people like Bakhtin play an instrumental role in keeping the legacy of people like Dostoevsky alive.